IT'S NOT RIGHT to say that Babes in Toyland were one of the best female bands of the '90s. Babes in Toyland were one of the best bands of the '90s. Period. And nearly three decades after the trio formed in Minneapolis, they're just as important—not only to women, but to anyone who remains true to the DIY approach to making art.

The band's reach is wide—women, men, the disenfranchised—and with its members now in their 50s, Babes in Toyland are influencing a third generation. Drummer Lori Barbero knows full well that the music industry is still a boys' club, but the band's recent performance at Spain's Primavera Sound festival gave her a little faith. "The first five rows were women—that was a delicious fucking sandwich!" she says, laughing. "If we can change someone's life, no matter the gender, it's all worth it."

A few days earlier, guitarist/vocalist Kat Bjelland tells me she's received letters that'll make you want to cry, explaining that she's grown more comfortable with the idea of being a hero to someone, even if it still hasn't quite sunk in. "People tell me that," Bjelland says. "If I am, I hope I'm an okay one."

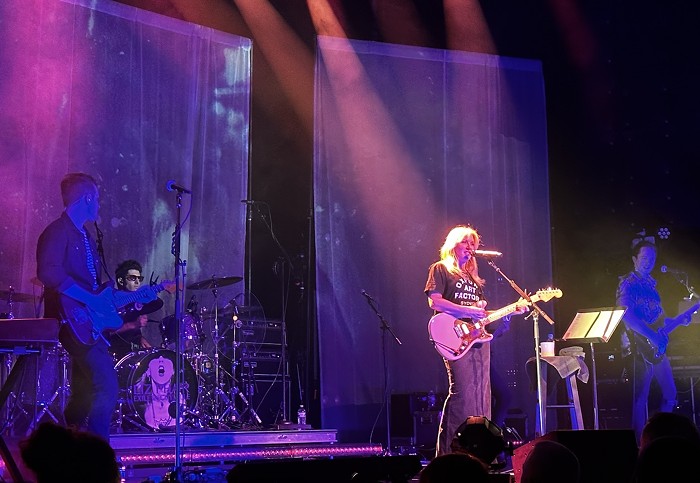

Her answers to my questions are short—thoughtful, but short. Bjelland doesn't do many interviews these days, but she's definitely glad to be playing music again, especially with Barbero. (Bassist Maureen Herman exited the reunited lineup last week; Whatever Forever's Clara Salyer has replaced her.) The return of Babes in Toyland is the result of a couple of factors, one being the oft-reported fact that three former Google employees bankrolled the tour. This is true, but it wasn't a handout. The members are paying it all back through touring revenue.

The main reason for reforming Babes in Toyland goes back to why they started the band in the first place, back in Minneapolis in 1987. Barbero and Bjelland say rekindling their friendship has been a massive positive in their lives. "Eighteen years in a band together is amazing," says Barbero. "It's a relationship—we were under the same roof for a long time."

Late last year Barbero moved back to Minneapolis, where Bjelland has lived for decades. The city had been kind to both of them. Barbero was a fixture in the music scene, working at punk-rock epicenter the Longhorn for years. And Minneapolis is where Bjelland eventually found her punk-rock calling after growing up in nearby Woodburn, Oregon, listening to metal and playing in her uncle's band, the Neurotics.

Around the time Babes in Toyland released their 1990 debut, Spanking Machine, labels were catching on to emerging bands like Bratmobile, Bikini Kill, and L7, but at the start, Babes in Toyland simply considered themselves a punk band. The scene evolved quickly, though; tags like "riot grrrl" began to define the music a bit more narrowly, often putting primary focus on gender as opposed to the music. Things have changed since, though there's still a long way to go. (For evidence, look no further than the title of Babes in Toyland champion Jessica Hopper's anthology, The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic.)

After their 2001 breakup, a reunited Babes in Toyland began rehearsing in Los Angeles last year. Barbero says that the first song they played in rehearsal, "Jungle Train," was also the first song she and Bjelland wrote together back in 1987. The members seemed surprised by how easily everything came back. Not surprising, however, is how well their music holds up, lyrically and otherwise.

The songs still have a profound effect on Bjelland. And there's no doubt they're still affecting listeners with the same intensity. "I like all of the songs," she says. "It's therapy for me. When I stop playing music, it's like a 16-wheeler going 150 MPH into a brick wall."