"PLAYING MUSIC with someone is just really intimate and scary," says Marissa Seiler of the self-described devotional-punk trio Golden Hour. The collaborative group is a great example of Portland's punk community, and it's clear the three share a deep empathy with one another, which started when they were college friends with a passion for music.

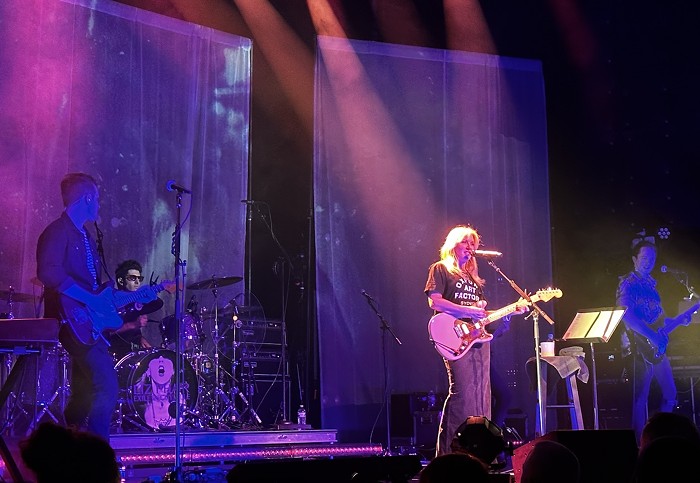

I meet with Seiler (guitar, bass, vocals), Katie Krussel (drums, vocals), and Alex Hebler (guitar, bass, vocals) right after they finished their set at the Mercury's monthly free Ear Candy showcase at Mississippi Studios. It was the first time they'd ever played the prominent Portland club. As a minor, I wasn't able to watch the show, but from outside, I could hear Golden Hour deliver fiery, emotional renditions of songs from their 10-song debut tape, Don't Be Cute. My interview with the group is punctuated by praise from fans exiting the venue, including Jem Marie and Nsayi Matingou of fellow punk act the Ghost Ease.

"I appreciate that you are meeting with all of us, so you could get all of our inputs," says Krussel, and indeed, collaboration is one of the group's top priorities, along with a DIY ethic, evidenced in the making of Don't Be Cute. It was recorded in the basement of friend (and Mercury contributor) Mac Pogue, and Krussel designed and screen-pressed the tape's artwork herself.

They recorded Don't Be Cute live, and with the exception of the song "Arm Teenage Girls," it was all done in one take. This brings a natural rawness to each track, but the songs are unexpectedly layered, too, combining shrill guitar riffs, sludgy bass lines, and wildly cascading drumbeats. Golden Hour are a decentralized punk band without a straightforward "lead singer"; the trio shares songwriting duties. Plus, the group's atypical vocal harmonies often feature all three members at once, and can sound both like a haunting shred and a comforting blanket in the span of a single song.

"We all wanted to be in a band," says Seiler, "but we felt like we could only do it with people we were really comfortable around, so we played secretly in my garage. It took a long time for me to claim the identity of musician. I didn't even name it 'band practice' for over a year."

As Golden Hour developed their collective voice, Portland's DIY and all-ages spaces became increasingly scarce, with the closing of long-running venues Laughing Horse, the Red and Black Café, and Slabtown. The community continued to thrive, though, with house venues and nontraditional spaces, including North Portland's Anarres Infoshop, which has consistently held shows for local and touring DIY acts since opening earlier this year.

"We've been really grateful for getting to play such awesome shows at Anarres," says Hebler. "We just recently played with Downtown Boys and it was one of the best experiences of my entire life because one, Downtown Boys fucking rules, and two, Anarres does such a good job booking a spectrum of different bands and creating an inviting space. Anarres has a lot of new energy to it, and I've felt good about every show I've been to there. I have yet to have an experience where it's a bunch of bros being totally obnoxious."

Historically speaking, some of the city's best music has been created surrounded by the ongoing struggle, support, and perseverance of the DIY community—from the riot grrrl bands of the 1990s to Osa Atoe's many mid-2000s projects. What remains constant within the community is that each band and individual's experience is different, which is essential to recognize when working against systemic racism, sexism, homophobia, and classism. For example, my personal understanding of intersectionality comes with the inherent bias of my straight-white-cis-male privilege, leaving me with the role of acknowledging my privilege and stepping back to help make space for other voices to be heard. It's an invaluable lesson I've learned—and one that, ideally, creates a support system for those combating oppression.

"We have been invited to take part in queer, women, POC [people of color]-centric shows," says Krussel, "and this feeling of support and being a part of something bigger has been a huge part of our gathering courage to be a band and write the songs we do. I think we come to expect the status quo, but as we have seen, bookers and bands have been focusing on anti-oppressive action. There is real community among us—musicians that are women, queers, and POC have intentionally shown their support for us. It's not just some white guys telling us we should be onstage."