WILD TALES has everything you could want from a rock autobiography. Graham Nash lays it all out plainly, from his years in the Hollies during the British Invasion's first crest, to the coke-addled, tumultuous, on-again-off-again partnership with David Crosby and Stephen Stills (and sometimes Neil Young). More than 50 years after the Hollies released their debut single, and 42 years since his first solo album—the under-looked gem Songs for Beginners—Nash is in the midst of his third-ever solo tour, which doubles as a book tour for the gossipy, eminently readable Wild Tales. (Nash also appears at Powell's [1005 W Burnside] at 4 pm on Sunday, November 10.)

MERCURY: Last weekend [October 23 and 24], Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young played for the first time in eight years performing at Neil Young's annual Bridge School Benefit. Are the four of you able to pick up your guitars and pick up where you left off?

GRAHAM NASH: It does seem that way. It did seem that way on Saturday and Sunday, I'll tell you. Something happens when the four of us play together, especially when we play acoustic. Because when you play acoustic, you're stripping the songs down to their very essence, and therefore a song has to be really great if you can move thousands and thousands of people with an acoustic guitar. The song has to be fabulous. And with all due respect, we have a lot of songs between us. It was just delightful to play with Neil again. And I think David and Stephen felt exactly the same way.

Why write a book now? Is this something you've been planning for many years?

No, not at all. It was a very spontaneous thing, as most things in my life are. I've lived in Hawaii for the last 35 years, and I had dinner at my house in Hawaii with a friend of mine who's a book agent. Her name is Jillian Manus, and obviously after dinner we're all talking and telling stories—she's telling stories about her life, I'm telling stories about my life, and she said, "You know, you should really consider doing this seriously." And then I began to realize that, you know, I have three great children. They're in their 30s now, and so they know who I am. They know how I deal with life. They know how I face my weaknesses and how I amplify my strengths. They know a lot about me. A year ago my firstborn son, Jackson, gave us a beautiful granddaughter. And I began to realize that, you know, I am 71 now, and with all due respect, I could drop dead in the middle of this conversation—which has happened to friends of mine. And so I thought that Stellar Joy, that's my granddaughter's name, I thought maybe she would want to know who her grandfather was, and what obstacles he overcame in life to get to where he is now. So I really did it for my children and my granddaughter. It wasn't a long process—it was nine months from conception to the book in the airport store.

Oh, wow. That is pretty speedy.

Yeah. Well, I've got to get on with my life. And that's one of the great things about finishing the book: I can now let it all go. And really, truly get on with the rest of my life, which will be equally magical, I'm sure.

Was putting these stories onto the page cathartic for you in a way that you might not have expected?

All of it. All of it was cathartic. I've never been a man to look backwards. I don't care what happened 40 years ago. There's nothing you can do about it. But being forced to look back at my life, I'll tell you something. I got to the end of the manuscript; I looked down at the pages and thought, "Good lord. I wish I was him." Because in recalling my life, it's been an incredible life, even though I'm living proof, this conversation, and the future, when I did look back at it all, it's been insanity [laughs]. And shows no sign of quitting, either.

So I understand that you spoke aloud most of the story, and Bob Spitz was the one to type it out?

Yeah. Jillian Manus suggested that I talk to him. He did that beautiful biography of the Beatles, so he'd already done all the research about what life was like after World War II in the north of England, and what 15-year-old kids got up to and stuff. So I didn't have to explain who I was—he knew who I was. We put a tape recorder between us, a little digital thing, and I just started talking. And Bob then took all the tapes and transcribed them and gave them back to me, and I put them in the correct order and checked the dates and all that stuff, and that was the process. Bob didn't even want his name on the book. It wasn't "written by Graham Nash and Bob Spitz." He said, "No, all I did was type your words."

Have you gotten feedback from anybody who might be mad about any of the stories in the book?

Yeah. Only one, really. And that was my description of Stephen's father as a "hustler." Stephen wasn't too happy about that, and I understand why, and I'll change it in the second printing. But whenever I've asked Stephen about his father, that's what he would tell me. You know, he was a bit of a hustler, he may have worked in the CIA in Central America, he may have done this, but he was kind of a hustler, so I said that. But it pissed him off. But that was the only thing, and that's not too much, really. I was really concerned about Crosby, because I was so fuckin' brutal about what he'd done to himself and his wife Jan—and to us, his friends. But David told me not to change a word. He was a man; he stood up to what he'd done. You know, he admitted that he was a little screwed up there.

Is this current tour also a book tour in a sense?

Yeah, my days off are the show days. On a normal day off, I'm doing photography shows and painting shows and signing books at bookstores. I've never been an artist to just put something out there and let it lie there and hope it sells. I want to do everything I can to give the publishers and the bookstores the tools that they need to sell plastic.

Are you taking the opportunity to tell some of these stories onstage, in between the songs?

I do. Yeah. And it's fascinating, you know. A lot of people, I'm finding out, are very interested in how songs that they love were written. You know, what instigated "Our House," for instance, or why did you write "Cathedral," or what's "Teach Your Children" about, really. And I talk about 'em. As a matter of fact, I had to ask my crew—I said, "Am I talking too much?" And they said, "No, no, no, no, no, it's in a way as important as the music."

What is the set of this current solo tour like?

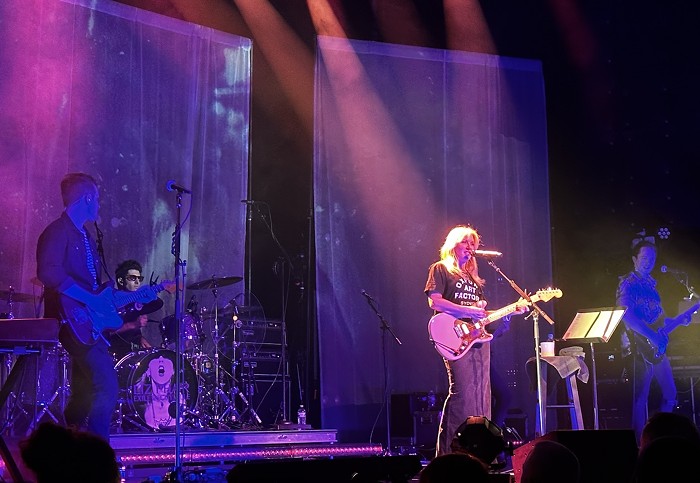

I'm playing with David's son James Raymond on keyboards and Shane Fontayne on guitar. And I'm playing anything I want. And it's a fantastic freedom. With a normal [CSNY] set, I have seven of my songs, seven of David's, seven of Stephen's, and seven of Neil's, and the show's over. I'm just coming to the end of finishing up the three- or four-CD box set of our stadium tour from 1974, the CSNY stadium tour. And our average show length was about 30 songs. We have hundreds of songs that we need to do. So in my show I'm doing stuff that I've never done before, I'm doing songs that I wrote this morning, I'm doing songs that they truly love and have loved for almost 50 years. I'm doing Hollies songs. I'm doing anything that I want, and it's a great freedom. "Wounded Bird." "Simple Man," which I haven't done for years. "Bus Stop," from the Hollies. "King Midas in Reverse." I can go anywhere I want, and I'm loving it.

You mentioned new material as well. Do you have new songs on this tour?

Absolutely. I have 28 new songs. So as soon as I'm finished and I have time after Christmas, I'm going back into the studio to make another solo record. Crosby has a solo record coming out in February. And the CSNY box set will be coming out on March 4.

Is that compiled from different dates from the 1974 tour, or is it all from one show?

No, no, we did 31 stadiums and recorded nine of them. So this box set is made from the nine multi-track recordings that we did. But like I said, each set was over three and a half hours. So you times that by nine, and that's a lot of music you've got to listen to, to make sure you didn't miss anything brilliant.

What were some of the undiscovered treasures you came across?

I just finished mixing a song that I found of Neil's that's probably the shortest Neil Young song in history. It's about a minute and 10 seconds, and it's called "Goodbye Dick." And it's about Richard Nixon and Rose Mary Woods.

Speaking of Nixon, the '60s and early '70s were such a political time in America. The same is true of the past decade or 12 years or so, but I don't think we got the kind of protest music that we got in the '60s and early '70s, at least not in the mainstream.

That is possible, but you have to realize two things: One, the younger bands are much more interested in prolonging their career, and don't want to make any waves. And I understand that completely—I was in a band like that with the Hollies. But on the other hand, you can count the people that own the world's media on two hands, and the last thing they want on their airwaves is anything that rocks the boat. The last thing they want on the airwaves is for the sheep to wake up. And you know, I don't like sleeping sheep.

Is there hope, then?

Of course there's hope. Of course there's hope! If there was no hope, I'd probably have offed myself years ago. There is tremendous hope. You have to look at things through the eyes of your children and your grandchildren. Of course there's hope. Is it a struggle? Of course. Is it difficult? Of course! Is it possible? Of course.

Many of your songs take very simple, basic ideas that are often very personal, but you convey them in such a way that they can be universal.

Because those ordinary moments happen to all of us. "Our House" is a perfect example. What an ordinary moment: I'm going to breakfast with Joan [Joni Mitchell] and on the way home we pass an antique store that she sees a vase in that she wants, and I persuade her to buy it. And it's a grisly day—I'm sure in Portland you know exactly what I'm talking about, kind of gray and drizzly and stuff, and as we're going through the front door I say, "You know what? Why don't I light a fire, and you put some flowers in the vase that you just bought today." What a fucking ordinary moment. But a tremendously profound moment. And I take as much care with the ordinary moments as I do with the profound moments.

Lou Reed died recently of a complication from a liver transplant, and it made me think of Crosby, who got one many years ago and is still doing well. And you seem to be in excellent health. Is there any secret to longevity?

I'm in pretty good health. Who knows what's going on inside this body? But I wake up feeling energetic and I wake up feeling incredibly optimistic about the future. I think the universe is out to love me and support me. I have never been one of those, you know, "How you doing?" "Well, I'm getting old and creaky." I've never been that guy. You ask me how I am? I'm fucking fantastic. Because I'm alive and I'm breathing. Let's start there, on a very basic level. And that's the attitude I've had all my life. I love being alive.

So there's no secret diet or magic vitamin or anything like that?

Not at all. No. I have to live my life with... Here's what's going on. I'm trying to be the best I can be at everything I do. I want to make the best cup of tea. I want to be the best father. I want to be the best musician, the best friend, the best husband. I'll never make it. But I'm trying.