A BLACK CAT followed me right into Shaking the Tree's warehouse theater during one of the company's first performances of Tennessee Williams' Suddenly, Last Summer. It was a good omen for a play where a character literally shouts out "Cymbals!" during a finale heavy with... symbols.

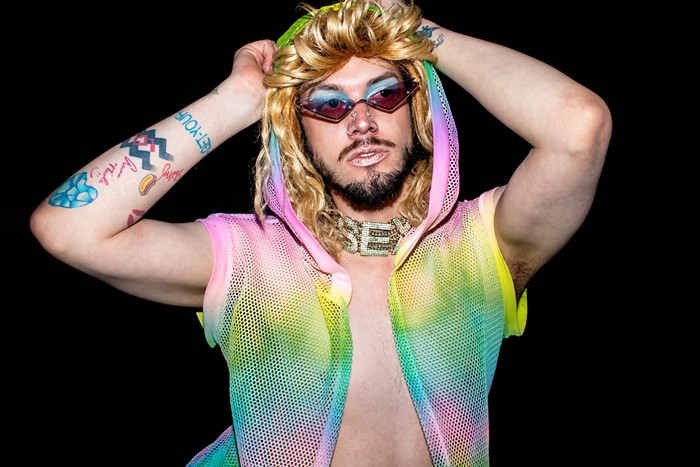

Inside, Director/Set Designer Samantha Van Der Merwe had constructed a habitat reminiscent of Twin Peaks' Black Lodge gone tropical, with semitransparent curtains and gauzy, oversize paper flowers, and a sound loop mimicking the play's New Orleans garden setting. There are no Southern belles in Suddenly, Last Summer: Instead, there is Violet Venable (Jacklyn Maddux), whose son, Sebastian, died under what she considers mysterious circumstances. They aren't really: Sebastian's cousin, Catherine (Beth Thompson), witnessed his death, but because her story includes the knowledge that Sebastian was gay, Violet will do anything to avoid accepting it, including having Catherine committed, or worse.

Here's an awkward admission from a theater reviewer: Though I love Kristen Schaal's impression of him on the Dead Authors Podcast and Christopher Durang's jokey sendup of The Glass Menagerie (For Whom the Southern Belle Tolls, recently performed at Post5 Theatre), Tennessee Williams' plays often strike me as the theatrical equivalent of Russian novels. I know they're extremely important to literature as we know it, but I don't want to read them, like, right now.

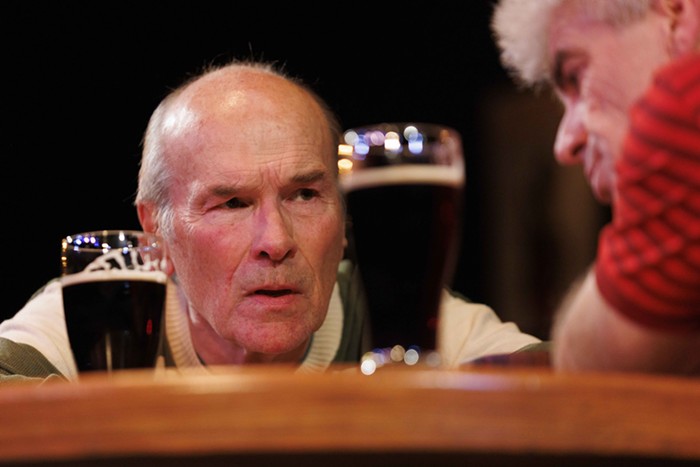

And taken at face value, Suddenly, Last Summer wouldn't appear to dissuade that lazy impulse, overflowing with a toxic stew of horribly dysfunctional neuroses. Violet's obsession with her son reads just a skosh above flat-out incest—she slurrily claims that they were "a couple," and now moves through her days with crutches: one, a 5 pm daiquiri, the other a wheelchair pushed by her maid, poor Miss Foxhill (Rebecca Ridenour), though it appears she can maybe actually walk? Violet's sister (Luisa Sermol) and her nephew (Steve Vanderzee) also have a weird, way too touchy vibe, and Catherine is accompanied at all times by a nun (Dana Millican) entrusted with her psychiatric "care." If that doesn't sound like the worst family reunion ever, consider that one of the play's more likeable characters is AN ACTUAL LOBOTOMIST. NAMED DR. SUGAR (Matthew Kerrigan).

In lesser hands, this could devolve into soupy, over-acted melodrama. But the actors are game, and Van Der Merwe's direction is delightfully out there, pulling out the play's repetitive, strange language, and employing inventive techniques—including amazing work in sound, lighting, and projection—to convey the fact that Catherine, though committed to an asylum, is the play's most reliable narrator. In the final scene, she recounts what happened to Sebastian with a fugue-like delivery and staging that left me with goosebumps.

There's a reason for this. Williams based Catherine on his sister, Rose, whose own lobotomy at the age of 24 was "a source of torment" for him. Rose's tragedy, then, becomes the play's emotional center, in the form of Catherine's survival, which depends not on whether she's telling the truth (she is), but whether anyone else believes her. It's a damning view into the way mental illness, particularly for women, has been used historically to silence appropriate human stress responses—or in this case, the truth.