Jan has spent so many nights sleeping on pavement that the cushion of a thick twin mattress feels foreign.

Standing in her new home—an eight- by 12-foot hexagon-shaped building—she hesitates before spreading a brown blanket over the bed’s crisp sheets. Since moving in over a week ago, Jan has been falling asleep tucked inside her familiar sleeping bag over a thin camping pad. Tonight, she says, she thinks she’ll sleep under the covers.

“It’s the decompressing that gets to a person,” says Jan, 58, who spent the last year sleeping under an Interstate 405 overpass in Northwest Portland, and who asked to be identified only by her first name. “It takes a while to get used to the fact that I’m inside a place—that I have a bed, that I don’t have to keep my eyes open all the time. You gotta learn how to be around people again.”

Jan’s cautious acceptance of her new home is a transition that her neighbors, members of her new community, Kenton Women’s Village, are all familiar with.

The village, a collection of 14 tiny buildings (with enough space for a bed, shelving, and a solar-powered electrical outlet) in a secluded lot just north of Kenton Park, is meant for cis and transgender women transitioning out of homelessness—and the trauma that comes with it. When it opened in June 2017, the village was meant to test the efficacy of a women-only “pop-up” shelter that would serve as a stepping stone between homelessness and permanent housing. The pilot program, backed by both public and private dollars, wasn’t meant to last longer than a year.

But the village has exceeded its founders’ cautious expectations. Of the 23 women who’ve lived in the village, 14 have successfully moved into permanent housing with the help of on-site case workers. All current residents are enrolled in a health insurance plan—allowing many to be treated for chronic health issues—and all have replaced missing or lost identifying documents that have kept them from finding work or applying for housing aid. While four residents have been asked to leave for violating village rules, the Kenton village hasn’t brought with it an uptick in crime in the North Portland neighborhood, nor an influx of other homeless camps in the area.

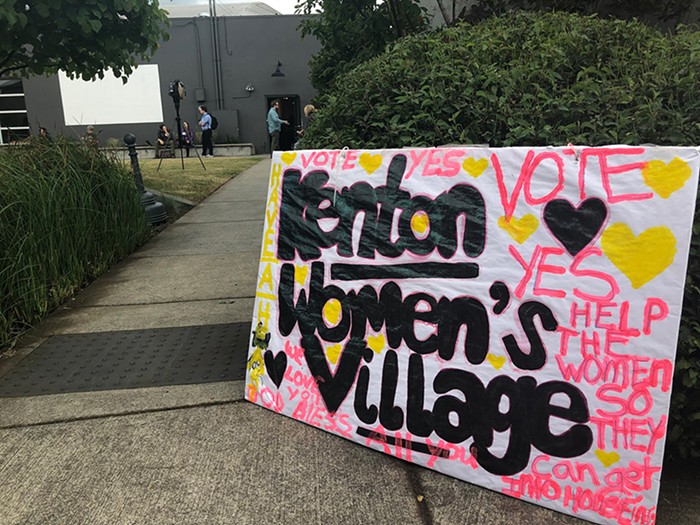

The village’s success has convinced both the city and the Kenton Neighborhood Association (KNA) to allow the village to stay open after its one-year anniversary on June 10. The city has no end date to the village’s lease, and the KNA gave informal approval for a year-long extension in a 119-3 vote on Wednesday, June 13.

But this project doesn’t exist in a vacuum. The Kenton Women’s Village (KWV) sprung up in the midst of a housing crisis felt throughout Portland—and across the entire West Coast—that has given way to a new crop of urban homeless villages built in lieu of affordable housing. Many of Portland’s villages have fallen prey to massive city-directed sweeps, while a number have managed to stay afloat.

KWV, however, is the first intentional homeless community in Portland that had government and neighborhood buy-in from the beginning—and continues to run, in part, on public dollars. Its early success marks a new chapter in Portland’s mission to alleviate homelessness, one that forces politicians to look beyond the traditional models and adopt untraditional, grassroots ideas taken from the housing activist toolkit.

But as the pilot program breezes past its one-year mark, questions remain: What makes the KWV succeed where other transitional camps have failed? What can Portland learn from the KWV, and how can other villages like it fit into Portland’s growing portfolio of homeless solutions?

The idea for the Kenton Women’s Village began about 14 miles southeast of its current home, in the former center of Portland’s homeless community: the Springwater Corridor.

In 2015, the bike-walk corridor was dotted with homeless campsites, a response to then-Mayor Charlie Hales’ “safe sleep guidelines,” which allowed homeless Portlanders to spend the night on sidewalks and certain city lots as long as they abided by certain rules. It was then that homeless advocate Lisa Lake heard from a number of single female campers—some of them victims of domestic violence—that they felt unsafe camping alone. With donated funds, Lake was able to construct six wooden platforms, each topped with a new tent and set aside for women, at Southeast Woodstock and 93rd in May 2016. The camp was taken down by the city the next day—the first of many campsite sweeps that would take place along the Springwater Corridor that summer.

Lake and other members of the Village Coalition, a group of representatives from the region’s various homeless communities, then negotiated with Hales’ office to find a city-sanctioned piece of land to house the women’s village.

The mayor’s office suggested an empty industrial lot on North Argyle Street owned by the Portland Development Commission (now called Prosper Portland). The property had been bookmarked by the housing nonprofit Transition Projects to hold a new low-income housing complex—but the group knew it wouldn’t be able to secure construction funding for at least a year. So Hales married Lake’s women-centric program with another project from the Village Coalition called Partners on Dwelling (POD). POD, made up of local architects and Portland State University design students, had already been given $35,500 in city funds to experiment with prototypes for small, portable structures (called “pods”) for houseless Portlanders.

At the same time, a number of regional governments had approved new agency standards for temporary “pop-up shelters” for people experiencing homelessness—and Multnomah County’s Joint Office on Homeless Solutions was looking for a place to test it out.

In his last month before leaving office, Hales met with the Kenton Neighborhood Association with a pitch: The city would help drop 14 pods onto the vacant industrial lot in Kenton, where the county would run a pilot housing project for homeless women.

On March 8, International Women’s Day, KNA informally approved the village with a 178-75 vote, after ironing out a number of rules with Catholic Charities, the organization plucked by Multnomah County to manage the city-owned property.

By June 10, it was open for business.

“Z-I-R-K-L-E,” says Karen Zirkle to KWV manager Bernadette Stetz, who’s employed by Catholic Charities. Stetz is holding a phone to her ear as she speaks with a rental agency, helping village resident Zirkle apply to live in an apartment complex.

Zirkle, 56, has lived at the village since it opened last year, but hasn’t been interested in moving out until recently. After spending the previous three years living out of her car, she says she needed time to adjust to the possibility of what she calls a “normal life.”

“When you’re homeless, you don’t have time to think about your long-term plans,” Zirkle explains. “You’re thinking about how you’re going to get gas money, how you’re going to get a shower, where you’re going to get your next meal. You’re in a constant state of anxiety.”

Jan, the village’s newest tenant, says she knows of a few people who’ve gone directly from sleeping on the street to living in their own house, without any time to transition. Without guidance, she says, many of them end up homeless again.

After moving into KWV, women are allowed 30 days to recuperate and settle into their new environment. Only after that period of time are they asked to start helping with the village’s upkeep and meet with a case worker to begin planning their next step. Each resident has their own set of goals, says Stetz, and they’re given no deadline to move out.

“When you’re homeless, you don’t have time to think about your long-term plans. You’re in a constant state of anxiety.”—Karen Zirkle, KWV resident

Over the past year, Zirkle’s released her years of stress by managing the village’s garden—a project that’s yielded enough produce to feed both the village’s residents and trade with local food pantries.

“Gardening saved me,” she says. “I needed to be able to nurture something.”

Before moving to KWV, Zirkle says she had mentally “shut down” after a series of tragedies. It began when her boyfriend shot her, forcing her to move into her parent’s house for a year of recovery. When she finally moved into a room in a rental house, the building burned down in a fire, destroying most of her possessions. That’s when she moved into her car.

“It just got harder and harder and harder,” she says. “Then I came here, and I got my self-respect and hope back. I don’t have to struggle to live anymore. I know I’m a survivor.”

Along with help in navigating the housing market, Catholic Charities case workers connect residents to substance abuse treatment programs and mental health care. Stetz says nearly every women who enters the village has mental health needs that have been intensified by their unstable environment.

“They’re carrying a lot of trauma,” Stetz says. “We do everything we can to get the ladies the help they need.”

Mental health isn’t the only condition that’s impacted by years of homelessness. Spending the winter sleeping under the I-405 overpass left Jan with swollen eyes from car exhaust fumes and a bad back from sleeping on the hard pavement.

“It was just tearing me apart,” Jan recalls. Catholic Charities has been able to connect her to a primary care physician to help her with other ailments, like arthritis, glaucoma, and a broken rib.

In their intake process, residents are asked how frequently they go to the emergency room—a fairly common trip for those who can’t afford preventative care. On average, Stetz says, the women had visited the ER around twice a year before moving to Kenton. The bill for each uninsured visit, which can average $2,000, is often footed by the city.

Now that all KWV residents have health insurance, there’s only been one trip to the ER and no ambulance trips.

Jan says her current medical issues have kept her from finding a job. While she originally moved to Portland from North Dakota to take care of her ailing great-aunt, after that woman’s death, Jan slid into homelessness. She’d like to return to a job where she takes care of vulnerable people.

“I’m a caregiver by nature,” she says. “But I want to be able to centralize on taking care of myself for once.”

For Jan, it was her great-aunt’s death. For Zirkle, it was her house fire. For another resident, it was an abusive relationship. And for another, it was an abrupt end to her job. Each woman who enters KWV can pinpoint the exact crisis that left them without a home.

Many who end up homeless lack the support of friends and family who can help when a crisis arises, says Village Coalition co-founder Vahid Brown.

“The secret sauce to these villages is the social infrastructure. That’s the key piece that’s really provided in these communities,” says Brown. “Villages create those safety nets for people going forward.”

That’s how Lisa Larson, a longtime member of Portland’s only other city-sanctioned community for houseless people, Dignity Village, sees her community.

“We become a family,” Larson says with a laugh. “Maybe a dysfunctional family.”

Dignity Village, a nonprofit community that houses up to 60 in tiny homes west of Portland International Airport, was built by activists in 2000. The Portland City Council signed a contract with Dignity Village in 2007, allowing the nonprofit to manage the city-owned property. Larson’s lived with her husband on the property for more than 8 years.

“In your neighborhood, how many people do you truly know?” Larson says. “We all know each other here. If something happens, we’ve got each other’s back.”

There’s a marked difference, however, between Dignity Village and the KWV: While Kenton residents must run community decisions past Catholic Charities, the village manager, Dignity Village is entirely self-governed. Larson says it’s an important distinction.

“For [residents] to not get the final word on decisions... it’s just not fair for them. It affects their self-worth,” she says. “They’re still underneath someone’s thumb.”

Shortly after KWV began operating, Larson met with some of the residents to help them facilitate weekly, self-governed meetings. Any decisions that come from those meetings, however, must be approved by Catholic Charities’ village staff.

“There are some natural leaders in the group,” Larson says. “I believe they could govern themselves.”

There’s another major element to what makes KWV uniquely successful: Unlike other pop-up villages and homeless shelters, it has neighborhood support.

In the past few years, Portland neighborhoods have reacted to homeless villages with immediate disdain; even more formal homeless shelters, such as the one the county has proposed for Southeast Foster, have been met with stiff opposition from neighborhood groups. That’s why so many villages, like Dignity Village and the newly relocated Right 2 Dream Too, have ended up in industrial areas or on property at the outskirts of town. After an initial embrace by the city, North Greeley’s Hazelnut Grove village has faced harsh opposition from the Overlook Neighborhood Association—opposition that inspired Mayor Ted Wheeler to threaten the village’s future last October.

Kenton Neighborhood Association (KNA), meanwhile, has embraced the village. During the Wednesday evening meeting to vote on the future of the village, some area residents teared up watching a video about a village resident who had moved into her own apartment. They cheered when the overwhelming vote to keep the village rolled in.

According to KNA Chair Tyler Roppe, that’s because his neighborhood had an “unprecedented” amount of leeway over the village from the beginning. Not only was the KNA granted a vote by the city—one that could effectively extinguish the entire project—but neighbors were allowed to impose rules on the village that women must agree to before moving in.

Women couldn’t have overnight guests, for instance, and couldn’t make too much noise past a certain hour. No violence, drug use, or open containers of alcohol, either. Another thing he admits helped win neighbor’s approval: That the village was only for women.

“This project really didn’t want to go forward without neighborhood support,” Roppe says. He sees the village as a crucial part of solving the city’s housing crisis—but he’s also concerned that affordable housing options don’t exist for women wanting to move out of the village.

Longtime KWV resident Ruth Lockwood, 57, has felt the reality of that housing gap. She calls herself “not homeless enough,” since she has too many resources to qualify for certain housing programs, yet not enough to reliably afford her own housing. She’s tried to apply for a Housing Choice Voucher (a federal program, formerly known as Section 8, which helps subsidize rent for low-income tenants) to get federal assistance on rent. But in Multnomah County, the high demand for rental assistance has temporarily closed that waiting list. According to a report by Metro, the estimated waiting time to get into a public housing complex in Multnomah County is 14.5 years.

“It’s a letdown,” Lockwood says. “If this village closes, I’ll probably go back to living in my car.”

Roppe says there’s a number of low-income housing projects in the neighborhood that have been put on hold due to lack of federal funding. One of those pending projects is a Transition Projects low-income apartment complex that was expected to replace the KWV by this June. According to Transition Projects Director George Devendorf, that development has been stalled until early 2019.

In the meantime, Roppe wants to know what the city has learned from KWV.

“Originally, this pilot project was supposed to plant a seed for other homeless communities to pop up around the city,” Roppe says. “But I don’t know of any. Wasn’t the city’s purpose to demonstrate it works and then replicate it across other neighborhoods? What’s next here?”

Marc Jolin, director of the county’s Joint Office of Homeless Services, says that question can’t be answered—yet. Catholic Charities is in the midst of its own internal evaluation of the program, and then will meet with the agencies involved to discuss the KWV’s strengths and weaknesses and decide if the model should be replicated elsewhere in Portland.

But, Jolin warns: “This model doesn’t work for everyone. For some people, a large shelter may work better. It’s important we keep serving different people in different ways.”

Kenton fits the exact needs of its residents. Many Kenton tenants say that when they were homeless, they’d rarely opt to spend the night at a large city shelter—the packed rooms only increased their anxiety. But the Kenton model, however, wouldn’t work for families or people with certain disabilities that would make it difficult to access the pods.

Mayor Wheeler, who serves as the head of Portland Housing Bureau, says he’s “awestruck” by the work Catholic Charities and village residents have put into the project. In a statement sent to the Mercury, Wheeler echoes Jolin’s thinking—but doesn’t say if they will be replicated anywhere else.

“As we work to house thousands of our neighbors every year, each traditional shelter, alternative shelter, or housing placement will be different, with a unique set of circumstances to consider,” Wheeler writes.

The city’s lack of clarity about the future of villages like the one in Kenton hasn’t kept other communities from replicating the model. Clackamas County is in the final stages of constructing its own village for homeless veterans; the first 15 residents will live in KWV’s most popular pod model. The village is slated to open by the end of the summer.

Todd Ferry, a fellow at PSU’s Center for Public Interest Design and the head architect behind the POD model, has spent the past year gathering feedback from KWV residents on their unique structures. He says the Clackamas village will reflect lessons learned from the Kenton pilot project, such as better ventilation and increased storage space.

“The first model is never going to be the silver bullet,” Ferry says. He’s also heard from a number of religious organizations interested in hosting their own pod-centric village. Instead of spurring more publicly-backed villages across Portland, Ferry says the KWV may instead act as an example for private organizations, churches, and nonprofits to replicate.

Ferry partially credits KWV’s success to its timing—the POD project was propelled forward with funds made available after Portland declared a housing emergency in October 2015. But he also sees it as a lesson for local agencies who’ve tried to patch the growing housing crisis with outdated, tired solutions.

Or, in his words: “The city’s realizing there’s an inherent wisdom among the houseless community.”

The Kenton Women’s Village is a clear product of Portland’s housing crisis. While it may not be the end-all solution to the region’s skyrocketing rents, the village plays a vital role for some of Portland’s most vulnerable women stuck in the debilitating cycle of houselessness.

Before the Wednesday KNA vote, Jan leans on her cane near the front door, sipping on seltzer and chatting with Kenton neighbors who’ve stopped by.

“Thanks for voting!” she calls out as people drop their ballots. She smiles, looking out at the crowd, and inhales. Asked how she’s feeling, Jan replies: “Good. You know what—I finally got a good night’s sleep.”