The Sub Pop collection reprises Springsteen's classic 1982 album with interpretations by, among others, Ben Harper, Aimee Mann and Michael Penn, Los Lobos, Son Volt, and Crooked Fingers. It is sequenced in the original running order, with three extra songs added that were written during the Nebraska sessions but released on later albums (Johnny Cash sings "I'm On Fire"), yet the album is essentially over when Nebraska's 10 songs end--its dark vision is so complete.

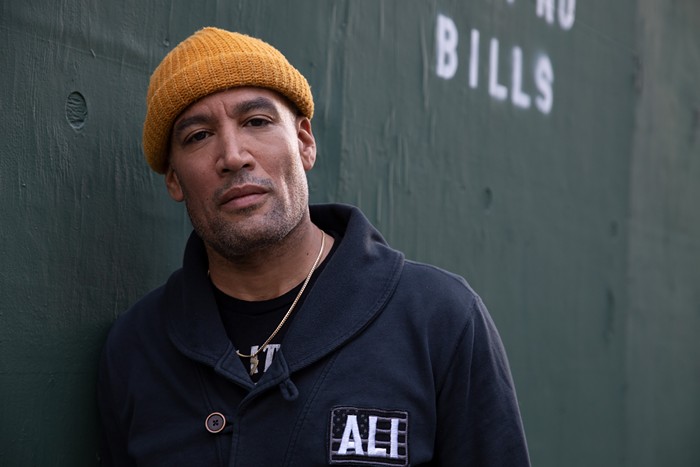

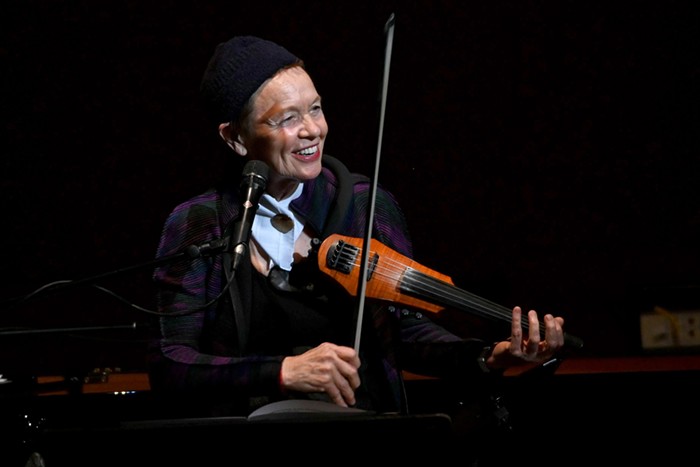

Badlands demonstrates the strength of the material. The artists who hew closest to the source material deliver the most satisfying performances. Chrissie Hynde nails Starkweather's cold-blooded candor perfectly on "Nebraska." Ben Harper wraps his gorgeous, quavery voice around "My Father's House," and devoid of her usual self-importance, Ani DiFranco fills "Used Cars" with a desiccated ache.

Badlands serves Nebraska's greatness well, but it raises the question of where this kind of subtly integrated, sociopolitical songcraft has gone, and why there is no equivalent today. Nebraska was Springsteen's sixth album. Following 1980's hugely successful album The River, Nebraska, recorded on a four-track in his home with just acoustic guitar and harmonica, audaciously took the feel-good boys of 1975's "Born to Run", and heaped years of disappointment, layoffs, and lost ideals on them: He had let Reagan's "National Renewal" take its toll on them as it had the rest of the country. It was the embodiment of dispossession.

It seems impossible to imagine a popular artist today on a similar career trajectory taking a risk like that, being that honest. Not the angry, flailing, or stage-managed bombast we are sold as political, but real outrage, the kind that drains the heat from you, that requires listening and modesty.

Beyond craft, what has made Nebraska stand as a great album is that there is no phony uplift. Springsteen does not try to sugar the pill. At the time, many critics read the last song, "Reason to Believe," as their hero's reassurance, an affirmation of hope. But the chorus--"at the end of every hard-earned day, people find some reason to believe"--comes on the heels of a verse about a man on Highway 31, poking a dead dog with a stick "like if he stood there long enough that dog'd get up and run." The reason to believe is a man prodding a corpse.

In this self-satisfied, benumbed cultural moment, it seems far beyond our current songwriters to write so unsparingly about class as Springsteen did on Nebraska. The rebellions on Nebraska are murders, the nihilism of desperate people. The men in these songs address prison guards, judges, and authority figures--people who measure all things, and always tell them they have fallen short. These are men who have grown up in the shadow of the mansion on the hill, watching their factory and mill worker fathers patronized by used car salesmen and discarded once their economic functions have been exhausted. This is not about the kind of angst or alienation rock and roll usually taps into. These are men exiled from their country, from their culture, and from themselves. On "Johnny 99" a man loses everything, gets drunk, shoots and kills a clerk, is sentenced to life, and begs the judge for death. A single life and a nation's life are delineated in the space of a few minutes.

Nebraska says all that. It calls out the lies of the political fantasies we re-enact, the script we cling to even as the psychic geography is redrawn under us, as the epistemology of how we live and die is rewritten into law. Is there someone who can capture this moment when we seem to have confused freedom with having the choice of 15 kinds of coffee and five different ways to get email? Is there a songwriter out there brave enough to tell our stories now? Someone whose personal and political is so hopelessly and beautifully mixed up that they have no choice but to tell the truth?