I HAVE a close friend whose little brother—let's call him Chris—had a particularly tumultuous time growing up. Chris' teenage years were marked by teetering struggle, a suffocating wash of anxiety, depression, inadequacy, and rattling outbursts of rabid mania. During high school he tried to kill himself twice.

Chris eventually got a handle on life. He's since become a counselor for kids in similar spots. And while there were many other significant factors in his growth, Chris found solace in music, especially in Andrew W.K., who at the time had just released I Get Wet.

For Chris, the record was eye opening. Behind the intriguing, bloody, now-iconic cover explodes a smashing, unrelenting, life-affirming party where shredded notes and rapid-fire anthems slam together like 10-ton bombs of sweat-soaked confetti. Chris had always liked punk, but this was different: a celebration of self and community wholly devoid of nihilism, vindictive middle fingers, or self-loathing. Finally Chris had a modern diagram in which all those excess energies could be channeled in service of both good and fun.

Growing up in Michigan, Andrew Wilkes Krier also wrestled with his place as a teenager. "I had a lot of anger and a lot of just dark feelings and problems very similar to what a lot of people of that age would go through," Andrew W.K. says. "I had my own runs with seeing a child psychologist and getting in trouble for crimes and things like that. But that's when I found a way to direct all that into something hopefully more light rather than dark. You've just got to find what you're meant to do."

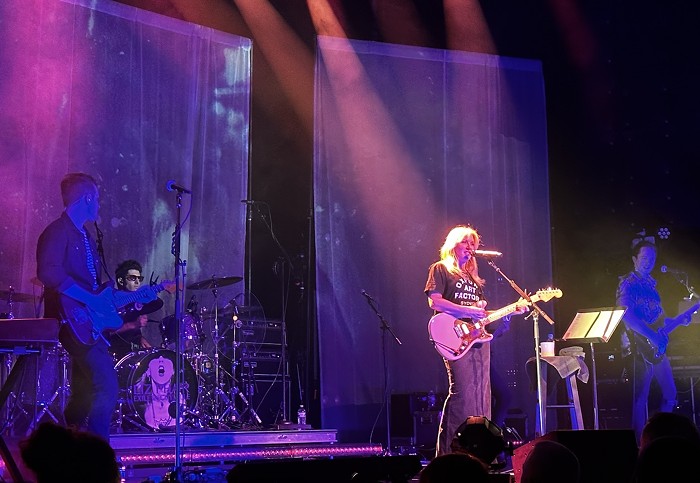

While this outpouring of ecstatic positivity informed 2001's I Get Wet—which W.K. performs in full on this current tour—it was magnified by the response. "Then," W.K. says, "the conversation began." What could've been disposed of as well-crafted, pounding, but seemingly vapid pop grew into an all-encompassing ethic. "Party Hard" became a legitimate lifestyle, as much an outlet for teenage angst as a way to stay young.

Since then, W.K. has become as much a guru as a musician or entertainer. While contractual issues limited his ability to release records and tour for the latter half of the '00s, W.K. remained irrepressible. Concerned more with message than medium, he hosted a TV show, gave lectures, and opened a rock club, all underneath the flipped-out umbrella of partying. "The whole point," he says, "is to make people feel exciting, enthusiastic, and to make people feel joy and powerful." It's about a lust for life, not so much drugs and alcohol.

"The only wrong way to party is to tell other people how to party," he says, sounding much like one of the many "party tips" offered on his Twitter feed. "The point of all this work is to unite the human race, really, through the power of music, the joy of partying and celebrations, you know, liberating the human spirit. The more I work on that mission and work toward it, the greater that work reveals itself to be." Still, W.K. recoils from self-aggrandizing, insisting that people—like Chris—who may find something in his work are doing the most important parts themselves.

"I'm just a person who's trying to stay in a good mood just as much as anybody," W.K. says. "And that was a lot of motivation to sign up for this: I thought it would make me less depressed, and it did. So it's just tremendous when it works for other people as well."