BEING A NEIL YOUNG FAN has never been easy. The mercurial musician follows each of his whims to its bitter end, and the result is an unstable but fascinating career that's contained more zigs and zags than the edges of the Aztec pyramids he dreamily sung about in "Cortez the Killer." But in the past couple of years, Young—who has always been impassioned—has allowed his art, once so supremely abstract and fluid, to turn didactic and hectoring.

His latest album is called The Monsanto Years, and in case you weren't paying attention, Young really, really, really, really doesn't like GMOs. This is a cozy, feel-good stance for Young's staunchly liberal fanbase, although the discussion is miles more complicated than he lets on. For instance, diabetics rely on synthetic insulin—a genetically modified agent if there ever was one—to survive; Forbes awkwardly pointed out that Young himself is a Type 1 diabetic. The Monsanto Years ignores such subtleties, but worse, it doesn't really point to any solutions, instead choosing to grumble for 50 minutes about a lot more than GMOs, including Starbucks, oil drilling in Canada, big box stores, and more. With gentrification, displacement, and city planning as the current bugaboos of an overcrowded America (especially near Young's longtime home in the Bay Area), The Monsanto Years' agricultural screeds feel like time-stamped laments from a slightly bygone era.

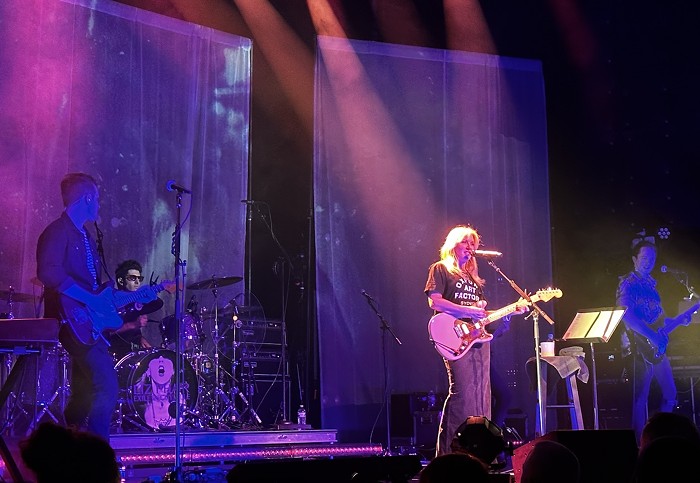

The good news is that the new album contains glimmers of fine rock 'n' roll amid the spittle-flecked fury. Working with Promise of the Real—a band that contains Willie Nelson's two sons, Micah and Lukas—Young's lumbering country-grunge sounds lighter and fresher than it has in years. It's a welcome change from his problematic past few albums, where Young's reliance on a musical stable of gray-haired sidemen resulted in some very tired-sounding music. Even his longtime cohorts in Crazy Horse, his best backing band, were saddled with incoherent songs in 2012's Psychedelic Pill. (For a glimmer of what that album should have been, listen to "Ramada Inn," then put on Side Two of Rust Never Sleeps and never ever listen to the rest of Psychedelic Pill.)

Perhaps due to its cast of younger, fresher musicians, The Monsanto Years has some great moments alongside its clunky ones. "A New Day for Love" starts righteously, with a chunky power-chord riff and Young's dangerbird guitar piercing through the thicket of sound. The melody, though, wanders witlessly as Young raps ungainly stream-of-consciousness images. "Wolf Moon," meanwhile, is a delicate folksy ballad in the lunar vein of "Harvest Moon," with Young reaching into the painful upper registers of a tenor that characterized albums like After the Gold Rush. Young's voice, once so wonderfully naïve-sounding, is a lot less elastic now, and his sweet gingham melody trails off at the end of each verse rather than finding resolution. The biggest firepower from the ensemble comes on "Big Box," a song that, while sloppily thought out, holds hints of the wonderful thumbnail character studies that Young used in his 1988 stage masterpiece "Ordinary People" (which didn't see release until 2007 in a halting, inferior studio version).

Like much of his output, finding the good moments in The Monsanto Years is like panning for gold. This is nothing new for fans who've scoured albums like Landing on Water and Greendale in search of magic (hint: try "Touch the Night" and "Bandit"). But the strengths of Young's new music have been sidelined by his high profile in the media. He's only a few weeks shy of his 70th birthday, but in the past year, Young has commanded as many headlines as pop stars a third his age. Most surprisingly to longtime observers, Young split from his wife of 36 years, Pegi, and took up with movie star/activist Daryl Hannah, a coupling that just seems... weird. As a result of the breakup with his wife, Young feuded with his longtime musical partner David Crosby in an ugly, public way. Additionally, Young took Donald Trump to task for using "Rockin' in the Free World" in a campaign appearance; Trump retaliated by accusing Young of asking for money to fund his controversial Pono project and posting a photo of the two together, smiling. (Do we have room here to talk about Pono and Young's bizarre obsession with high-resolution digital audio? I'm sorry, my editor's shaking his head.)

There's plenty more for seasoned Neil Young fans to gripe about: The unjustly high cost of his albums on vinyl. The seeming abandonment of his career-spanning Archives project. The fact that one of his darkest, most rewarding albums, 1973's Time Fades Away, remains out of print. And on and on.

But even as I write this, I see an online news post that Young and Promise of the Real pulled out an old chestnut for their Seattle show earlier this week. "Here We Are in the Years," a pastoral folk-rock mini-suite of goldenrod perfection from Young's 1968 self-titled album, has made an appearance in the current setlist—the first time he's trotted it out in concert since 1976. And I'm back in the throes of fandom once again, as excited as I've ever been for the opportunity this week to see Young do it for real. With Young, the good and the bad coexist, often inseparably. And when the unchecked passion that fuels ineffective broadsides like "A Rock Star Bucks a Coffee Shop" also gives us gorgeous work like "Winterlong," "Cowgirl in the Sand" and "Thrasher," well, that's a price I guess I'm willing to keep paying.