Sat Jan 22

Dour Fir Lounge

830 E Burnside

Throughout the '90s, Royal Trux were a rock anomaly. Barely tethered to this green Earth by twin trash-punk junkies Neil Hagerty and Jennifer Herrema, the group swept up particles of mystic space rock, Stonesy twang, and cracked, guttural utterings across 10 static-deluged recordings. Broken blues riffs and delusional vocals slipped right off the rails or flared up and burned out with the lifespan of lighter flames. Royal Trux were a self-contained plane of droning scuz rock; the flickering pilot lights of Hagerty's jarring guitar psychosis and Herrema's craggy calls navigating listeners through endlessly meandering melodies. Most Trux recordings sounded like a gang of rural meth-lab musicians detoxing on peyote and recording the rustic happenings with cult-obsessive results.

Unfortunately, the Trux chapter in rock history closed right after the turn of the new century: The band's creative energy was short-circuited by the ongoing intrusion of drug addiction and the death of Herrema's father. Once bonded in both music and holy matrimony, Herrema and Hagerty are now charting individual, unconventional courses, splitting ownership of everything from their Virginia property to the letters of their old band name. That leaves Herrema with RTX, her second band in her 32 years, and Transmaniacon, the group's cosmic maiden recording voyage.

Speaking from her Sunset Beach, California home, Herrema says of RTX's debut, "It felt really linear as far as thinking about the sound and pushing it through to the end. With Neil, what made [Royal Trux] was the different sensibilities that we brought, and it was never entirely linear. RTX, from start to finish, is about getting it out in the way you see it in your head without having to pull off to the side."

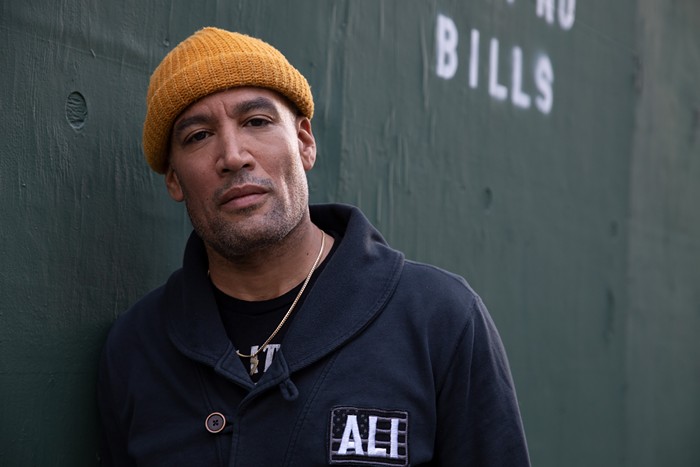

Herrema drawls out her answers like the surfer she's become. But she's less the hang-loose beach bum than, as one writer put it, a Harmony Korine hesher (accented by the platinum eyebrows and hair), with a low purring delivery. And on Transmaniacon, her throaty crackle snakes through a labyrinth of scrap rock and salvaged arena metal, a combination that's nearly as confounding and contradictory as any Trux output.

Her vocals are vocodorized and amplified, punctuating steroid-pumped instrumentation yet balancing those fist-waving experiments against a rough core that keeps Herrema more woman than machine. Even the murkiest sludge has a shine to its surface here, but there's still something basement-floor dirty and low-grade psychedelic inherent to the vibe--due to song titles like "Low Ass Mountain Song" and "Joint Chief" and Herrema's style of spitting out lyrics like she's loosening phlegm. Most importantly, in Herrema's permanently art-damaged world, "linear" is never going to mean straight lines.

Herrema created Transmaniacon--named, as she ambiguously explains, because "the alliteration of it sounded like the sound I wanted in the record"--with producer Nadav Eisenman and multi-instrumentalist Jaimo Welch, twenty-something music outsiders she met through a photo shoot.

"They didn't come from any musical scene or band," she explains. "There was just a real beauty and honesty and that's basically what enabled a whole new direct line of communication. Most musicians consciously or subconsciously have boundaries already formulated in their heads."

Over two years and three recording studios, the RTX trio created unusual methods of musical expression. "I wanted it to be a new communication," Herrema explains. "So basically [recording involved] a lot of nonmusical adjectives and drawings and physical gesturing to [cull] what I needed. I don't think [the record] would've been half as cool without it." More recently invited to that insular conversation are Paz Lenchantin (A Perfect Circle, Zwan), Brian McKinley, and Dave Brotherton, musicians Herrema says are permanent players in the RTX vision.

And for the off hours, there's also Herrema's ongoing visual artwork (part of Royal Trux' past aesthetic), which she seems to approach with the same methodology she applies to her music: "I just have big poster paper pinned to the wall and I can add to it incidentally," she explains. "You don't look at it every day, but after a while it takes on a life of its own."