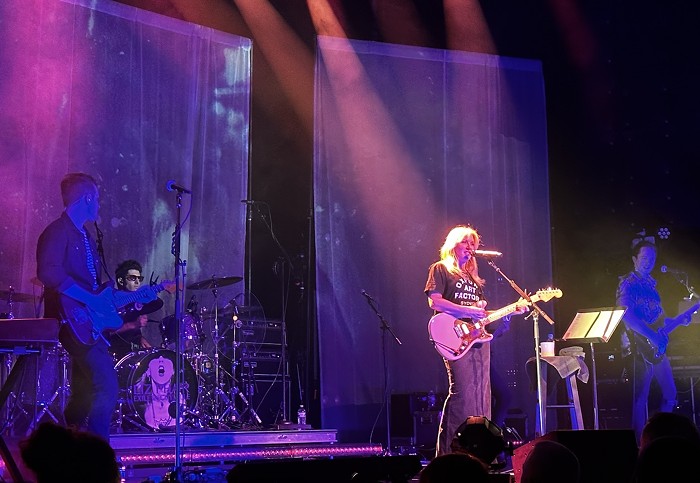

band photos by Jeff Mawer - outdoor photos by Zak Riles

It's no secret that times are hard in Portland.

Located deep inside the anus of the U.S. economy, it's a natural habitat for unemployment; where schools suck, social services crumble, and nightclubs disappear. The Blackbird, a popular joint located on the deadly corner of NE Sandy and 37th, is the latest addition to this laundry list. Unable to make rent and facing eviction, the club's doors will be closed by the end of the month, joining the rank of failed clubs littering Portland's recent history.

Although the owner, Pat Kenneally, opened its doors only two short years ago, the Blackbird almost immediately became a defining influence on Portland's relationship with music. Many will be shocked that such a popular, well respected club could have been doing so poor financially. However, the ideals on which Kenneally built his business were also the cause of its inevitable demise. Nobody involved with the club is surprised by its closure--which was more or less anticipated since its inception. But it remains to be seen how Portland music will be impacted in its absence and influenced by its philosophy.

A CLUB FOR MUSICIANS

Musicians took top priority at the Blackbird, earning it a nationwide reputation as a favorite club among touring bands.

Chantelle Hylton, the club's booking agent, says, "People always point me toward websites where bands have written the Blackbird is their favorite place to play." Onstage at SXSW, Hot Hot Heat gave it props. The buzz was significant enough to pervade the whole of Portland's club economy.

"I think it made other clubs in town really take stock," says Kenneally. "Even though they were competing with a club half their size."

Unlike most clubs, the Blackbird went out of its way to support the musicians who played there, even to the detriment of its own existence. Joseph Kelly, a bartender who's worked at the club for its entire span, remembers that in the beginning, bands kept all of the door money, instead of the standard practice, which is using some of it to pay the door and sound guy.

"It would've only taken the most basic knowledge of business to have paid this place off in a year--then [Kenneally] would be coasting and everybody would still have jobs," says Kelly. Still, as a touring musician himself (the Blackbird's staff is almost entirely comprised of musicians), Kelly appreciates the difference it makes for the Blackbird to have gone the extra mile to welcome its performers, even down to details like food and drink tickets.

Recalling one tour stint, he says, "It kept coming up how we wished there was a Blackbird in every city--three drinks and a meal instead of two fucking Budweisers."

On the other side of the bar, many of the club's patrons were also musicians, creating a mutually supportive, community-based environment. Sara Daley, who was the club's bar manager for the first year and a half, and one of the only non-musician employees, recalls the growth of the club.

"I would serve all these guys, and eventually I would see them onstage," she says. "This was a place for musicians to hang out and support each other. It was a real honor to be a part of that."

Despite being known as a musicians' haven, there were problems with the club from the start. Kenneally candidly stated that "The 'beginning of the end' was the beginning." Hylton agrees, noting, "We really did know from the start that in order to be successful we would have to compromise--but we just pretended to ignore it." Kelly remembers working for free, in hopes that it would help out. Now the experience has left him "just fucking spent."

As the club circled the financial drain, Kenneally entered into discussion with a number of parties who considered purchasing the Blackbird. Though nothing was ever signed, there was talk of a joint ownership that included Kelly, Hylton, and two of the club's other employees. It fell through, however, and the club continued to scrape by without enough profits to implement any real improvements.

The average patron, without being ensconced in the Portland musicians' community, and unaware of the underlying camaraderie, would often have complaints. For one thing, the club is a relatively small space, particularly considering the draw it had on some nights. Kelly remembers the excitement when the club first opened, and how it was packed to the gills to the point of nuisance.

"Some people refused to come back because it was so crowded the first time they went," he says.

One of the primary logistical problems the club faced was the fact it was all in one room, without a separate space that might have supported more significant revenues from food sales. The club's vegetarian and vegan-oriented menu is remembered by Daley as "admirable," but the inconvenience of eating at crowded shows and the lack of a space to go and get away from the noise level hurt the restaurant aspect of the business. "You can't just be, 'We're here, we have music.' It's not enough," says Daley. Ironically, there's a possibility that the next incarnation for the Blackbird space will be as a health food restaurant.

A ROOM TO CALL OUR OWN

Despite the Blackbird's short shelf life, its closing could still cause a huge impact. Perhaps other club owners will take a page from the Blackbird's book, reconsidering their own priorities in terms of the way musicians were treated. Perhaps the closure will inspire them to book bands because of their faith in the artists, rather than an eye towards the numbers. Perhaps, but unlikely.

"I'm not sure clubs should book the way we did," admits Hylton, "because they wouldn't last for very long."

At the very least, the Blackbird's crash and burn signals a shakeup in the indierock community, leaving a space that begs to be filled. However, in such dicey economic times, it seems likely to expect an even higher turnover of clubs, which is a fickle business even under the most ideal conditions.

But the spirit of compatriotism that Kenneally and his staff brought to the Blackbird can certainly transcend the confines of a rented building. Hylton estimates that 300 bands have moved to Portland within the past two years, and they keep coming. With this over-saturation of talent, perhaps it's time for Portland to examine how it means to support an ever-expanding artistic community.

For the immediate time being, Hylton has shows booked through mid-December that are now looking for homes. After that, she's considering booking independently under the moniker "Blackbird Presents" in order to honor the club's memory and to "let people know those shows are in keeping with the philosophy of the way we did things at the Blackbird which sort of means I'm gonna lose money."

Kenneally has plans to throw a goodbye party, but probably not in the Blackbird space. Kelly and his co-workers are available for employment. As for the rest of us, we should consider putting on our basement shoes and reviving the house show, or perhaps stake out the clubs for a new stomping ground. Because no matter how many clubs come and go, the community should be perfectly capable of sustaining itself artistically. All we really need is a room.

The last show at the Blackbird will be Saturday, August 30 with Deerhoof, Lil' Pocketknife, The Planet The, Degenerate Art Ensemble, 10 pm, $7-8 The End Was the Beginning The Blackbird Closes, Leaving Portland Looking for a New Indierock Heaven by Marjorie Skinner