There’s been no shortage of scrutiny directed toward Portland Public Schools’ (PPS) administration and board of directors in recent months. Voters will have the chance to shake up the school board in the May 21 special election—and prickly issues like budgeting, racial equity, and district accountability have so far dominated the race.

The candidates

Four out of seven seats on the PPS board (not counting the student representative seat) are up for grabs this election cycle, and only one race includes an incumbent board member. In Zone 1 (here's a map of the different zones), Metro interim chief operating officer Andrew Scott is running unopposed to succeed retiring board Vice Chair Julie Esparza Brown.

Michelle DePass, a community engagement policy coordinator at the Portland Housing Bureau, is running against Shanice Clarke, the program coordinator at Portland State University’s Pan-African Commons Student Center, for the Zone 2 seat that’s about to be vacated by Paul Anthony.

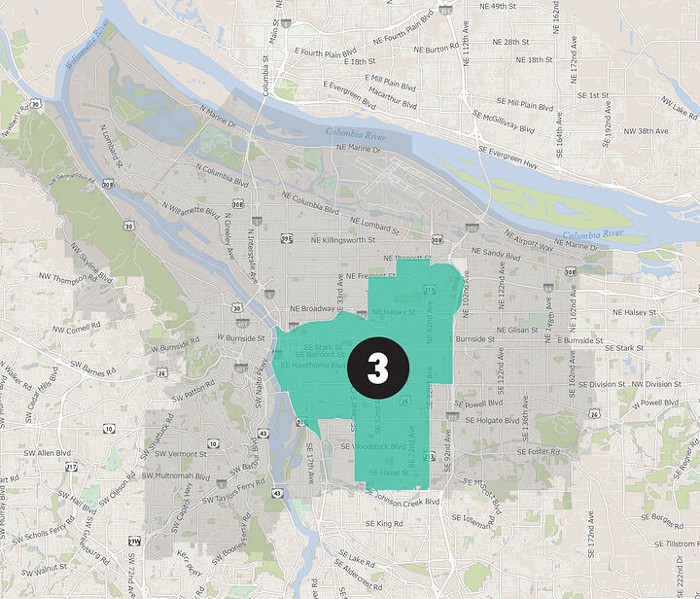

In Zone 3, incumbent Amy Kohnstam is being challenged by retired educator Deb Mayer. (Frequent area candidate Wes Soderback is also vying for this spot, but Soderback’s responses to forum questions and endorsement questionnaires suggest he’s running a less-than-robust campaign.)

And in Zone 7, Methodist minister Eilidh Lowery and former Lents Neighborhood Association board member Robert Schultz are both running to succeed Mike Rosen. (It’s worth noting up top that Schulz blew up and stormed out of an endorsement interview with Willamette Week after asked about rumors that he had ties to far-right organization Proud Boys. Schultz denied those rumors.)

Racial equity

It’s not a stretch to say that PPS has a serious racial equity problem. In January, an audit from the Oregon Secretary of State’s office found that there’s a 53 percent gap in the district between how white and Black students perform on state standardized testing—a significantly larger chasm than the 29 percent gap between white and Black students statewide. There’s also a 36 percent achievement gap between Latino and non-Latino students at PPS.

And PPS’s problems serving students of color extend beyond test scores. A recent public outcry about the board’s controversial decision to start paying the Portland Police Bureau for police officers on campus revealed a failure on the district’s part to engage community members of color on an issue that would likely have a deeper impact on them than their white peers (the board later reversed its decision). A choice to change the year-round schedule at Rosa Parks Elementary, which serves a large low-income population, brought up similar complaints of miscommunication and misplaced priorities.

When asked about how they would work to improve racial equity and close the student achievement gap at a forum hosted by the City Club of Portland two weeks ago, all candidates expressed largely similar ideas: ensuring all district schools teach the same curriculums; prioritizing programs that help students of color in the budgeting process; and setting concrete goalposts for improving racial equity, so that the district administration can be held accountable to them.

“The district is not educating children of color up to their full potential,” said Scott, the Zone 1 candidate. “And we need to make some progress on that, set some metrics and hold the district accountable for achieving those.”

DePass, one of the Zone 2 candidates, called the achievement gap “one of the main reasons I’m running,” and said her work as a board member would include “centering the people whose voices are least heard.”

“In my work with the housing bureau, we use a racial equity lens … so we know the data we use to feed our decisions is centering immigrants, refugees, people of color,” she added.

Clarke, DePass’ opponent, said she wanted to see the district conduct an audit of every language spoken by students’ families, so that every family would have district announcements and resources in their language. Like DePass, she supports moving board meetings to different times and locations so that more people have the opportunity to attend them.

“Not everyone starts at the same starting place, and we need to recognize that and give the proper tools to lift people up,” Clarke said at the forum.

Accountability

Part of a school board member’s job is to hold the district’s administration—and in particular, the superintendent—accountable.

Recent headlines suggest PPS could use an extra dose of accountability over the next four-year school board term. That same January audit found that the district is wildly irresponsible in how it allocates money; a second audit released in April found that PPS’ 2017 $790 construction bond was poorly mismanaged, resulting in a $200 million funding shortfall for projects promised to voters.

Kohnstam, the only incumbent running this year, was tasked with defending that mistake at the City Club forum. She blamed the budget shortfall on “skyrocketing construction costs” and lowball estimates, then made a promise about the bond projects: “There’s no question, the district will deliver.”

Mayer, Kohnstam’s opponent, didn’t let the current board off the hook quite so easily.

“You can ascribe skyrocketing construction costs and other things like that to maybe part of the problem,” she said. “But it seems to me like there’s something else going on here. There must not have been transparency or oversight—the things the board is responsible for. I think we ought to have an investigation.”

Other candidates echoed Mayer’s call for increasing bond oversight of bond projects and other district priorities, and noted that the board has a long way to go to regain public trust.

Budgeting

School funding is a top-line issue in Salem this year, and that extends to Portland Public Schools (PPS), which faces a $17 million budget hole for the upcoming biennium. (A school funding bill passed by the state senate Monday could help alleviate that gap, but it isn’t a silver bullet).

The school board doesn’t have the power to overcome statewide financial issues, but it does decide how the district’s limited resources are spent. Beyond prioritizing racial equity, school board contenders have a few ideas of where they’d like to send budgetary support in the district.

Lowery, the Zone 7 candidate, identified a couple areas where she’d want to see the district commit more resources: arts education and comprehensive sex ed. In fact, a concern about cuts to arts and music classes in the district is what motivated her to run for the board seat.

“When music cuts were made, there were a lot of people in my community who could afford private lessons,” she said. “There are other schools where that is not the economic reality.”

Schultz, Lowery’s opponent, said he’d look for creative ways to alleviate funding limits—like offering academic credits for after-school activities such as a robotics club, so that the district wouldn’t have to pay for as many classroom teachers.

Scott, Zone 1’s lone candidate, touted his experience as a former city budget manager, saying he had the experience and long-term vision necessary to steer the district’s budgeting process.

Ballots have already been sent out for the May 21 election, and this Thursday, May 16, is the last day to mail them back. Those voting after Thursday can use ballot drop boxes placed around the city.

Regardless of election results, several new faces will soon join the PPS board—and it will likely be up to them to solve these old problems.