Angela Boyd was creative. After moving to Oregon from California in her childhood, she went on to study journalism and communications at the University of Oregon, where she earned a bachelor's degree in journalism, with an emphasis in advertising, marketing, and fine and applied arts.

Later, she honed her craft and became a sought-after wardrobe and photo stylist. But somewhere along the way, her family says she lost employment and her livelihood, and became homeless, staying primarily in Portland's Sellwood neighborhood.

In April 2022, Boyd was killed by a hit-and-run driver on Powell Boulevard. She was just 47 at the time.

Boyd's story, like many others, highlights the tragic and often complicated lives of those living on the streets, many of whom die long before their time.

Deaths of homeless residents in Multnomah County increased 29 percent per year from 2018 to 2022, according to medical examiner data.

The latest data from Multnomah County’s annual Domicile Unknown report shows at least 315 people died in 2022 while homeless–a staggering increase from the 193 deaths reported to have occurred in 2021.

Of those who died homeless in 2022, 36 percent, or 113 people, died outdoors. Multnomah County had around 5,230 unhoused people that year, according to a 2022 Point-in-Time count. This year, that number has jumped to 6,297, though the number of chronically homeless people in the Portland Metro region is declining.

Data in the latest report now comes from two sources: the medical examiner, and data from death certificates. That means people without a permanent address who die in hospitals or health care settings are also now recorded in the data. Previous reports contained only data from the medical examiner’s office.

The 2022 statistics are the first made available since the passage of Senate Bill 850, which requires mandatory reporting of a person’s housing status at death, making the latest Domicile Unknown report the most comprehensive to date.

The latest numbers tell the story of a system that doesn’t yet meet the needs of the thousands of people living unsheltered, or in unstable housing or temporary shelters. They also shine a light on the tragic reality most homeless residents face: a likelihood of death that far exceeds that of a healthy, housed person.

Kaia Sand, executive director of nonprofit Street Roots, which collaborates with the city and county’s Joint Office of Homeless Services (JOHS) on the annual report, said the deaths deserve pause and reflection.

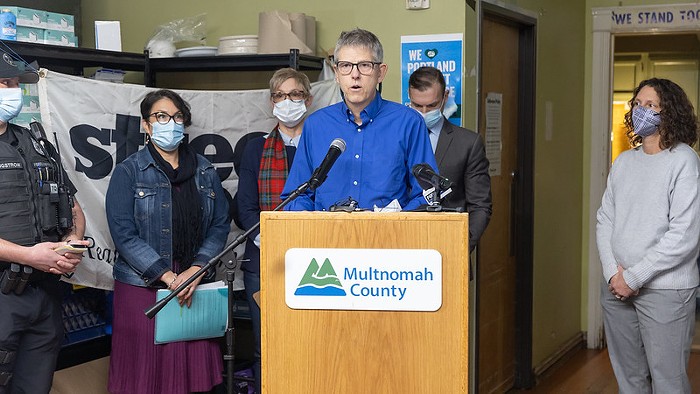

“I think it’s really important for us to pause with the gravity of this information and really recognize that it’s a collective grief,” Sand said Wednesday during a press conference about the report. “It’s an indictment on an entire nation that has a deeply unequal, [and] a frayed, if not missing, social safety net.”

According to the report, the county’s homeless population was nearly 45 times more likely to die from a traffic-related injury, 37 times more likely to die from a drug overdose, about 32 times more likely to die from homicide, 18 times more likely to die by suicide, three times more likely to die from heart disease, and three times more likely to die from COVID-19 compared to the general population of the county. The report’s authors also note unhoused people were about five-and-a-half times more likely to die from any cause than the general population.

The average age at death for those who died homeless in 2022 was just 49, which the report’s authors note is 30 years lower than the average U.S. life expectancy of 78.

“These are preventable deaths,” Dr. Paul Lewis, the former health officer for Multnomah County, who helped launch the Domicile Unknown report at the behest of Street Roots over a decade ago.

Overdose was most common cause of death

Of those who died, a staggering 46 percent died of unintentional injury, the vast majority of which were drug overdose deaths. In all, 123 homeless people died from an overdose last year, with 63 percent involving a combination of opioids and psychostimulants, like fentanyl used with methamphetamine. Another 14 unhoused died from traffic crashes. Many were pedestrians hit by cars.

Without consistent access to medical care, 80 people died due to health issues like heart disease, flu, liver disease, cancer, COVID-19, and stroke. The vast majority (32) of those deaths due to disease or illness were related to heart disease.

The next most common cause of death among the county’s homeless population was homicide, accounting for the loss of 25 lives, mostly due to gunfire.

Dr. Lewis noted unhoused people are at a risk of homicide that is more than 30 times higher than the general population.

"It’s a very, very traumatizing experience to read about the folks who died under these circumstances, often without shelter, companionship, etcetera," Dr. Lewis said. "Certainly not the way any of us hope are our final days."

What’s being done?

Since 2022, the city has opened additional Safe Rest Villages, and the first Temporary Alternative Shelter Site, with another one eyed in North Portland, pending site viability.

Currently, the governor’s office, Multnomah County commissioners, and city leaders are working to declare a 90-day fentanyl emergency on Portland’s streets, among other measures to improve central and downtown Portland’s vitality.

This week, Portland City Council approved a three-year contract extension with the county for coordination on homeless services, via JOHS. The extended partnership will use about $43.6 million in funds already allocated this budget cycle for homeless shelters, housing placement, supportive housing, homeless prevention services, and rental assistance for those at risk of homelessness.

While elected leaders hope increased shelter capacity, coupled with a crackdown on fentanyl will help reduce deaths, others point to a fundamental disconnect within local government.

Portland Commissioner Rene Gonzalez has spoken out against “enabling” the city’s homeless population on multiple occasions, in efforts to reduce resources and expenditures he deemed inefficient.

In February, shortly after taking office, Gonzalez announced he would prohibit Portland Street Response (PSR)–the city’s non-police emergency response team for people in crisis–from distributing tents or tarps to unhoused people the team engages with. The rationale? The commissioner, who is currently running for Portland mayor, claimed tents were leading to more people getting seriously injured by lighting fires or using portable heating devices inside them for warmth. Since then, PSR’s budget and supplies have been curtailed. Plans to expand the program to 24-hour service have been stalled.

This week, in a post acknowledging the Domicile Unknown report listing an uptick in homeless deaths, none of which were listed as being caused by fires or burns, Gonzalez again championed his previous policy.

“Those experiencing homelessness are especially at risk for serious burns, often resulting in death,” Gonzalez claimed in a post on X, formerly called Twitter, citing one death among three fires stemming from homeless residents earlier in the week. Constituents responded by lambasting the commissioner’s previous policy decisions.

For others, a bottleneck in the distribution of essential supplies for the region’s unhoused population has led to frustration.

Marie Tyvoll coordinates with volunteer homeless aid groups around the city. She says since JOHS scaled back the frequency and list of recipients at its homeless supply distribution center, it’s been difficult for smaller, volunteer-based groups to deliver help.

Last year, JOHS moved to a monthly distribution schedule, meaning fewer essential items like sleeping bags and hygiene items were made available, and less frequently. In 2021, JOHS began limiting supply distribution to only established nonprofits with tax-exempt status.

But in a city with a connected, active grassroots volunteer network that’s often able to reach unserved people, Tyvoll says those small, less formal groups are a lifeline for residents living unsheltered.

“Those deaths are in-part a direct result in many cases of JOHS not going back to weekly supply pick-ups for community members,” Tyvoll insists. “JOHS is shutting out an enormous community effort to keep people from dying by not distributing adequate supplies. We are trying to keep people alive, but we can’t do that with only five sleeping bags and tents a month.”

Peter Tiso is a supply center coordinator for JOHS. Tiso acknowledged the agency has a lengthy waitlist, but said JOHS is working to make the waitlist more efficient and equitable, with fewer funds at its disposal than in 2020 and 2021, when temporary COVID dollars allowed more supplies to be distributed.

“We have a number of groups on our waitlists who would like to be included,” Tiso told the Mercury. “We’ve been digging into, what does our budget look like, what can we afford to do and how can we basically ramp up to fill the need we're seeing and use the capacity we have to distribute supplies most equitably?”

Tiso noted that during extreme weather, JOHS will often relax its distribution guidelines and allow informal volunteer groups to pick up and distribute severe weather supplies.