The annual Oregon Shakespeare Festival (OSF), in Ashland, Oregon, has been rolling on since February. So why haven't you been yet? Well, with 11 productions spread across three stunning stages, a driving time of nearly five hours from Portland, and ticket price tags approaching $70, you're probably feeling a little overwhelmed by the whole endeavor, if you've thought about it at all. I almost didn't go myself this year, but reconsidered after realizing three of the current productions had something interesting to offer: Our Town, Othello, and the seldom-done Coriolanus.

Our Town

My first experience with Our Town, as I approach the age of 30, was far from sentimental or dull. On the contrary, I was happily surprised by the morbid underpinnings of Thornton Wilder's staple of high school drama clubs. The final act finds female protagonist Emily dead and adrift, wandering aimlessly through a sea of similarly dead residents of her town. Director Chay Yew handles these delicate final scenes with eerie simplicity, the deceased townsfolk sitting in orderly rows, staring vacantly into nothingness.

From the beginning, this production is quiet and meditative. As Stage Manager, the funny and delightful Anthony Heald guides us as characters eat dinner together, throw a ball around, and generally perform the classic rites of small-town America. Yew slows their actions down, mutes them, as if they are ghosts already. It's a fitting vibe for a play that is, finally, a rumination not so much on death's inevitability as on life's impermanence, and the importance of appreciating every last, insignificant, tender moment.

Othello

Director Lisa Peterson seems unsure what to do with Shakespeare's most senseless tragedy, Othello. Her cast carries old-fashioned, swashbucklin' swords around, but then panels of florescent lights will suddenly crackle to life, bathing the stage in ultra-modern retro chic. The play's Fool is, for no reason I could fathom, played by a tiny Asian child; and, worst of all, a trio of "live" musicians wanders between scenes, actually pretending to play their instruments to a prerecorded score.

Othello's performances, nearly across the board, are as middling as its technical elements, with Peter Macon leading the charge as Othello. Wearing way too much eye make-up, the somewhat portly Macon plays Othello with an affable bemusement lacking in menace or warrior power of any kind. Next to fiery redhead Dan Donohue's Iago, Macon's Othello feels like a minor character, a not-uncommon outcome of Othello, though rarely to the degree seen here. Donohue imbues Iago with such seething, irrepressible rage he can barely speak at times. His Iago is an uncomplicated, unbiased hate monger, with equal vitriol to spare for all humankind—and it is an absurd joy watching Donohue continually find new and unexpected ways to convey rage. Too bad it's wasted on a lame production.

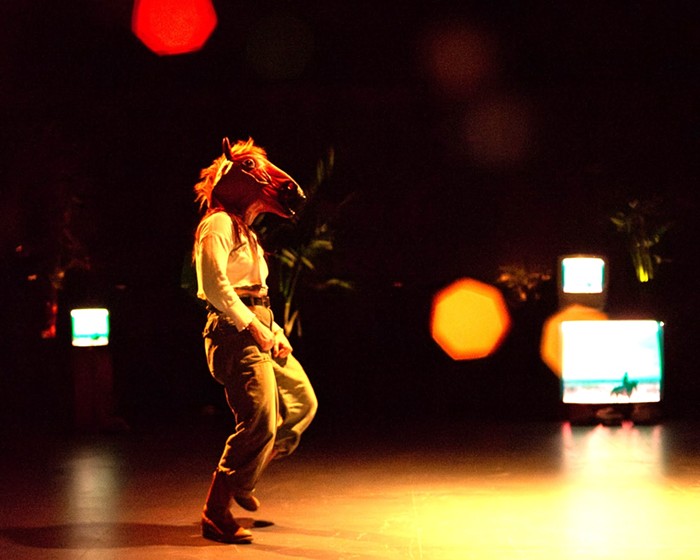

Coriolanus

Unlike Hamlet and other great individuals of the Shakespearean canon, Coriolanus, played here by the fierce and indignant Danforth Comins, seems to willfully avoid soliloquies and other means of revealing his inner thoughts. We know he is a war hero who loathes the common people whom he has been assigned to protect. We know his mother, Volumnia, is an overbearing presence in his life; and we know he has been honed from birth to be an efficient killing machine. Coriolanus is an unlikable character, but Shakespeare makes us see his caustic nature as a product of a system outside himself. And when he dies, killed at the hands of his rival Aufidius, we grieve over what war did, what it made.

Director Laird Williamson does with this material what a great director should, making it into something that not only seems relevant to our time, but as if it was indeed written for our time. Clad in combat fatigues, carrying machine guns and other scary weapons, Coriolanus' army seems embroiled in an all-too-familiar political struggle, battling both the gritty Volscians and its own people, a crew of hoodie-wearing rebels who resist Coriolanus' naked pride and ambition. But Williamson's most brilliant touch is turning the play's "tribunes," a duo of "speakers for the people," into laptop-slinging, badge-wearing members of the press corps. Coriolanus thus becomes a commentary not just on war, but on the entities that feed it: namely, the media and the citizens—us—who blindly let the media guide their/our thoughts and actions.