A pre-recorded announcement played before the beginning of when we were Ocean, offering a message of encouragement. There was no wrong place to look, they said. There was going to be a lot to see, after all.

As the new production from local arts group ProLab Dance was being performed at OMSI’s Kendall Planetarium, the message seemed pitched to welcome a number of children in attendance on opening night—including a five-month-old baby, in my row, who focused on the array of dancers in colored jumpsuits with a blend of bewilderment and delight.

Really, the recording was likely intended to take tension out of the shoulders of ticket holders, encouraging us to accept the inevitable conflict of three performances happening all at once: the body-bending action taking place physically, the colorful weirdness going on across the planetarium ceiling, and the set from musician Jennifer Wright—who employed LED-lit plastic sticks to tap on an array of scrap metal dangling tastefully from rack. The last was the infant's favorite.

With a multimedia performance like Ocean, how much is too much? ProLab director and choreographer Laura Cannon packed the hour-plus performance with ideas and incident, all of it formed around a core theme of the Marie Howe poem that gave the piece its name.

Dedicated to astrophysicist Stephen Hawking, Howe’s verses question what the molecules in our bodies might remember about our world before we destroyed it, or before we destroyed ourselves via tightly held constructs of gender, race, and class.

ProLab's adaptation—if we can call it that—presents these concepts quite literally. At one point, Cannon balanced herself within a plastic bowl filled with ping-pong balls; images of the dancers above us slowly morphed into masses of color and shadow.

Much of the projections had been filmed at the Barge Building at Zidell Yards, where ProLab staged their Break to Build performance last June—and where they're planning an encore of it this summer.

The sheer amount of information that Cannon and her team threw at us throughout Ocean had an effect of mushing the dance, the music, and the visuals into bright and colorful memory paste. Within the mind's eye, the movements lost unique definition.

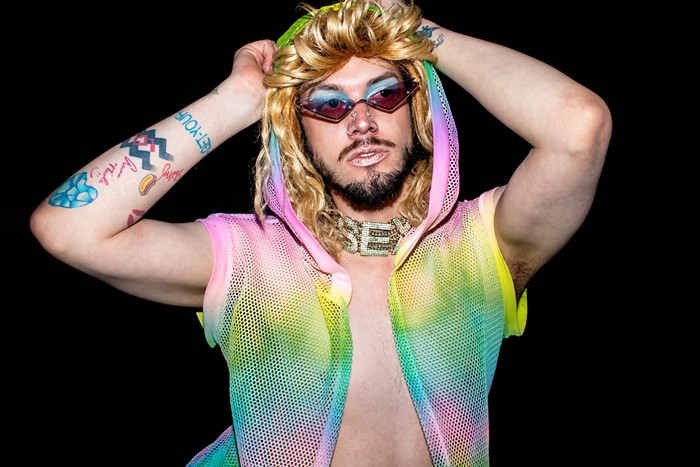

However, there were certainly moments that popped. The opening segment played like an extension of Break to Build: Four dancers performed on and around a large wooden spool, moving with a great deal of body control and mutual support to ensure they didn’t go flying off into the laps of the folks seated nearby. At the culmination, vocalist Bevin Victoria sang a gorgeous ballad atop the spool—while the dancers spun it, like a turntable, with their feet.

Later, two audience members were chosen by lottery to be seated in cushioned wheelchairs, wear Oculus headsets, and be slowly rolled into the center of the room by two dancers. Watching it unfold felt alienating. What could they see that we couldn’t? What effect would the headset view have had on our overall appreciation of Ocean or the messages that Cannon was hoping to impart?

As the introductory announcement predicted, my attention wandered. Yes, to the performers and the piece, but also to the reactions of the audience.

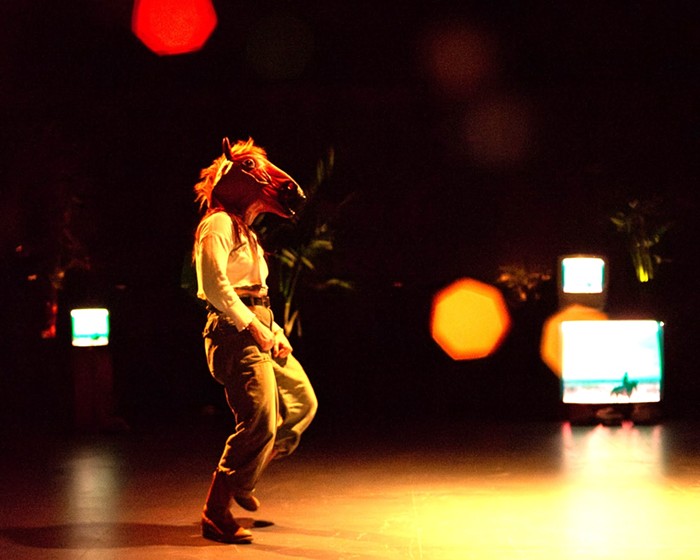

Behind me, a child giggled madly—sharing in my delight—at the multiple images of Cannon and another dancer, superimposed to psychedelic effect and mugging for the camera outside the planetarium. We were also aligned in our flagging interest during a lovely, but slow middle section (which featured the headsets) where the dancers, now costumed in flowing beige, joined their bodies together in a tangle of limbs. I became lost in my thoughts. The youth had a small (but audible) tantrum.

The most damning critique came from an older gentleman seated further behind. Even as I pondered and the child quietly raged, he began snoring loudly, lulled into sleep.