The first six months of the Portland Street Response pilot project is meeting its lofty expectations, according to a Portland State University (PSU) study released Tuesday.

"Based on the findings... we feel very optimistic about the future of Portland Street Response and believe it is well on its way to becoming a citywide solution to responding to 911 and non-emergency calls involving unhoused people and people experiencing mental health crisis," reads the report, conducted by PSU's Homelessness Research and Action Collaborative.

The Portland Street Response (PSR) is an unarmed first responder team comprised of a mental health clinician, firefighter paramedic, and two community health workers who are dispatched to 911 calls regarding mental health crises or issues regarding unhoused people. The program was created in 2019 as a way to both lessen the workload of the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) and to steer people in need toward social services and health care instead of the criminal justice system. The pilot, which focused on responding to calls originating in the Lents neighborhood, was meant to begin in 2020—but a city hiring freeze caused by the COVID-19 pandemic delayed the project by a year. The year-long pilot began operating in February 2021. A six-month evaluation of the program by PSU was written into the program's plan, and will serve an integral role in city commissioners' decision to continue the burgeoning program.

The study drops as Portland City Council holds a work session Tuesday morning with PSR staff to get an update on the program's first six months in operation. (Tune in to that work session here at 9:30 am).

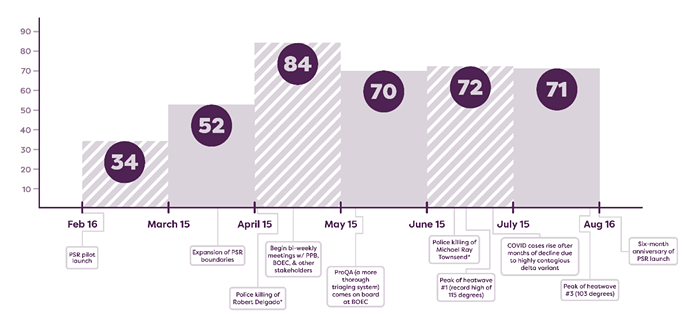

Researchers found that PSR responded to 383 incidents between February 16 and August 16, with the vast majority of them (344) being situations that PPB officers would normally be called to respond to. The report calculates that the team's work reduced the number of police responses in Lents by nearly 5 percent. PSR also responded to a sliver of 911 calls that would traditionally be handled by Portland Fire & Rescue, like reports about homeless camp fires or heat-related health concerns.

The majority of the 911 calls handled by the PSR team during that time frame that are usually dealt with by a PPB officer were characterized as "welfare checks" (for instance, concerns about a person passed out on the sidewalk or yelling in the middle of a busy street) or "unwanted persons" (like a call from a business owner who can't convince a person to move out of a store entryway).

"The vast majority of PSR calls were resolved in the field, with no need to transport people to the hospital for... high-cost emergency services."

Just under 4 percent of all PSR calls resulted in a person needing to be taken to the hospital, a statistic that the report cautiously celebrates. "The vast majority of PSR calls were resolved in the field, with no need to transport people to the hospital for... high-cost emergency services," it reads. Instead, the PSR team treated wounds and checked vital signs on the ground, along with providing emergency medication (like the overdose-reverser Narcan) and de-escalating people in mental health crises.

The most common outcome of calls routed to PSR, however, is less optimistic. According to the report, one-third of all calls were either cancelled prior to PSR's arrival on the scene or resulted in PSR staff not being able to locate the subject of a call. In several instances, the calls' subject refused PSR's assistance.

"This reflects the difficult nature of the calls PSR responds to," the report reads. "In many cases, others have called to request service for the person they believe is in crisis, and this person may not wish to interact with first responders, or may have moved away from the initial location."

The second most common outcome of a PSR response: A subject of a call was evaluated by the team and didn't require any further treatment. None of the calls resulted in a person being placed under arrest.

The populations PSR responded to most are in line with the program's mission. At least 67 percent of all individuals PSR was called to assist were unhoused and 52 percent had "suspected mental health needs." Many of those treated by PSR received follow-up assistance from PSR's community health workers, connecting people with social services, financial support, health care, or housing help. A total of six people PSR were called to respond to obtained permanent housing through PSR's help.

Researchers interviewed several of the individuals who had been aided by PSR, and asked how the experience compared to their past interactions with other first responders.

“It was way less restraining," one person, quoted in the report, told them. "Police are rude—tell you what to do. You can’t treat people with animosity because then they’ll defy it—like an authority figure. I have PTSD, and that doesn’t work for me.”

Others described PSR staff as compassionate, calm, and sympathetic to their needs. They explained to researchers that PSR health workers helped them fill out paperwork to get into housing, gave them blankets, and treated them with respect.

The study identifies several issues that could hamper PSR's future success. One is the group's current limitations regarding which types of emergency calls they can be dispatched to. PSR's framework prohibits staff from responding to calls involving weapons, where a person is threatening violence, or where a person may be suicidal. Another is the group's limited working hours. Currently, PSR currently operates between Monday to Friday from 10 am to 6 pm.

These are the reasons why, when neighbors called 911 at 9:30 am on April 16 to report that a man who appeared homeless was playing with a gun in Lents Park, PSR did not respond to the scene. One of the Portland officers who did respond ended up fatally shooting the subject of the call, a man named Robert Delgado.

PSU researchers note that these types of calls—at the intersection of mental health, homelessness, and crime—are where PSR's "skills are potentially needed most." According to the report, PSR is prohibited from responding to calls regarding suicide due to a past contract agreement with the Portland Police Association, the union representing rank and file PPB officers. This rule could be adjusted by the city negotiating a new agreement with the police union over who can respond to suicide calls.

PPB does partner with another unarmed mental health response team, called Project Respond, when it receives calls related to suicide or mental health crises involving weapons. Yet the appearance of Project Respond clinicians working side-by-side with armed law enforcement has drawn criticism from local leaders, who say the partnership could reduce the public's trust in the program or cause reluctance in others to seek help. In many ways, PSR was created in a response to that critique, as a group that didn't rely on police backup to help people in crisis.

PSR received additional funding in June 2020—in the midst of the city's racial justice protests—in a city budget vote that focused on diverting money away from the police and into alternative solutions.

“At the end of the day, if we care about results, one of us is going to have to make a concession and sort of do the work to try to bridge the gap.”

Possible problems with that intention is also captured in the PSU report. Through focus group interviews with PPB officers regarding their perception of PSR, researchers found that many police aren't sure what their relationship with PSR is expected to be.

The report quotes one PPB officer saying, “...it seems like PSR doesn’t want anything to do with us. I don’t know if it’s adversarial or they just don’t want anything to do with us, but there could have been a whole lot more communication... We’re supposed to work together, and it doesn’t appear that’s the way it’s going to work.”

And, another officer: “At the end of the day, if we care about results, one of us is going to have to make a concession and sort of do the work to try to bridge the gap.”

PSR staff, meanwhile, told researchers that they are interested in working with police to make sure they're on the same page with individuals who are frequently reported to 911, and to step in on mental health or homelessness related incidents when police no longer think that there's a threat of violence.

PSR members pointed to other limitations in their work, specifically around the lack of resources for Portlanders in crisis.

“The lack of services for acute mental health needs (besides the hospital) and substance use services/detox/sobering center gets overwhelming when you feel like you don’t have the right resource to offer the individual in need," one PSR employee told researchers. Another staffer said PSR's work felt like a "band-aid" to a much more systemic problem.

PSR was again brought into the city's budget talks this year, when it was only two months into its pilot program. In question was the use of the $4.8 million the city had put in a reserve for PSR in June 2020. While City Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty, whose office oversees PSR, had asked for the majority of those funds to be released to allow the pilot to expand to a citywide program after its first year, the majority of City Council blocked all but $1 million from going forward, arguing that commissioners needed to see more data on the program's success before releasing more money. The conflict over the efficacy of a brand-new program that, for some progressives, is considered a potential, future replacement for the entire PPB, has placed pressure on those already doing the pilot work.

One PSR staffer is quoted in the study admitting that, “Most of my stress related to the job has more to do with the politics surrounding the program and how high profile it is.”

The PSU study should answer some of the questions regarding data that city commissioners yearned for earlier this year—and will help inform another fast-approaching budget request to sustain the program. Portland Fire & Rescue has submitted a budget request for council to consider during the upcoming fall budget monitoring process (or, "Fall BMP") that would steer $1 million into PSR and allow the program to expand citywide by March 2022 and to operate seven days a week with new hours.

“Most of my stress related to the job has more to do with the politics surrounding the program and how high profile it is.”

The proposed budget funds would allow PSR to hire 13 new full-time employees and purchase more vehicles to respond to calls from Monday through Thursday between 8 am and 6 pm and Thursday through Sunday between 5:30 pm and 3:30 am. This budget item will be discussed during a separate City Council work session later this month.

In a press statement, Hardesty acknowledged the role this report will play in upcoming council budget talks.

“PSU’s 6-month evaluation report includes vital information to understanding PSR’s success and where it can improve moving forward," said Hardesty. "I’m so thankful to everyone at PSU for this extensive work that will help inform Council as it prepares to vote on expanding PSR citywide this October.”

The PSU study offers a number of recommendations to City Council based on its analysis, with one leading the rest.

"It will come as no surprise based on the findings of our evaluation that our primary recommendation is to commit the necessary resources toward the expansion of Portland Street Response to make its services available throughout the city and at all hours of the day," the report reads.

Aside from urging expansion, researchers advise commissioners to expand the variety of emergency calls to which PSR can respond to also include suicide and situations involving people who are inside a residence (this is currently forbidden, again due to a policy agreement with the police union). The report also urges the city to invest more in educating both the public and other first responders about the role PSR plays.

The future expansion of PSR now rests with City Council, which will give feedback during this morning's council session and vote on additional budget funds later this month. PSU researchers will continue to evaluate the pilot program's efficacy as it finishes its first year.

PSR's strongest supporters may be those who've been treated by the team.

"The team has helped me," said one individual aided by PSR who spoke to researchers. "I want it to continue helping people, and not end with me. It should be expanded to help more people. Without it, I wouldn’t be where I am.”