I BELONG to the last generation of mall rat. My experiences at the Lloyd Center Mall as a kid transcended commerce—it was where I had my first brushes with counterculture, whether it was the first CD I ever picked out that could tenuously be considered "punk" (Weezer's The Green Album), or the first pair of skate shoes I bought (even though I never skated). The mall was a place where you met up, killed time, and talked shit.

Now it's one of the only places I can go in Portland where I know I won't run into anyone.

Directly to the south of Irvington is the Lloyd District, a commercial area in an aesthetic stasis. It's home to central Portland's most impressive strip of fast food restaurants. Despite the fact that the area borders one of the city's most affluent residential neighborhoods, Lloyd institutions like Cadillac Café, Taste Tickler, and Helen Bernhard Bakery hark back to an era when Northeast was still uncool. The heart of the district is the Lloyd Center—the city's oldest urban shopping mall. Though hardly a tourist destination, Lloyd Center is a uniquely inviolable local landmark to Portlanders who grew up in the inner city—and it's currently going through some big changes.

A VISION OF THE FUTURE

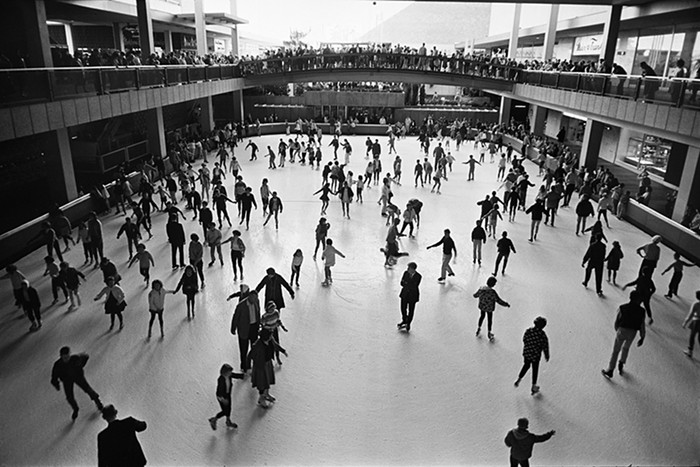

Conceived in the early 1920s by oil magnate Ralph B. Lloyd as a self-contained community replete with housing, businesses, and a 24-story hotel, the Lloyd Center didn't become a reality until 1960, seven years after Lloyd's death. While the mall may not have lived up to Lloyd's original vision, it was nonetheless considered a marvel of post-war ingenuity. Lloyd Center was referred to as a "consumer cornucopia" by Time magazine, and Oregonians touted the 100-store mall as the largest retail shopping center in the country at that time. The Lloyd has nearly 200 stores now.

In the summer of 2014, Lloyd Center announced it would be undergoing $50 million in renovations under new owners Cypress Equities—its largest overhaul since the shopping center was converted from an open-air mall to an enclosed space in 1989. Early 2015 saw the closures of Lloyd Center's Regal-operated indoor movie theater and Nordstrom—its last remaining original department store—and on December 31, 2015, Billy Heartbeats, a '50s-style diner and the mall's only bona fide restaurant, announced it would be closing its doors, too.

Bob Dye, the general manager at Lloyd Center, isn't fazed by the skepticism. He spends the majority of our phone conversation breaking down the renovations in rehearsed, geometric detail: the new pedestrian entrance on NE Multnomah, the complete interior redesign, the return of the spiral staircase, the huge increase in resource efficiency, and the upgraded ice rink (a contentious topic in and of itself—ice skaters who routinely use the Lloyd rink for practice bemoan the fact that it's being downsized, although Dye insists that it's merely being "reshaped").

But that doesn't change the fact that the present-day Lloyd Center is noticeably less lively than it once was, even on the weekends or around holidays, which partially speaks to the obsolescence of the "shopping mall" in general. (Joan Didion suggests that the mall is outdated in her famous essay "On the Mall"—and that was in 1975.) It's also far from the biggest mall in America. In fact, it isn't even in the top 20.

VACANT ON PURPOSE

Cyndee Kurahara—owner of Joe Brown's Carmel Corn, a Portland staple and the oldest storefront in Lloyd Center—is optimistic about what the renovations might bring, but notes that, so far, they've only had a negative impact on her business.

"I'd say it's a little slower, though it's starting to pick up now that people realize it's still open," she says. Yet thinking the mall might be closed is a reasonable mistake: In addition to the actual closures, the mall interior has been subject to nonstop construction since the renovations first started, creating an uninviting atmosphere for a clientele that already appeared to be ebbing. Vacant storefronts seem as common as cultural specters like Suncoast and Spencer's. A barricade now surrounds the center of the mall, where the ice rink is under construction. The barricade is covered with posters advertising the renovations. "Lloyd Center is modernizing history... Baby, it's gonna be awesome!!!" reads one of the ads. Neil Diamond plays somnolently from the overhead speakers.

Dye says that a certain percentage of the vacant storefronts are empty on purpose. "You have some spaces that have sat vacant intentionally because they were right in the crosshairs of the renovation—they've [stayed that way] to facilitate the renovation work," he says.

But when I ask Dye if he thinks the Lloyd Center will be able to attract new tenants that parallel the mall's architectural makeover, I'm given the runaround: "Whenever you have a newer, better product, you can attract newer, better customers, or in our case, tenants, and there's currently strong interest in the [Lloyd Center]."

In spite of the approaching completion deadline, nobody really seems sure who these "newer, better" tenants are. And according to the mall's owners at Cypress Equities, it sounds like they might not even exist yet.

"The developer won't share information about who they're speaking to until a lease is officially signed, because otherwise it can damage negotiations," says Glenn Miller, the portfolio marketing director at Cypress Equities.

"If someone is pleading the fifth with this kind of thing, you kind of assume they're guilty," says Katrina Scotto di Carlo.

Scotto di Carlo and her husband Michael are local economy experts and the founders of Supportland—a network of independent restaurants and retailers that employ a shared points system (sort of like a universal punch card) that provides an incentive for supporting local businesses.

"Retail is changing rapidly and the sort of discount shopper that [might have gone to the mall] is just going online," says Scotto di Carlo. "The reason people engage with retailers now isn't just because they want a product, it's because they want to engage with a sense of place and their community."

In its nascence, online shopping was an augmentation of brick-and-mortar retail—but now it's the norm, placing malls like Lloyd Center in the unfortunate blind spot between independent boutiques and more upscale shopping centers.

In April, the Wall Street Journal reported that a variety of prominent chains are slowly withdrawing from weaker malls—and it isn't hard to imagine Lloyd Center making that list.

"We're kind of in this transitional period, but I think that the market footprint of big box stores and malls is going to be vacated at a higher and higher level as we approach this new equilibrium between online retail and [independent retail]," says Scotto di Carlo. "I don't know if the old investors have given up completely, but I really don't see how the target market is still going to be there for Lloyd Center."

Scotto di Carlo also suggests that smaller businesses generally steer clear of spaces like the Lloyd Center, because they violate the values of independent retail by design.

"What malls did is they said, 'Let's zero out sense of place and let's build a wall around our environment,' and that was attractive initially to customers, but nowadays people are really yearning for a sense of place."

Despite her doubts, Scotto di Carlo still thinks the mall has the ability to succeed in "New Portland"—but only if it's interested in fostering this sense of place.

"I think it's a really big challenge, but it can be done," she says. "The Lloyd Center has two really big advantages—the ice rink and the fact you can walk around with your kid in a stroller and not get rained on—and if they maintain those and add a sense of place to the puzzle, I think [it could work]."

YES, BUT DO THE KIDS GIVE A SHIT?

Mere blocks from the Lloyd Center is the upstart Hassalo on Eighth project—the sort of reurbanizing condo leviathan that native Portlanders have grown to despise. In addition to housing, the insular suburb will boast new branches of quintessential Portland anti-chains like Little Big Burger and Green Zebra Grocery. The developer's mission statement claims they intend to transform "the Lloyd District from a vast parking lot into a vibrant, eco-friendly, 24-hour community just minutes from downtown." And while that reads like pamphlet pablum, there's something to be said for the underlying narrative. Hassalo on Eighth's decidedly modern flair only accentuates the neighboring Lloyd Center's anachronistic qualities, renovations be damned. It's the suburban Eden of Ralph B. Lloyd's dreams—even if it's problematic for other reasons.

"The Lloyd District has changed a lot over the years, and the Hassalo on Eighth project really is the centerpiece," says Peter Koehler, the director of business development at Green Zebra. "We purposefully call it a neighborhood and not a district because it has changed from car-centric and business-centric to a really thriving mix of residents, businesses, pedestrians, bikers, cars, and light rail—this is a different Lloyd than the one you grew up with."

The barometer of cultural relevance is—and will always be—whether or not kids give a shit about you. I ask Lloyd Center's Dye if he thinks that "the mall" is still a popular pastime among youth.

"Every person who walks into this center, as far as I'm concerned, is a potential customer," says Dye. "The kids spend a lot of money here—they hang out here, they walk up and down, they do the same things kids did 20 years ago, and 30 years ago, and 40 years ago."

Maybe I'm just not going on the right day.