PORTLAND THEATER COMPANIES have done an unusually good job recently of making audiences cry (see: The Big Meal, The Outgoing Tide), but it's far more difficult to elicit another gut reaction: fear. Maybe it's because theaters are some of the safest spaces imaginable, but plays aiming to frighten usually fall flat.

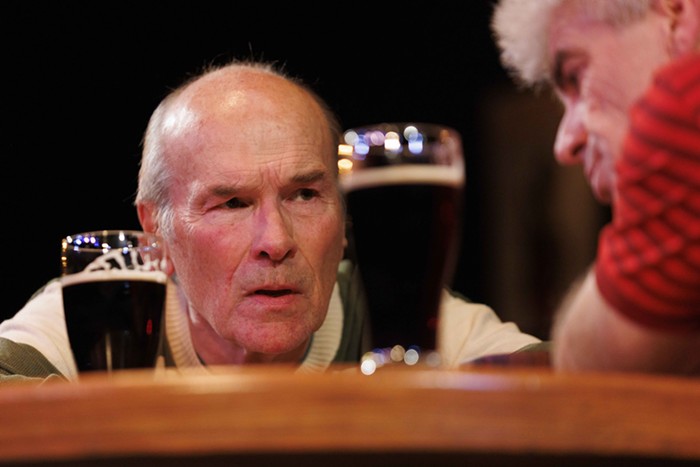

Theatre Vertigo's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is no exception, despite some valiant performances from the ensemble, most of whom juggle multiple roles in fleshing out Jeffrey Hatcher's adaptation of the classic tale.

Packing 40 or so seats along the length of two walls of the Shoebox Theater, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde opens with a disorienting tumult of flashlights in a pitch-black theater. It's a good start, taking advantage of the small space—and soon, a scene featuring a creeeeepy surgeon autopsying the body of a prostitute introduces a promisingly lurid, sensational element.

Hatcher's script is most interested in the psychological split between Jekyll and Hyde, going so far as to enlist multiple actors to play Hyde, each showing different aspects of the base nature that the good doctor Jekyll is so eager to winnow out. But these elements are sidelined by the logistical constraints of the space, and by direction that prizes style over subtlety.

This is Vertigo's first performance in the Shoebox—after losing their home at SE Belmont's Theater! Theatre!—and the actors are clearly still getting used to working at such close proximity to their audience. Kerry Ryan and Mario Calcagno effectively calibrate their performances to the spectators sitting three feet away, but other actors still seem as though they're playing to a much larger space; this can make the show feel campy when it's aiming for creepy. (This goes double for some of the fight choreography, which shows its seams at close range.) Rather than being immersive—or better still, immersive and frightening—the staging just seems clumsy; there's a lot of pacing from one end of the narrow theater to the other.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is most successful when it's exploring the struggle of a man trying to entirely suppress his worst impulses, but Bobby Bermea's direction favors stylized menace that fails to frighten, while steamrolling psychological complexity. The result is a show that feels the wrong size for its venue: It's not immersive enough to be scary, but it's too cartoonish to be psychologically compelling.