For the past 11 years, City Commissioner Nick Fish's office on the second floor of Portland City Hall has been a reliable junction for lively policy discussions, thoughtful conversations between strangers, and nerdy government jokes. But on Friday, as the community reeled from Thursday's announcement of Fish's death, the lights in his office were off and the doors shuttered.

"It's a sad, sad day in City Hall," said Marshall Runkel, chief of staff for Commissioner Chloe Eudaly, whose office sits across the hall from Fish's. "It's a difficult feeling to explain."

Fish was diagnosed with abdominal cancer in 2017—a diagnosis that rarely got in the way of his steadfast commitment to his job's demands. But on December 31, Fish solemnly announced that, due to the growing severity of his illness, he would be resigning from council in 2020.

Fish died at his home two days later. He was 61.

Fish, a New Yorker born into a family of political heavyweights (his great-great-grandfather was secretary of state to President Ulysses S. Grant), moved to Portland in 1996 after his wife Patricia Schechter was offered a job as a history professor at Portland State University. The couple raised two children in Portland.

Fish wore many hats during his 11-year tenure on city council, but he was uniquely committed to constructing affordable housing and sustaining Portland's extensive parks system. Considered a moderate on Portland's progressive council, Fish loved helping the gears of government run smoothly. His family's political roots and own background as a labor attorney made him an eager advocate of democratic process. In his public resignation letter, Fish called his job "the great honor" of his life.

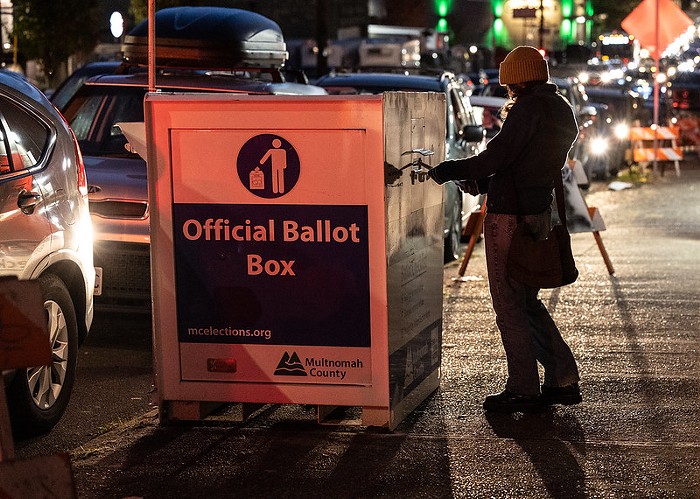

Per the Portland City Charter, Fish's seat will likely remain empty until the May primary election, at which point people can vote for that seat the same time they vote for other races. That plan has to be formally approved by City Council—something expected to take place this week—before moving forward.

A day after his sudden death, his former colleagues, friends, and (at times) adversaries shared with the Mercury their thoughts on the legacy the devoted commissioner leaves behind.

Amanda Fritz, Portland City Comissioner

"He really brought honor to the word 'politician,'" said Fritz, who joined council just seven months after Fish in 2008. "He relished all the things politicians like to do—he liked campaigning, he liked calling people, he liked bringing his kids to events and sharing those experiences."

Fish and Fritz became close friends over their shared decade on the council. Fritz's husband was killed in a car crash in 2014, and Fish, whose mother also died in a car crash, was quick to respond. He showed up at her office minutes after hearing the news, and accompanied her on the drive to the crash site.

Fritz said Fish's commitment to Portland was reflected in his refusal to trade the work for more notable government positions—particularly a certain "high level" housing policy job in the Obama Administration.

"It was his ideal job and he turned it down," said Fritz of the DC offer. "But, his family had settled here in Portland and he felt he made a promise to the city. He wanted to dedicate himself to making this his dream job."

Fritz said that Fish's background in law played a critical role in council discussions, and he'd sometimes point out legal ramifications of a policy decision that even city attorneys had missed. Fish was a middle child, which, according to fellow-middle-child Fritz, explains why he was so committed to forming consensus and helping dueling commissioners get along.

"He really brought honor to the word 'politician.'"

Fritz, who is retiring from city council at the end of 2020, believes it's important Portland fills Fish's seat with someone just as committed to compromise. She said his selflessness served Portland up to the very end.

"If he hadn’t been so honest about his cancer, people wouldn’t have known about it," she said. "He rarely missed a council session and he didn’t let up in terms of his schedule. I really honor him for that."

"It’s a huge loss," Fritz added. "I will miss my friend."

Randy Leonard , former Portland City Commissioner

Leonard shared four years on Portland City Council with Fish, a period during which the two men became friends.

"People in politics often use the phrase 'my friend so-and-so' about other politicians, but rarely they are really friends. That wasn't the case with Nick," said Leonard. "He and I continued a friendship after leaving council. I always enjoyed his company."

Leonard, who spent a decade in the state legislature before joining council, said that more than anyone else he served with in politics, Fish admirably "tried extraordinarily hard to find common ground with people."

"That didn’t just include legislating—he was the only person on council who went to almost every single after-work event," said Leonard. "I avoid most of that stuff like the plague. Not only did he do it, but he enjoyed it."

When Leonard, a Portland native, took his first trip to New York City in 2008, he asked Fish for recommendations of must-see places to visit. Leonard laughed recalling the long list he received in return—including grandiose spots like the United Nations and public library—but said he visited every location.

"I admired his courage to leave that behind and try someplace completely new. I was really impressed by that. And he truly loved Portland."

"After that visit, I remember thinking, 'This place is incredible. Why would Nick want to leave it?'" Leonard said. "I admired his courage to leave that behind and try someplace completely new. I was really impressed by that. And he truly loved Portland."

Fish's passion for his adopted city gave Leonard a new kind of appreciation for Portland.

But Fish didn't forget his roots. Leonard said Fish had a deep pride of his family's history in politics. He'd often mention how his father, former New York Representative Hamilton Fish Jr., was one of the six Republicans on the House Judiciary Committee who voted in favor of impeaching President Richard Nixon in 1974.

Leonard said Fish would often contrast that decision with today’s partisan politics. "He was constantly frustrated that elected officials were no longer holding people in their own party accountable," Leonard recalled.

Israel Bayer, former executive director of Street Roots

Bayer had been working for Street Roots, Portland's focal homeless advocacy nonprofit, for six years when Fish joined City Council with a mission to improve the city's response to homelessness. At first, Bayer was doubtful that the freshman politician could erase the longtime tensions between Portland's business community, developers, and homeless advocates to follow through on his lofty goals.

And yet, just a few years into Fish's tenure, he'd streamlined several city departments to create the Portland Housing Bureau, opened the Bud Clark Commons (the city's first transitional housing project created for chronically homeless Portlanders), and brought the Portland Business Alliance and homeless advocates—including Street Roots—together to back Portland's first affordable housing bond. The 2016 bond secured 2,000 affordable housing units within Portland city limits.

"Oftentimes, Oregon politicians wait way, way, too long to act on issues," Bayer said. "But Nick, he was well ahead of the curve on housing. He knew this stuff was going to crash in on Portland, and that we had to be ready with a longterm revenue option for permanent affordable housing. He wasn’t okay with the status quo."

Bayer said Fish was preparing for the looming housing crisis long before the polls were saying it was a good idea—long before "all politicians were housing advocates."

"He was the first one in this era to say, 'That’s not enough,'" Bayer said. "Other people on council were responsive to housing issues, but it was Nick who said, we can’t just manage this problem, we gotta find a way to fight it."

Bayer and Fish didn't always see eye to eye, but that didn't sour their working relationship.

"Even when you were mad at him you couldn't be mad at him for long. He made it okay to disagree on one front and work together on another," Bayer said. "We [at Street Roots] never could bring him over on public safety stuff. But he taught us that we can still work together on the things we all agree upon."

"Other people on council were responsive to housing issues, but it was Nick who said, we can’t just manage this problem, we gotta find a way to fight it."

Unlike some politicians, Bayer said Fish focused on longterm solutions instead of in-the-moment crises.

"Homeless policies at the city level are always wrapped up in these emergency responses," said Bayer. "But Nick was the individual who not only managed the conflict but started the plan for the next fifty years. The dude was always thoughtful... he was able to stay in the present with his mind also out on the horizon."

Fish had a grounding, almost paternal presence in City Hall, Bayer said. "It felt like if Nick was in the building, things were going to be okay," he added. "He brought dignity to the council." Perhaps more importantly, Bayer said Fish treated people living on the streets outside of the council chamber with the same level of dignity.

"It didn’t make him uncomfortable to be around people on the street, people that made others uncomfortable," said Bayer. "He didn’t care what social class you were from, it was more about building authentic relationships."

Steve Novick, former Portland City Commissioner

Novick, who shared four years on City Council with Fish, said there's one easy way to honor Fish's legacy in Portland: Shop local. In a brief email to the Mercury, Novick underscored Fish's dedication to promoting local small businesses over national chains.

"If people want to honor Nick Fish, one thing you can do is follow his example on that," Novick wrote.

Kayse Jama, executive director of Unite Oregon

Jama worked closely with Fish on a number of city policies related to Portland's diverse immigrant and refugee community, most recently one that secured funding for an immigrant legal defense fund.

"He was committed to fighting for people who were underrepresented, and never bragged about his accomplishments," Jama said. "He always wanted to listen. The longer I knew him, the more I saw that he really wanted to live his values. He was nothing but a very positive reinforcement for this community."

Jama says Fish's ability to find consensus among commissioners made him the "glue" of City Council.

"He held city council together, and he held this community together," Jama said. "Policy is always important, but showing up for the community is equally important."

Carmen Rubio, director of Latino Network and Portland City Council candidate

Rubio was one of Fish's first hires after he was elected to City Council.

"It came as a surprise," said Rubio, who had been working in then-Mayor Tom Potter's office. "At the time, I was really involved in getting young folks of color involved in the community... having their voices heard. He told me that the things I cared about were things that the city should care about for our future. Equity is really, really important to him."

After Rubio left Fish's office to lead the Latino Network, Fish would regularly check in with her to learn about new issues in the local Latinx community that he could help address. When Donald Trump was elected to office, Rubio said that Fish was the first elected official to call the nonprofit and ask how staff were doing.

"He truly just cared," she said. For years, Fish urged Rubio to run for office.

"I'd tell him I’m not ready for it. He'd say, 'You need to get ready for it.' He'd tell me all the ways that I was ready and that I could do it. He saw things that I didn’t see in myself yet. He was a true mentor and friend."

Fish played that role for many former staffers, young city leaders, and even complete strangers, Rubio said.

"There was something about the way he treated people," she said. "People felt like he was their friend even if they didn’t know him very well."

"He valued the discourse of ideas, but detested negativity and cynicism and personal attacks."

Rubio said it was Fish who convinced her in early 2019—when Fritz announced her resignation—to enter the race to fill the soon-to-be-vacant council seat.

"He called me in April and said, 'There’s going to be an announcement and a seat will open up. You need to think about this. You can do this, but it’s up to you. Just know that I’m in your corner,'" Rubio recalled. "He has been in my corner ever since."

And it's Fish's leadership style that Rubio hopes to emulate in council chambers.

"Something I loved about him was his deep, profound respect for the office and the power of elected office," she said. "He valued the discourse of ideas, but detested negativity and cynicism and personal attacks. We don’t need that, especially since we already have that happening at a national level. Ultimately, he wanted to make a city we all love better. I will gladly pick up that mantle."

Sam Adams, former Portland mayor

Adams knew Fish as both an opponent—in a 2004 run for City Council, which Adams won—and as a colleague after Fish was joined council in 2008, just months before Adams was elected to mayor. During their shared four years on council, Adams recalls Fish being someone who “agreed well and disagreed well.”

"When there was a disagreement between myself and my colleagues, I liked to keep the conversation going. Not all the people that I worked with were willing to do that, but was always game,” said Adams. "He was someone that I could count on to be interested in and open to new ideas—to having his mind changed with compelling reasons."

"He was someone that I could count on to be interested in and open to new ideas—to having his mind changed with compelling reasons."

Adams appreciated Fish’s commitment to truly understanding a complex or controversial policy issue before forming an opinion on it.

Adams, who only recently returned to Portland after a stint in Washington, DC, had breakfast with Fish just a few months ago where, according to Adams, Fish "bemoaned the lack of civility in politics and public life.”

“It was painful to him to see how, from the president on down to local government, disagreements were being used as weapons,” Adams said. "He despaired over the fact it was harder to have a discussion and learn from one another—and move then forward with as much agreement as possible. He saw this shift as especially dangerous."

Marshall Runkel, chief of staff for Commissioner Chloe Eudaly

Runkel, who was first introduced to Fish while working for former City Commissioner Erik Sten (whom Fish replaced in 2008), recalls Fish's sense of humor.

"Dude could be hilarious," says Runkel. "He definitely was a student of political theatre, and his private conversations with staff about what was going on in council... there was plenty of salty language. And no bullshit."

Runkel took a break from politics after leaving Sten's office—and didn't jump back in until running Eudaly's winning campaign in 2016.

"Dude could be hilarious. He definitely was a student of political theatre, and his private conversations with staff about what was going on in council... there was plenty of salty language. And no bullshit."

"When I left City Hall, I was deliberately unplugging from politics, I was worn out," said Runkel. He was always impressed with Fish's ability to dodge the mind-numbing and, at times, petty parts of politics.

"Nick was always able to get up and above that," Runkel added. "He wasn’t an insincere person in what can be a vapid environment. My wife often jokes that I was created in a government laboratory to work for the government. But if anyone was born in a government laboratory, it was Nick."

He was also thoughtful. Runkel recalled inviting Sten and Fish over to visit his new house sometime in the late 2000s—not long after first meeting Fish. The house boasted a retro basement with a built-in bar and shag carpet.

"Nick came over and drank beer and shot pool," Runkel says. Shortly after the visit, Fish bought Runkel a lava lamp as a housewarming gift.

Runkel has long had a photo of Fish taped to the bottom of his office computer screen, a reminder to that Fish is watching—and will always catch a mistake. Runkel has no plans on taking it down. "I need it more than ever now," he said.