The current hunger for vintage electronic sounds among record collectors and other music junkies has helped draw a number of important composers and producers closer to the pop cultural surface. One such figure is Carl Stone.

His early electro-acoustic work in the ’70s and ’80s was informed by his studies at CalArts with Morton Subotnick and James Tenney, two towering names in the early development of electronic music and modern composition. But as he started to embrace turntables, early sampling technology, and the increasing speed of computers, his music has started evolving into more granular and almost playful methods.

Stone’s most recent albums, Baroo and Himalaya, were formed using software that he has built that allows him to essentially break a music file into many small pieces which he then reconstructs at will. The results are dizzying sound collages that feel like a thousand digital music libraries colliding.

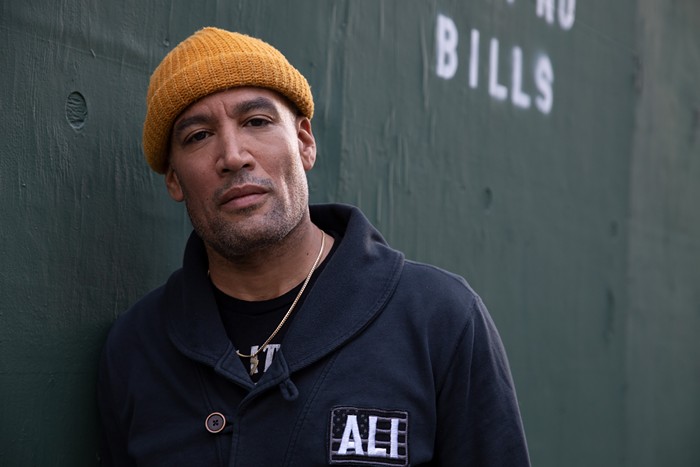

While he has called Japan home for around 30 years where he teaches classes on music technology and sound design, Stone makes regular sojourns to the States to perform live, as he will be doing on February 21 at Leaven Community, along with fellow sonic wanderers Takako Minekawa and Francisco Botello. In advance of the show, Stone hopped on the phone with me to talk about how he makes such a glorious rumpus.

PORTLAND MERCURY: I’m curious about the material on your most recent albums Baroo and Himalaya. Reading the notes about how they were constructed, I was wondering how much they change along the path of you conceiving and recording them? They don’t sound like songs that can be easily replicated.

Carl Stone: Most of them are recordings of live performances. So, a live performance like the one on Friday in Portland will be similar but not exactly the same as something that’s put out on a record. There is a certain amount of room for improvisation, for extending different sections and so on. But each piece is set up in a way that certain aspects are fixed and certain aspects are flexible. Usually, the structure I’ve set in advance is in the smaller details. Things that I can control when I’m performing live.

When it comes to the construction of a piece of music, where does it start for you? Is it hearing something in a song that you want to work with or figuring out a structure ahead of time?

Usually it starts with a play period where I’m working with some material that I’ve come across that I want to explore. In the process of playing with it and developing it, maybe a new process will suggest a kind of structure. I usually do not start out with a particular structure in mind. That comes later after this extended period of experimentation and play.

Is that process the same when you are working with a choreographer or writing something for a film?

They may have some specific ideas coming in and, of course, I try to work with that. In that case, the process is a little bit different. I’m on my own creating pieces either for the medium of a recording or for a performance. I’m not constrained by any particular form or formal ideas, so I can go whichever way I want. Very often with film, you have a director who’s trying to create a certain mood or has a particular structure and you have to fit into it in a collaborative way.

What about with your performances with the vocalist Akaihirume or Realistic Monk, your duo with Miki Yui?

Realistic Monk is completely improvised. When we walk on stage, we don’t have any preconceived ideas. The only thing we’ve decided is how long we’re going to play and even that’s going to be flexible to a certain degree. Everything else is really up for grabs. With Akaihirume, we’re working in a kind of song format. She’s written lyrics and melodies. So in that case, we’re working broadly with a structured form. We’ll start a certain way at a certain moment and be in another place and end up in a third place. But how we get from A to B to C is flexible.

The work you’ve done in recent years has been built from computer programs that you have built. Are they pretty dialed in at this point or are you still making changes and tweaking them?

I’m tweaking them all the time. “Tweaking” is a good word because the programs that I build are actually small modules that fit together and talk to each other. Over the course of performing and composing new pieces, I get new ideas, so I add features and capabilities to the programs to accommodate those. Some of the techniques I’ve been using go back since I started using this software, which is, gosh, more than 30 years.

When it comes to sampling a piece of music and playing around with it, are you seeking things out or are you just grabbing whatever captures your attention?

Something will catch my ear and make me think that I want to work with it. That’s usually what happens. I’ll be attracted to some piece of music for whatever intangible reason there might be. Occasionally, I’ve done remixes for people at their request and the material I’m sampling is fixed. So it’s a little bit different but normally, a piece of music will just jump out at me and say, “Please take me. Beat me up. Turn me around. Break me into a million pieces and reassemble me.”

You’ve been known to sample bits of pop music in your live sets, like Madonna and Cher. Do you prefer having listeners recognize what you’re messing with or would you rather it sound completely foreign to them?

I think the element of surprise is part of the enjoyment of it. I’m not trying to conceal, certainly. At the same time, sometimes it’s obvious from the first moment you hear one of my tracks. Sometimes it may be obscure. You might get it the third or fourth time you listen to it, or sometimes you might not even get it at all.

Your day job is as a professor in Japan. How much of your approach to instruction is informed by the instruction your received during your college days, when you were studying under Morton Subotnick? I got the impression that he took a very holistic approach to teaching.

He did a have a very holistic approach. He found a way further my musical education without having to sit me down in a classroom. I did take classes with other teachers, but the things I learned the most at Cal Arts came because of Subotnick’s ideas. I worked in the music library where my job was to copy every recording onto tape. It was incredible collection and it really opened my ears to all sorts of music. I basically stopped listening to pop and rock ’n’ roll because there was so much other music out there that was frankly more interesting. There was that and the added job of recording all the live concerts at Cal Arts. Student recitals and when visiting artists came through. That was a mind blowing and ear opening experience as well and they were both done at Subotnick’s suggestion.