The Devils

Portland Center Stage, 274-6588

Through Oct 22

"I just can't follow the story."

"Oh, I liked the part where he bit everyone."

Those were just two of comments overheard in the lobby during the first intermission for The Devils, the debut performance of Portland Center Stage's new artistic director Chris Coleman, at the Newmark Theater.

Though vast and beautiful, with an interesting set that made full use of the space, that was where the play was going on, which made the destination much less appetizing. The Devils is Elizabeth Egloff's adaptation of Dostoevsky's novel about Russian revolutionaries. Set in the Ukraine in 1870, the play focuses on the comical, then tragic conflicts among a group of dissidents, the upper class intellectuals who lead them, the regional politicians who try to contain them, and the secret police department that spies on them.

One can see why Chris Coleman thought of mounting this adaptation as his debut production. It's written by a supposedly hot young playwright, so it has the cachet of contemporaneity. It demands a large cast, which gives Coleman a chance to work with several of the city's regulars while conveying "bigness" to the audience. And Coleman did the show before, at his previous theatrical venue in Atlanta, so its familiarity makes things easier on him.

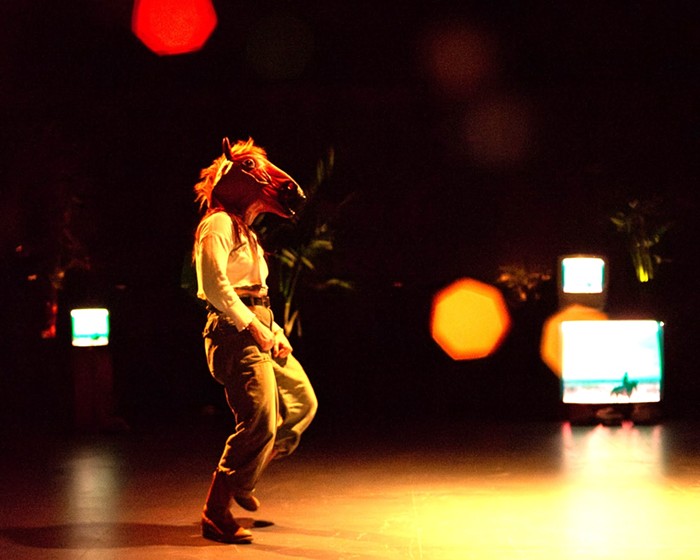

One wonders if the Atlanta version of the play was as boring and incomprehensible as this one. It's not just that the Russian names are unfamiliar to the audience (and the program even provides a helpful character guide in addition to the cast list). It's also that the relationships between and among characters are presented chaotically and sketchily. For a text of such breadth, the play feels both rushed and static at the same time, despite all the imposed excitement of physical brawls in stately rooms (that biting scene), and lots of running up and down stairs by the secret police. The play is already hard to follow, and the production just doesn't have a crisp, communicative feel. Information doesn't seem to extend far beyond the edge of the stage. Many of the characters are oddly passive, particularly the former leader of the revolutionaries, Nicholas Stavrogin (Atlanta import Michael Newcomer).

Troubled by something from the past he won't explain, Stavrogin, when not biting people's noses, lies in bed refusing to communicate with anyone. Other characters, such as the revolutionary cell's printer, have problems as well, but one would be hard-pressed to actually cite them after the show.

During the third portion of the play, the real drama was in the orchestra seats, where patrons valiantly sought to stay awake, often without success, as the production crawled to its three-hour mark. The play seems to be about the futility of attempting to change anything. Given the inauspicious nature of this debut, change--in the form of Coleman replacing the mediocre Elizabeth Huddle--may indeed be futile.