THE ACADEMY AWARD pretty much seals it: The tale of Rodriguez will be a tough one to top.

Still, intriguing and somewhat similar stories to the one documented in Searching for Sugar Man are also told of Charles Bradley, Sharon Jones, and others like them—young soul singers all but lost in the 1970s, who only found audiences once they themselves had turned 70 (give or take a few years for Ms. Jones and Mr. Bradley). It's practically a new genre. Call them something like the "Lost and Found."

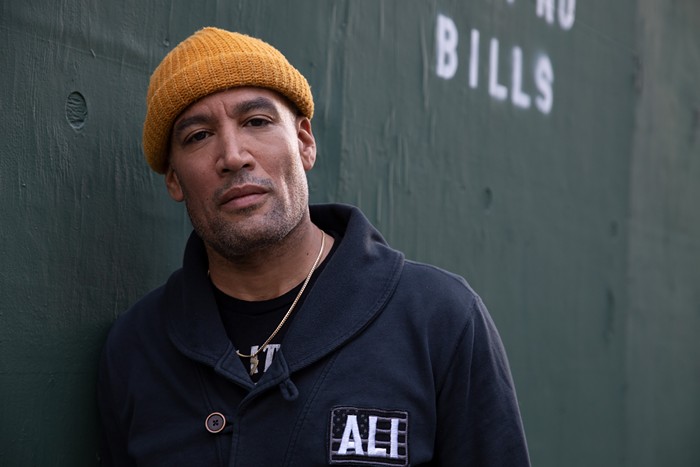

And their ranks are growing. Add to them the Relatives, a searing gospel group from Dallas, formed in 1970 by Reverend Gean West. Before a Temptations-inspired vocal front line, the good reverend gets downright bad.

"The Relatives sing a burning gospel refracted through the lens of psychedelic rock, heavy R&B, and 1970s funk," writes James C. McKinley Jr. in a recent New York Times profile. "Their riffs and drum grooves owe as much to Jimi Hendrix and Sly and the Family Stone as to the Reverend James Cleveland and Shirley Caesar."

Throughout the early '70s, the Relatives released three singles that never found a proper home. They were too funky for church, too churchy for funk. By 1980, the Relatives had dissolved.

But in 2009 an old 45 led vinyl collectors in Austin to a trove of unreleased material. West then reformed the group along with two principals and support from a younger generation. Last year the reignited Relatives recorded a new album with producer Jim Eno of Spoon. It's electric, psychedelic, airy, serrated, cathartic, and fucking great—like Funkadelic, except instead of sex and acid, the Relatives get high on God, harmony, and the Golden Rule.

McKinley's Times piece suggests that the (re-) emerging affinity for the Relatives—and others like them who make up the Lost and Found—is a reflexive grasp toward "a rougher, handmade sound, an authenticity rooted in a place and time," in opposition to today's increasingly homogenized digital world.

But forget for a moment the vintage recording techniques, the classic soul tropes, and the creation of music as a group experience. To embrace the Lost and Found is also to be counted in opposition to history, against old ideas on race, politics, class, and business—the very ideas that held these artists back originally. In person, particularly, there is the sense of wanting to right past injustices. (As a fawning fan called out to Rodriguez at a recent sold-out show: "You deserve this!")

Indeed, the message matters. Two themes permeate the Lost and Found: First that something is wickedly wrong with America today, and second, that it shall be met with a loving heart and adherence to the Golden Rule. That these messengers, delivering these supposed elemental truths, are well into their third acts is of great significance.

Which is to say nothing of shifts in marketing and accessibility, or how the Lost and Found could just as easily be late bloomers. Nonetheless, they're not playing for tomorrow—or yesterday, for that matter. The Lost and Found are very much of the here and now.