I’ve been covering the PICA's Time-Based Art Festival for the better part of a decade. I’ve found writing about the contemporary canon to be both satisfying and deeply challenging. In many ways, reviewing means looking at the work more closely and acutely. I lean in, because it’s my job to really try and parse what the artists intend to communicate. And in my experience, it has always been the “big” shows, the ones with the grandest schemes and the most grandiose ambitions that tend to be the hardest to write about. Faye Driscoll's Play, the second installment in her Thank You For Coming series was no exception. So bear with me, if you will, as I attempt to unpack this captivating and complex performance.

What I know for certain is that Play had structure. A prologue and a first, second, and third act. So let's start there. In the prologue, the audience is ushered into Imago Theatre's performance space and encouraged to sit on the floor around a rectangular white platform, while actors move through the space, sometimes crouching beside audience members and asking them to participate. There are also a few actors handing out note cards and pencils. The note cards have blanks to fill in, like, "I really miss_________ (someone, something, some place)" or "What I want right now is________ (something, someone, sometime)."

This all goes on for about 20 minutes, until the actors have seemingly sorted all the returned cards on the white platform in an order they approve. They take their places, singing a note in unison, we're told we can take our seats, and the stage manager points to the open theater seats in the theater. The crowd moves and the set changes. At the time, I didn't have the opportunity to think on what this first movement was getting at, but now I see it was a way to build a sense of community.

Act One: Perhaps the performance's most sudden shift in tone, it begins with high energy. The actors are now adorned with clown-like representations of Greek or Roman style garb. They over-gesticulate, they over-enunciate, they speak in a sort of hifalutin English, and they communicate through absurdity. They are telling the story of a character named Barbone (this author's spelling) and we're more or less treated to this character's birth, life, and death. I say more or less because the telling isn't straightforward. We hear the details of Barbone's life through song, gesture, mime, dance, slapstick, and fantastic physical comedy. Barbone is played by multiple actors (sometimes simultaneously) and Barbone's pronouns shift often (he, she, they, etc). Here, Driscoll shows that the story is for and by all of us. This is further emphasized by the periodic use of the note cards from the prologue, read as though they are scripted narration. Barbone is all of us.

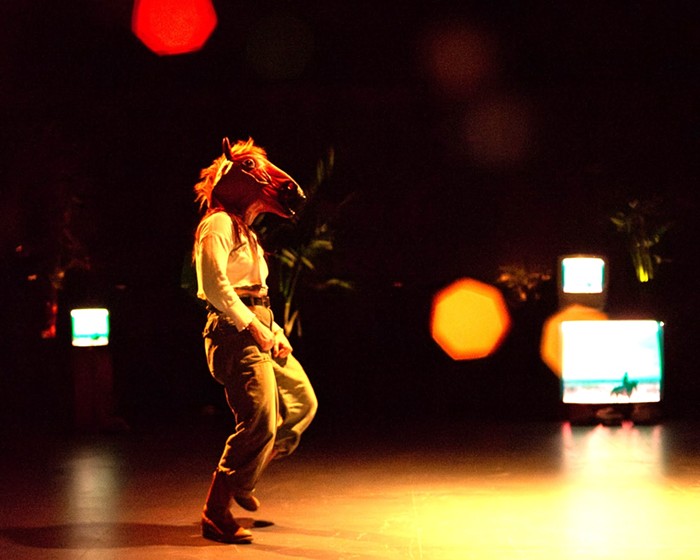

Act Two: The actors are now back in their "rehearsal garb," seemingly playing themselves again. They're midway into a discussion. About a breakup? About how it is easy to feel isolated in a group? I phrase these as questions because Driscoll doesn't exactly let the audience catch up. The actors begin to short out their words while still mouthing them, and begin to mime and move about the space. Soon, audience members are chiming in. Toward the end of the act, these audience members (clearly plants) come onstage and join the actors.

This made for a head-scratching experience. It was the section of the show when I started to feel the most lost. I think many in the audience were with me. I want to say that this was adding onto the growing theme of what it means for an individual to be a part of a group, as if isolation is our only real truth. But I can't be sure. I can't think of a moment that exactly signified that.

Act Three: The stage lights blink off, and a spot light appears on a chair in the middle of the stage. The stage manager sits in it, notecards in hand. She starts to recite a poetic speech as she flips through the cards. We are led to believe that she is reading our words but it seems highly unlikely that this was an unscripted moment. I did hear my own card read toward the end of the speech, which I took as an attempt to make the trick feel more real. When the theater went to black, I was left wondering how these three pieces worked together.

This leads me to perhaps my greatest critique of Play: It lacked continuity. I wonder if Driscoll and her ensemble were, in the end, asking too much of their audience. It's one thing to empower your audience to fill in the gaps on their own; it's another to make your viewer feel isolated, or worse yet, stupid.

Play made me to think critically (more so than any artistic piece in recent memory) about how communities can negatively impact individuals. It's something to keep in mind in our present moment, as picking and participating in the right tribe is basically becoming a survival tactic. And in the end, I'll take it. At a performance like this, your brain gets some exercise, and you'll probably burn calories from the laughter.