It's generally agreed that American black culture has been endlessly pilfered by white musicians—jazz, rhythm and blues, and rap have each taken their turns being appropriated, exhumed, and bastardized by whites. Of course, this literal-minded outlook ignores the give-and-take of ideas that's attendant with all cultural exchange, but although it's a broad simplification, it's proven to be a durable and surprisingly common pattern in the history of American music. So when a quartet of black South Africans reclaims that whitest of white genres—progressive rock, long the bastion of pimply tech-heads and doughy shut-ins—the predominately Caucasian world of indie rock sits up and takes notice.

Of course, it's not the first time a black artist has entered the arena of "white" rock—to name just a handful, Jimi Hendrix, Living Colour, and most recently TV on the Radio have each had their turn at redefining the black "role" in rock music, as if such a thing needed to have set parameters. But BLK JKS aren't African American; they are African, and their ease at inhabiting the tricky bombast of prog proves not only the similarities between Anglo prog and African township, but also the futility of separating and pigeonholing different musical varieties.

"As children coming up in the kind of state that South Africa was before '94," says BLK JKS guitarist/vocalist Mpumi Mcata, "we were always very inquisitive and hungry for knowledge of life beyond our immediate space; so indeed, as much as the wonderful and oftentimes powerful sound of South African music—from traditional to urban—surrounded us, we soon fell into the arms of, say, Ms. Nina Simone, then found even more strength in Fela Kuti, and, when we were coming to, Public Enemy, Sonic Youth... most of this we had to dig for."

BLK JKS' debut full-length After Robots has almost too many influences to measure, with messy polyrhythms butting up against tightly constricted funk, and clean jazz chords augmented by metal shredding. It's a record that sounds dominated by musicianship rather than songwriting, and as a result can be flashy at times, but that's often in the record's favor. "Taxidermy" sounds like early Rush meets Os Mutantes, while songs like "Banna Ba Modimo" are perhaps more similar to the Mars Volta than to anything else on the American rock scene. There are also a couple missteps; the ballad "Standby" wants to soar but feels awkward and gloppy, while "Skeleton" is an uneasy mixture of metal and reggae.

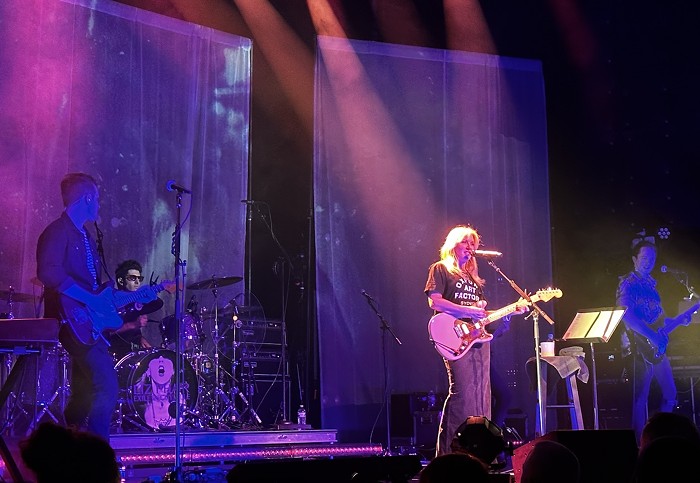

After Robots, out on Secretly Canadian, was recorded in their label's home (and the college town) of Bloomington, Indiana, and produced by Brandon Curtis of New York space rock band Secret Machines—a pedigree far removed from BLK JKS' Johannesburg home. The band's reputation is still largely based on their live show, which showcases both their American influences and their inherent African musicality. I ask Mcata if he's found that most of BLK JKS' audience in America is white.

"It's maybe because... most of America is white?" he responds. "No, we haven't really experienced it that way; spending most of our time in Brooklyn, the situation is pretty well mixed and balanced." In the meantime, he says, BLK JKS aren't allowing race, or anything else, to define their audience. "We'll just be taking this here soul food to as many people as we can all over the world and see where that puts us."