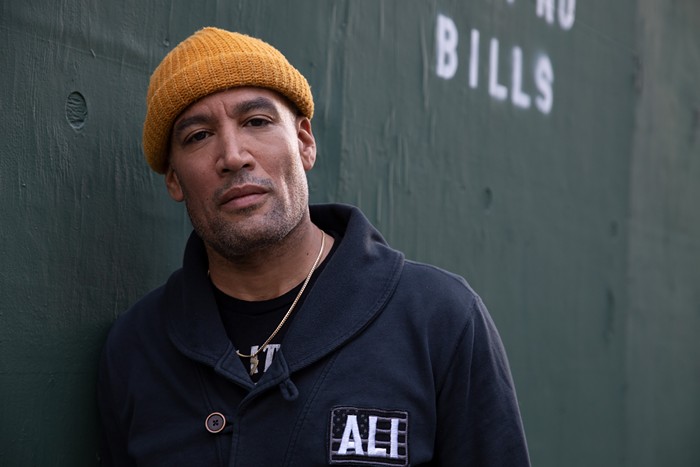

Mark Andersen

Thurs, Sept 20

Powell's on Hawthorne

It's been almost ten years since Nirvana hit the big time. We are reminded daily about what this means to the mainstream--turn on the radio and listen to the commodification of angst in action--but it is arguably the underground that was most thrown off by Nirvana's success. The underground was a world that was once quietly rumbling with music attached irrefutably with ethics; suddenly, major labels started the thrust, attempting to uproot us, one by one, with the temptation of money and fame. As Fugazi's Guy Picciotto is quoted as saying in Michael Azerrad's book, Our Band Could Be Your Life, "Ian [MacKaye, from Fugazi] once said this thing, and I think it is really true: The conversations changed after '91. Before, people talked about ideas and music. And then, after that, people talked about money and deals."

Mark Andersen puts it a little differently. "What happened then," he begins, "is that this music of the misfit and the fuck-up and the rebel isn't on the margins anymore--it's swimming uncomfortably in the mainstream. One of the things that has come out of that whole time is the fact that punk rock is a mainstream commodity, and even indie labels operate that way [above ground]." Now that DIY is a household word, and labels and bands are started so frequently, the ethics behind it--that we don't need to kowtow to corporations to validate our art--are diluted and, in some cases, forgotten.

With Washington City Paper critic Mark Jenkins, Mark Andersen is the co-author of Dance of Days: Two Decades of Punk in the Nation's Capital. The book discusses the history of punk in Washington, D.C.--arguably one of the most important, and certainly most active, punk communities that has ever existed. It begins with the insurgence of seminal hardcore band Bad Brains, follows the life of Ian MacKaye, examines the importance and eventual implosion of Riot Grrrl, discusses Andersen's own involvement in the punk activist group Positive Force D.C. and, perhaps fittingly, climaxes about the time of Nirvana's popularity. It is meticulous, gathered from over 500 hours of interviews, datelining facts and names like HR, Amy Pickering, and Chris Bald as though they are George Washington, Abigail Adams, or Ben Franklin. And, for those passionate about D.C. subculture, they are. The bands, movements, and sentiments that were born and still flourish in D.C.--DIY labels, straightedge, hardcore, and staunch ethics--changed the course of punk rock history, from a decadent, nihilistic, smash-your-guitars-and-shoot-heroin type of lifestyle to a more responsible, ethical, and activist way of life.

Functionally, aside from being the most comprehensive book about this subject ever written, Dance of Days serves a larger purpose. It is a valid work of history that, perhaps inadvertently, places the actions and development of this relatively small community into a bigger sociological context. It illustrates an age-old story and an age-old lesson: Passionate art is created from desire, and desire is kick-started by oppression and alienation. Indeed, one of the most important functions of this book is that it takes punk rock, with all its secrets, and puts it in terms that everyone can understand and--most importantly--benefit from.

"Dance of Days is for everybody--I hope that it touches people who might never have been to a punk show," says Andersen.

This is a bold statement from someone who for so long has been enmeshed in the punk scene, where selling out and punk rock ethics are still argued daily. Andersen explains, "There are ways you can pass on some ideas, but as you grow, I think Fugazi is a good example of someone who says, 'We do not want our message to be contradicted by our means. Our means is our message.' Gandhi said, 'My life is my message;' That's punk.

"I feel really lucky to have worked with [Fugazi]," Andersen continues. "They're just people; they're not saying, 'Oh, we did this, we're special.' [They're saying,] 'We're just like you. Do your equivalent in your own life. Do that in a way that isn't corrupted or compromised. Your life will be your message."

Universal as the book is, it also reinforces the case that intense grassroots happenings, like those that occur in D.C., have consistently been diluted and co-opted with their evolution. In Dance of Days, it starts on a microcosmic level, with Minor Threat becoming disenchanted with how punk became so fashionable and the message muddled, through the major label punk sweeps, to now, where supposedly DIY labels must rely upon a well-nurtured network of publicists, distribution companies, and booking agencies. The fact that, since punk broke, one can purchase a Che Guevara or New York Dolls T-shirt at chain clothing stores with sweatshop ties, is deeply disheartening.

"I think it's part of the confusing situation that the book is trying to talk about. The whole punk thing generates out of the idea that star-making machinery is bogus, that it's poisonous, and that it's the enemy of art or revolution. Or [the enemy of] truth, maybe more basically," explains Andersen. "What you have to do is get away from that machinery, and you have to scream or emote from the margin. Very few of the folks, at least in the early DC punk scene, expected to make it big or make a living out of this. It was something that people were moved to do for reasons that were unique and came from within themselves. What's happening now, in a sense, goes against that whole notion."

I ask Andersen what he thinks a collective "we" can do to counteract the utter homogenization of punk rock, to keep it from being even more absorbed into the mainstream, where its significance becomes equal to that of a brand name. I say that it's a dilemma for myself and many people I know; nobody wants to sell out, but for many, it is a dream to make a living from music--to have it be validated as an actual, important occupation in a country that does not appreciate its arts.

He's reluctant to be my punk rock spirit guide, however, saying, "I don't have a lot of thoughts on how we can fix it, but I know how an individual can do it." Andersen continues, "You have to look to your own lives, look to that original punk spirit or ethic and try to manifest that. Punk goes far beyond music. To be honest, a lot of what passes for punk these days doesn't interest me very much--which is not a put-down of that music. But to me, punk is not about three chords and rage and piercings or pointy hair.

"The answer is that we have to look deeper and apply punk's spirit, which ultimately can't be commodified, because it's beyond that realm. Punk certainly takes us beyond three chords and a certain fashion. It does demand that each one of us wrestle with that. Each one of us has to come up with the answer for ourselves. There are a lot of different points of view on how to live out punk that are described in the book. I think the essential perspective for a punk is not, 'Did HR [of Bad Brains] sell out?' or 'Did Henry Rollins sell out?' or whomever. The question is, 'Am I selling out?' And what does that mean? What does it require for me to be a punk rocker when I'm past 40 years of age and don't go to a bunch of shows, necessarily. Or when I'm working whatever job I'm working. Hopefully, it still has relevance--it remains eternally challenging.

"We just have to trust that people who are being introduced now to that punk spirit will find their way to something that seems real, and of course, we always have to be trying to find our own way. To me, that's the essence of the 'punk lifestyle,' if you will. I have very specific things in my own life, but they're less important than the general principle, and I didn't want the book to be a rant against corporate punk. I wanted it to raise tough questions in a fair and searching way.

"I think there are answers but there are no easy ones. I think one of the lessons of my experience with the D.C. punk scene is that it's good not to broadly apply one's standards to others, however good intentioned. Maybe coming at it from a different context or answer, somehow we have to try to have tolerance and keep the focus on ourselves. It's just too easy to tell others what they should be doing."

Andersen says, "If you think the music in your head isn't being played, then play that music. Same thing with these ideas that people aren't saying--go out there and get them. I'm not saying it's easy and yeah, there's racism, sexism, homophobia, this insane class structure--all these things are there to stop you. But the most inspiring thing to me about punk rock is that it says those things, in the end, do not stop you. Just the fact that you did it is a victory."