How to Disappear Completely and Never Be Found begins as a textbook expression of existential discombobulation à la Sartre's Nausea, complete with a protagonist compelled to worry at the surface of reality like a puppy who's just begin to suspect that the bone he's chewing on might be made of plastic.

"I think things might actually be shit," declares Charlie (Cody Nickell), an ad exec who finds himself losing control of an existence that didn't seem all that great to begin with. He passes out on the subway and comes to in the company of a deranged security guard (the fantastic Ebbe Roe Smith), who introduces him to a subterranean world of things people leave behind—cell phones, umbrellas. Charlie starts getting nosebleeds during ad pitches; his doctor prescribes him a Valley of the Dolls-worthy array of pills. And worst of all, he's troubled by the nagging sensation that what he perceives as reality is actually a thin membrane containing nothing but gray sludge.

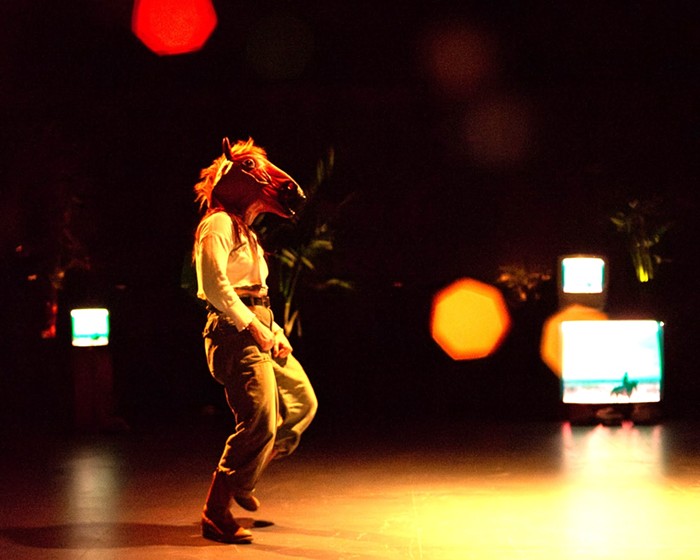

Soon he's busted for embezzling money from his firm to float his spendy coke habit, but instead of 'fessing up to his crimes, he tries to flee from his life and himself, seeking out an old family friend, Mike (Smith, again), who schools him in the art of shedding one's identity. A clever white set, full of hidden drawers and doors, is arrestingly bleak, yet full of possibilities; and if Charlie's first-act angst feels a bit textbook, all is redeemed in act two, when playwright Fin Kennedy moves beyond musings about the sludgy nature of reality to consider Charlie's ultimate fate.

Every good existentialist anti-hero knows that freedom implies responsibility, but clearly Charlie never had the benefit of this reviewer's French lit classes, and he ultimately can't escape the fate that's his from the moment he decides to flee his life. This failure, provocatively described and expertly produced, makes How to Disappear an appropriate parable for an over-entitled and under-satisfied culture.