"IT MAKES ME MAD," Willis Earl Beal says of the swooning media's attraction to his backstory over the substance of his art. "It makes me real mad." That backstory, in short, paints Beal in somewhat sensational strokes as an unstable outsider and weirdo drifter.

It began with a hand-drawn self-portrait bearing his phone number posted around Albuquerque with a sweet note beckoning "pretty girls" to call. The poster made its way to the cover of Found magazine. An intriguing profile in the Chicago Reader followed, with tales of odd jobs, a military discharge, homelessness, leaving CDs of music around Albuquerque, and busking on train platforms in Chicago. A subsidiary of XL records signed Beal to a multi-album deal.

The first, Acousmatic Sorcery, is a collection of songs pulled from taped demos, sketches, and experiments. It is clattering, thin, out of tune, sharp, and rusty. Underneath the hiss, however, is a lilting, beautiful, endearingly honest window. Beal delivers existential streams of consciousness, weaving love, dreams, struggles, questions, survival, and insecurity.

Aside from his plucky, simple, and flubbed guitar and pointy pot-clanging percussion, Acousmatic is carried by Beal's rich and malleable voice. He howls and yelps, plumbs the blues, hints at gospel, soul, rap, and soft, breathy tenderness. Its pretty and melancholic songs are, to borrow a line from Beal's own "Bright Copper Noon," like "lullabies slightly out of tune."

"Acousmatic Sorcery was, for me, just a novelty," Beal explains. "It was a thing I was doing for myself and I wanted a couple of local weirdos to hear. But the fact that it's out there en masse now is kind of an embarrassment to me." Eventually he hopes to re-record the songs in a proper studio.

Nonetheless, the lo-fi nature of the recordings, coupled with the notion of Beal as oddball outsider, have drawn comparisons to Daniel Johnston and Wesley Willis. I find the suggestions perverse, wrongheaded, and insensitive. Beal may be odd, but to suggest kinship with those suffering profound mental illness crosses the line. Instead of some myth or mystery, I found Beal grounded—an open book.

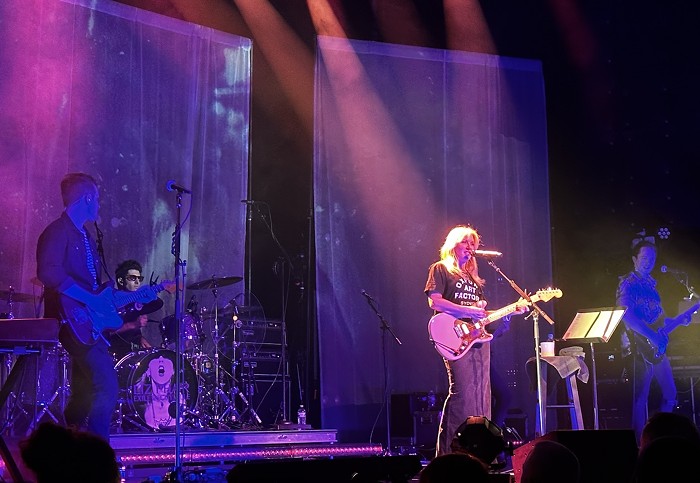

Live, he performs alone. A tape machine plays backing tracks, which have been re-interpreted. "They are songs that are on the record but fully realized," he says. "The way I wanted them to be heard."

The tape machine's purpose is twofold. "I don't really collaborate well with other people," Beal says. "I feel overshadowed by other musicians so I prefer to be alone. On top of that, I'm not a good enough live instrumentalist to play live instruments every single time."

Free from playing, Beal's voice and personality take over with a force and power wholly absent from the record. "It's like a lounge performance," he says. "It's kind of a spoken-word thing. It's also a concert and it's also intimate... it's almost performance art." Hopefully, he says, it'll be enough to overcome the surrounding narrative.

"I'm doing this thing for the thing to stand on its own," Beal explains. "It's getting a little redundant because I do consider what I do—what I actually do—to have substance. And people keep talking to me about what happened to me in my life and this kind of thing, then I feel like I could just quit, really, and they could just pay me to tell my story.

"You don't have to like it," Beal continues. "Just look at it. Think some thoughts and move along, you know? That's all anybody wants, is to be heard. That's all."