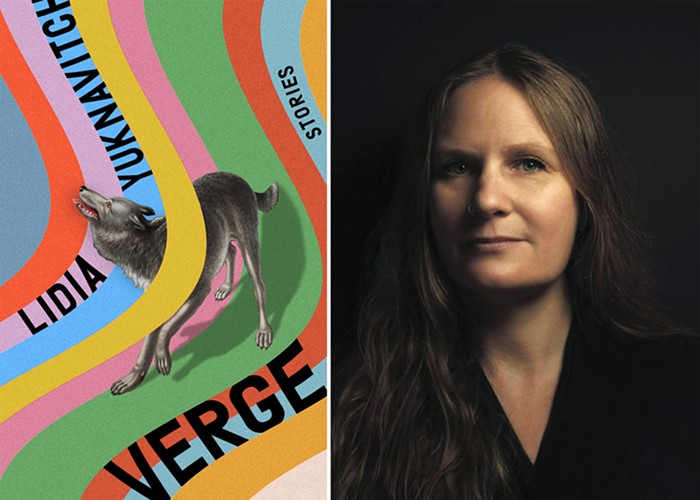

Lidia Yuknavitch is a creative force in Portland’s literary scene. Not only are her books award-winning best sellers, but they’re often groundbreaking, like her Oregon Book Award-winning anti-memoir The Chronology of Water, or her novel The Small Backs of Children in which she strove to break the novel’s form. To discuss her new short story collection Verge, Yuknavitch invited me to Corporeal Writing—a downtown space she uses to teach classes and host readings—which is named for an approach to writing that draws heavily on the body’s reactions and sensations. When I asked about her ongoing plans for the space, Yuknavitch mentioned she wasn’t trying to go too big. Which led me to ask the following:

PORTLAND MERCURY: You don’t want to go too big and flame out? Isn’t that kind of the antithesis of your writing style, which is: Go big and flame out?

LIDIA YUKNAVITCH: Flame up! As often as possible! Verge is certainly a whole book of big flame. These stories are all catching a character on the edge of something. They’re either gonna make the worst choice ever or the best choice ever. Change or grow or die. And they’re vibrating. All the times in my life when I was about to do something that was either gonna blow up my world or bring something great, I felt a vibration.

Verge is a collection of fiction stories, but some feel drawn from your life in ways that remind me of anti-memoir.

I am in the boat of people who see a very thin membrane between fiction and nonfiction.

Could you refresh us on the anti-memoir term? You have your own definition.

Chronology of Water broke all the rules of memoir writing that I had been taught, like “Maintain an authoritative and singular voice.” It broke off and did all sorts of inconsistent things. I wasn’t supposed to let the intensity of an image or an emotion subordinate plot, but I did. This is true in life, too. Whenever someone tells me, “Lidia, you can’t do that,” my response is always to double down.

“Whenever someone tells me, ‘Lidia, you can’t do that,’ my response is always to double down.” -Lidia Yuknavitch

Maybe your fiction reads like memoir still because it has such strong nuggets of your own life. And you’ve been so open with your past experiences that we can see the connections a little more clearly. In Verge’s first story, we can see you pulling from your experiences as a competitive swimmer, and an archetype of heroic sisters. But then you mold it into a narrative about the refugee experience. Can you talk a little about what inspired that?

It came from more than one place. One place was the experience of nationless athletes and the Olympics. I have friends who are those people, runners and swimmers. So some of it is an homage to them. Another place is, sometimes when I’m writing a story that has a little bit of magic in it, I’m trying to write new archetypes about girls. And it’s not even subtle. If I could, I would redesign the night sky with constellations of just women-related things. The third place is my life. The thing where one sister touches the other’s ear? That’s something my sister did. She would play with my ears to get me to take a nap.

What story in Verge is closest to your life?

There are a handful that are about a woman getting ready to do something, “A Woman Refusing,” “A Woman Apologizing.” I feel pretty close to those. As someone who has been married three times and been in three long relationships with women, I feel very close to some of those.

Do you feel like the one, “A Woman Signifying”—

I knew you were gonna ask me about that one!

Because the end has this Carrie Underwood “Before He Cheats” kind of rhythm to it, like when you write “By the time he gets home, she’ll be out already... By the time he gets home, she’ll be sitting at the bar with the most perfect wound imaginable.”

Bingo. It’s not intentional. But I meant to go to a similar place. A lot of people have different readings on that one. I’ve heard it reads as self-harm, and I completely understand how a reader would think that. But my intention was that she’s burning herself to make a second vagina.

“My intention was that she’s burning herself to make a second vagina." -Lidia Yuknavitch

Oh! Wow.

The feeling is, “You’re gonna treat me like I’m a fucking hole? I’m gonna wear the hole on my fucking face.”

Which reminds me, larger publishers used to ask you to take out the word “cunt.”

And they wanted me to remove incest stuff. Implications of sexual abuse from my father. And overt sexual stuff and violent stuff.

And that’s famously why you went with Hawthorne Books for Chronology of Water. But now are you at a level where bigger houses don’t ask that of you anymore?

I fucking hope so.

Verge is published by Riverhead, and they’re a Penguin imprint, so it’s nice that it can still have a lot of sex in there. There’s a lot of really nice sex in there.

It could be the way you put it, and I’ve gotten to a place where they’ll let me. Plus, I have a lineage of identifiable writers I’ve followed and learned from—Kathy Acker was one of my mentors—so I can say, “What about these people?” That’s probably helped. I don’t mean to aggrandize myself, but this is a feature of my personality. You can tell me no, but that doesn’t mean I’ll quit and go away.

With art, boundaries are meant to be broken. But does that attitude carry over to your personal interactions?

Yes, well. I have a string of disasters behind me.