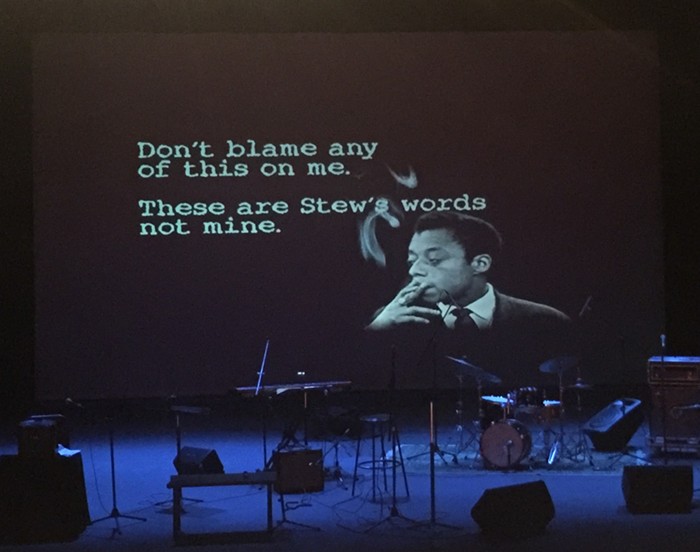

Notes of a Native Song, the ever-evolving stage show loosely connected to the life and career of writer/activist James Baldwin, is a purposefully messy affair. Even before the show started, singer/co-songwriter Mark Stewart (better known as Stew) was already onstage at PSU’s Lincoln Hall, acting as his own stagehand, leaving behind a wrinkled white sportscoat and a sheaf of well-loved papers. Before performing each song, he would pluck one of those sheets, revealing that each one was actually made up of a few smaller bits of paper, stuck together with bright red tape.

The music, too, was lovingly unkempt. The blues and psych-pop tunes written by Stew and his creative partner Heidi Rodewald (who played bass and sang backup) were stripped down and given some rough-hewn rhythm from a local drummer who'd been taught the songs earlier that day.

And though they’ve been performing this material all over the world, it still felt like they were finding their places within it, with Stew repeating phrases as if on the fly and tossing in little comments when some of his lyrical jokes didn’t land. When he sang about Al Gore’s head getting put in a “Miami vice” during his musical ode to the currently weather-beaten state of Florida, he flashed a note of surprise at not getting a reaction, before encouraging the audience to “ask the people next to you what that meant.”

The loose feel of the entire evening worked well with the material that Stew and Rodewald were presenting. There’s no throughline or narrative to this song cycle other than, as he mentioned at the start, Stew thumbing his nose at a neat and tidy “Black History Shortest-Month-of-the-Year”-type recitation of Baldwin’s achievements. A child of punk, he also seemed to be going out of his way to avoid the kind of polished production akin to Passing Strange, the semi-autobiographical musical that won him a Tony and brought him national acclaim.

While most of the crowd exploded in excited applause at the end of the show, a healthy chunk of them didn’t know what to make of Notes. They might have come in expecting a historical musical but were instead given songs wrestling with the murder of Trayvon Martin and the nasty legacy of racial injustice in the Sunshine State. And when he did he speak or sing of Baldwin, Stew was clearly interested less in the details and more in the big picture of what the writer/critic represented.

In an improvised rant, Stew marveled at the fact that Baldwin sought and received the guidance and encouragement of Native Son author Richard Wright, and then turned around and criticized the elder author’s work in the essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel.” Later, he sang of the hypocrisy of Malcolm X and Eldridge Cleaver dismissing Baldwin for being gay, saying that those two men likely engaged in homosexual acts when they were in prison.

As much as Stew clearly admired much of Baldwin’s writing, he didn’t use this song cycle to write a fan letter. During a segment where he sat off to the side, his voice fed into a modulator, he took on the guise of someone who insists that Stew loves Baldwin and all other black writers simply because they were also black, that criticism of other black artists' work is detrimental to their mutual advancement. It’s the kind of argument Baldwin would have scoffed at.

In that way, as flimsy as some of the connecting threads may have seemed on the surface, the show was a perfect a reflection of Baldwin’s mindset and aesthetic. The song about the death of Martin stung not only through Stew’s use of pieces of the transcript of George Zimmermann’s 911 call as lyrics, but gut-punching phrases like, “Black met brown that night/Black stayed black but brown turned white.” In a line like that, or the “hanging chads and lynching boys” lyric in his song about Florida, Stew slapped us awake to the civil rights violations that Baldwin fought so vehemently against some 60 years ago—and that are still a long way from being resolved.