THE SALIENT FACTS about Sarah Kane's 4.48 Psychosis are as follows: Kane was a young playwright with a history of depression when she wrote the play, a nearly formless script—with no stage directions or character attributions—that centers on a mental patient's depression and suicidal impulses. Shortly after finishing the play, Kane hung herself, making it basically impossible for future audiences to separate Psychosis from Kane's own biography.

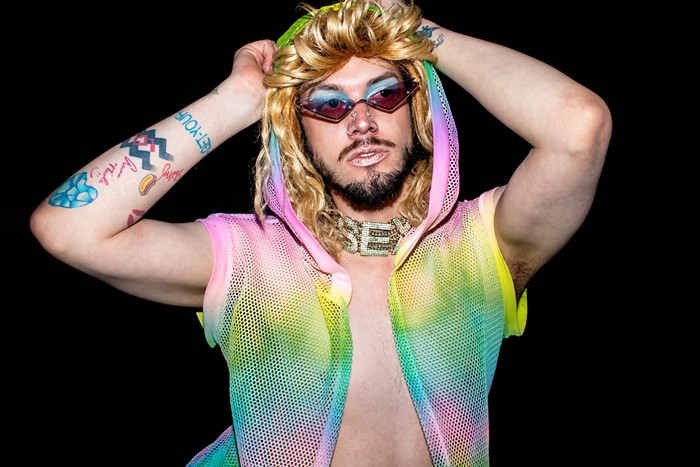

In choosing to perform Kane's final work, defunkt tasked themselves with carving a production out of the raw material provided by the script. They chose to cast Psychosis with three actors—two men, Joel Harmon and Matthew Kern, and one woman, Christy Bigelow. Bigelow acts as the script's central character, a mental patient, struggling with depression and suicidal impulses (see what I mean about separating the work from the life?). As she rails against herself, her doctor, and mortality itself, Bigelow brings poise, deadpan humor, and self-awareness to a production that is otherwise characterized by a lack of all three.

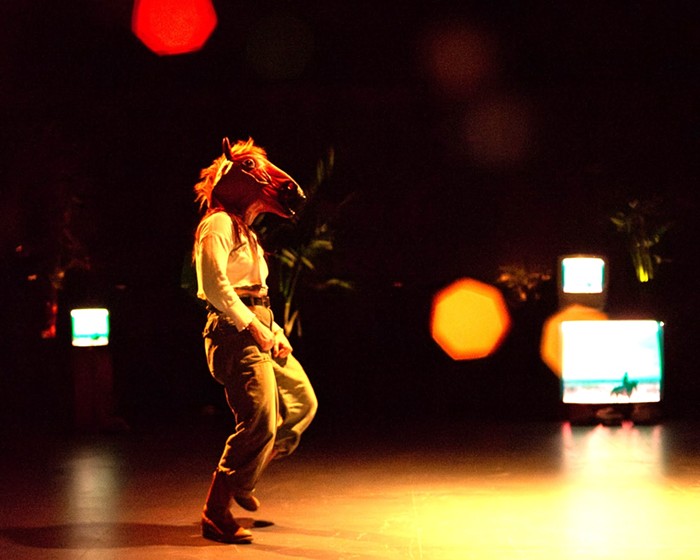

Harmon and Kern are supplemental figures, foils to Bigelow's pained introspection—but rather than clarifying and sharpening Bigelow's performance, the two men, under the none-too-lucid direction of Grace Carter, only obscure it. Carter favors movement that implies meaning without actually conveying any, and amid all the talking in unison and cryptically significant hand gestures, Harmon and Kern quickly bog down in self-seriousness. (I should confess to a deep bias against any production that opens on a silent actor making prolonged eye contact with the audience. In the grab bag of devices that mean something serious is happening right now, it's arguably the laziest.) The show's gaudy production design—costumes that look like yoga gear on the USS Enterprise, projected images of flowers, generic sound effects that connote "crazy"—only reinforces the impression that Carter & Co. are overwhelmed by their material.

The discomfiting thing about 4:48 Psychosis is that it documents a mind turned on itself—a fierce intelligence fighting a battle the mind can't win, some uneasy meeting of Artaud's theater of cruelty and Virginia Woolf at her most self-lacerating. Instead, defunkt gives us an avante-garde adaptation of Girl, Interrupted, a production that obscures the script's best qualities in aimless pseudo-depth.