THERE'S A particular subcategory featuring flawed, hard-boiled lady detectives and/or spies that's lighting up teevees across the country right now—praise be to The Fall's Detective Superintendant Stella Gibson, Marvel's Jessica Jones, Homeland's Carrie Mathison, and OG Detective Olivia Benson. So it was only a matter of time before Action/Adventure Theatre, purveyors of youthful theater that appeals to those of us who watch too much Netflix (THESE THINGS EXIST!), entered the fray with their latest, the Portland-set Hawthorne, featuring antiheroine private investigator Anne Winters (Zoe Rudman). And I'm so happy they did. (I may have said "YAY" as soon as I saw the synopsis. I may have.)

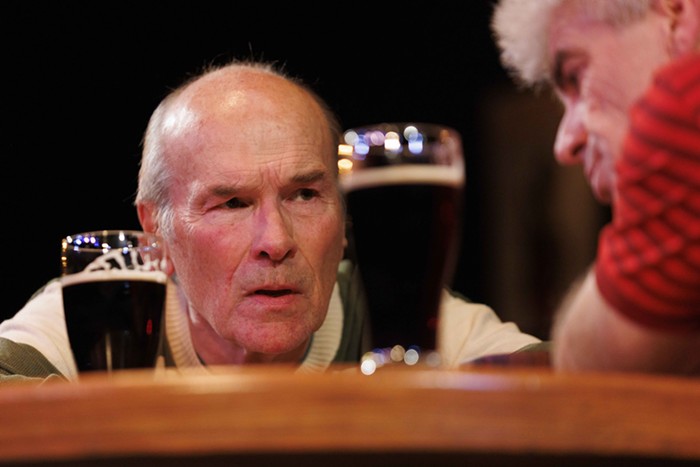

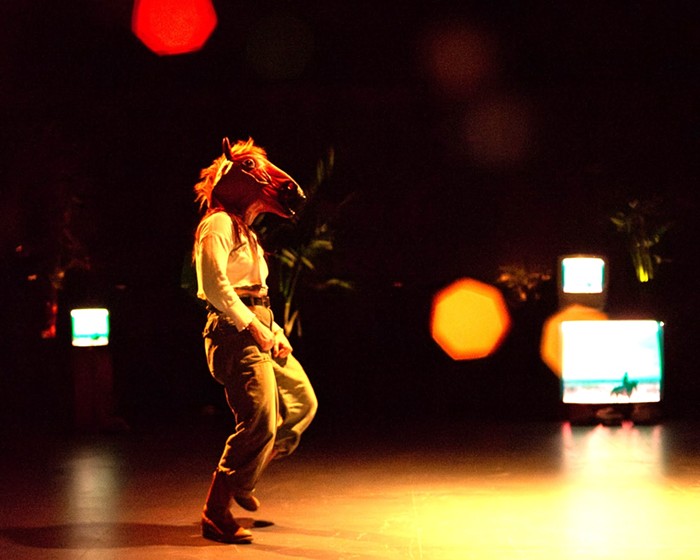

Though it's noticeably slower than Action/Adventure's typical offerings, which are often kinetic verging on mercurial, Hawthorne has a lot going for it. A pleasant deviation from the theater company's serialized format (this is kind of a relief for those of us with self-defeating completist tendencies), it employs a mostly female cast and a number of subtle and less-subtle gender reversals to soundly fuck with the noir genre's typically rigid sex roles—the world-weary PI's a hard-drinking woman who struggles to relate to other people, there's a sensitive missing ex-boyfriend where you'd normally see an idealized, supportive archetypal girlfriend speaking from beyond the grave or wherever. (When it all comes down to it, "I couldn't save her!" is the refrain, even, of James Bond.) The dialogue, by Action/Adventure's Aubrey Jessen and Greta West, who also co-direct, flows with humor and plausibility, and makes reference to the hyperlocal without getting cutesy about it (the way lesser theater companies might).

While some scenes go on a bit too long, or dip into camp, what's wonderful about Hawthorne is that it actively resists the squeaky-clean, quirky-dumb depiction of Portland seen, you know, everywhere. Instead of jokes about tall bicycles or whatever the fuck, we get shades of Twin Peaks and Bored to Death (but way fewer whiny male novelists) in a cinematic atmosphere that's restrained, but with an undercurrent of anxiety, or maybe just pain, that never really goes away. It's occasionally darkly comic—and often just dark—which is exactly what a noir should be.