Classic Greek Theatre of Oregon's production of Euripides' Orestes moved indoors last weekend, taking up residence at the West End after a few weeks at Reed College's outdoor amphitheater. Orestes is a surprisingly fresh, clever piece; the clear vision of artistic director Keith Scales expertly steers the production on a sure course between melodrama and farce.

The show opens with Electra worrying over the body of her brother Orestes, who has fallen ill. Orestes and Electra recently orchestrated the murder of their mother, and now the guilt is driving Orestes mad. When he wakes up, he is eager to clear himself of the charge of matricide. Electra and Orestes seek the assistance of their uncle Menelaus—and when he refuses to help them, they (along with Orestes' best friend, Pylades) plot revenge against him.

I spent the first 10 minutes of Orestes considering whether I could in good conscience leave during intermission (reluctantly, I concluded that I could not). The set was unimaginatively functional, the lighting seemed to consist of a dimmer switch being slid hastily up and down, and some of the costumes had tassels. Electra moping over Orestes' twitching body wasn't exactly blowing my mind.

After a few minutes, though, something hit me: Orestes' twitching, Pylades' swaggering... this wasn't drama done wrong, this was comedy done right. The show is funny, and it's funny on purpose. But it's no mere farce: The sense of relief that comes with realizing that the production is perfectly aware of its ridiculousness also makes you trust it more during the serious scenes. It's a tricky balance, but the cast pulls it off.

Christy Bigelow does great work with Electra, painting her by turns passionate and sympathetic, and strident and self-righteous. It can be hard to see past Zachary Koval's twitch sometimes, but he does a solid job depicting the mercurial nature of mental illness—and when Orestes reveals a misogynistic streak in act two, Koval delivers his dismissive lines with a hilarious assurance.

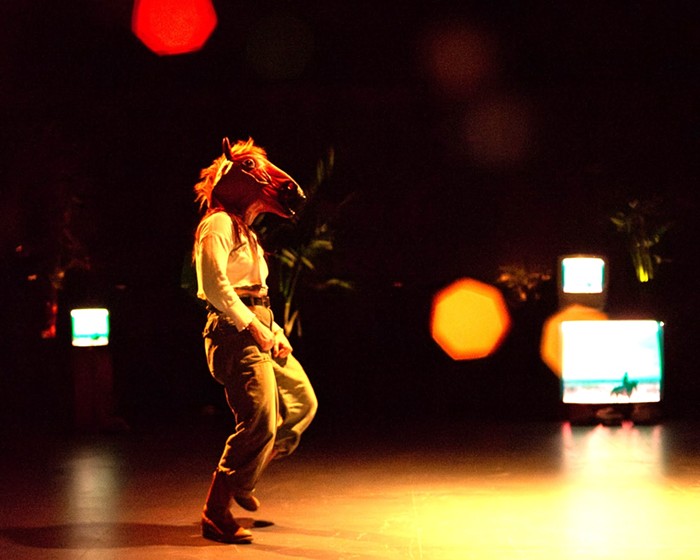

The group of handmaids who function as a chorus add a tremendous amount to the production; and if they sound at times like a lesbian folk collective, it's probably because local singer/songwriter Sarah Dougher wrote the music (sorry, I couldn't resist). Dougher's arrangements are by turns humorous and affecting, and when combined with Andrea Harmon's silly, dance-hall choreography, they solidify the chorus' effectiveness.

All told, I'm glad I didn't leave during intermission: I would've missed a production that ending up surprising me with its cheek and charm.