Update, 3:30 pm:

Little Big Burger has indicated that the company will not be voluntarily recognizing their union. In a statement sent to the Mercury, LBB spokesperson Jason Assad writes:

"We are not, and have never been, 'anti-union'. We do believe however, that this is an important decision and not one that should be made lightly. As such, it is our responsibility to ensure that all of our team members have the information that they need to make an informed choice. Above all, such a decision should not be made by just a few, or by the company itself. We support the rights of our team members to cast a vote in a fair, secret ballot election before choosing union representation."

Original Story:

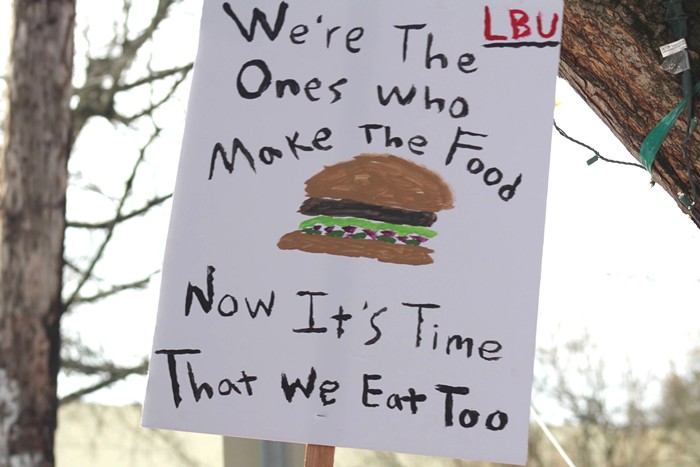

Last weekend, workers at local fast food chain Little Big Burger officially announced their intent to unionize under the adorable name of "Little Big Union."

The years of behind-the-scenes worker organizing across Portland's ten Little Big Burger (LBB) locations made its public debut with a rally Saturday, during which workers presented management with a letter requesting formal recognition of their union.

It's not entirely uncharted territory for the burgeoning union: LBB workers follow a trail blazed by the Burgerville Workers Union, which became the first federally-recognized fast food union in the country last year after a hard-fought battle with Burgerville management. LBB workers have used Burgerville worker's union efforts as a roadmap in their own organizing—and are hoping their managers use Burgerville's resistant, bitter relationship with its union as an example of how not to respond to union organizing.

"[Little Big Burger] has an amazing opportunity to listen to their workers and respond to our needs," says Ashley Reyes, an employee that's worked at the chain's NW 23rd location for more than a year. "It's as simple as that."

The union can't begin contract negotiations until its formally recognized by LBB, something that management can choose to do voluntarily or be forced to do after holding a employee-wide vote to guarantee workers' interest. LBB's union gave management until Friday, March 22 to respond to their voluntary recognition request.

The burger chain is owned by Chanticleer Holdings, Inc., a North Carolina-based company that owns a few other food chains, including Hooters.

Reyes is hopeful that LBB will voluntarily recognize their union and not delay the process with a vote that's already expected to pass. That's because LBB management has been historically receptive to worker's concerns.

As an example, Reyes pointed to a complaint made to management in 2018—line cooks at her store were cooking and preparing food while standing on non-secure rugs that would regularly cause people to fall or trip while carrying knives or tending to a vat of 350-degree oil. Reyes and a group of coworkers raised this safety concern to management. The very next morning, a non-slip mat was delivered to her shop.

Reyes said management's reception to the union letter reflected that kind of responsiveness.

"After delivering the letter, our manager asked us, 'What's one small thing I can do right now to help?' says Reyes. "We told him that workers have been cutting their hands when removing hood vents. Later that day, we had new gloves delivered to our store."

Reyes' experiences with LBB haven't all been rosy. She says the possibility that management could fire employees for any reason on any day (thanks to Oregon's at-will employment laws) is anxiety-inducing. She's seen former staff be fired on the spot and given little explanation.

"Workers are losing sleep worrying that they could lose their job any day for any reason," Reyes says.

One of Little Big Union's contract demands is creating more transparency around the company's firing process, and getting rid of the company's "at-will" policy. The union also wants to see a $5 accross-the-board raise to their minimum wage salaries. It's something Kenji Nakatomi, who works at LBB's Division store, is especially looking forward to.

"Our management likes to tell us how good we have it because we get tips. They think it makes them look like a more generous employer," says Nakatomi, who asked the Mercury to identify him with a chosen pseudonym. "But we're still making minimum wage. Tips aren't reliable. Tips aren't wages."

Nakatomi—and the union—would also like to see more stable, reliable scheduling from management. He described a wildly fluctuating schedule, planned one week at a time, where sometimes his hours are cut without warning. Nakatomi recalls management once telling workers that having a two week schedule just isn't convenient for upper management.

"The fact that the company views workers' gains as their losses," says Nakatomi. "That's offensive and devaluing."

He hopes LBB won't copy Burgerville's icy response to its fast-growing union. Burgerville refused to voluntarily recognize its union, and has been allegedly using classic union-busting tactics to discourage would-be union supporters.

"We want management to learn lessons from Burgerville's errors," Nakatomi said. "[Burgerville] doesn't know what's good for them. It's not a good look to union-bust, especially in Portland."

Both Little Big Union and Burgerville Workers Union (BVWU) are affiliated with the national labor union Industrial Workers of the World. BVWU has put their union muscle behind their new sister union, and are hopeful that, in Portland, two burger unions are better than one.

"If the BVWU stood alone, the industry CEOs would likely dismiss us as a one-off curiosity," BVWU wrote in a media statement. "But today, for the first time in nearly three years, we are not alone."

It continues: "We believe the Little Big Union to be the next great leap towards working class justice, the lighting of a fire under all low-wage workers in food service, reminding us that all work has dignity, that a better world is possible."