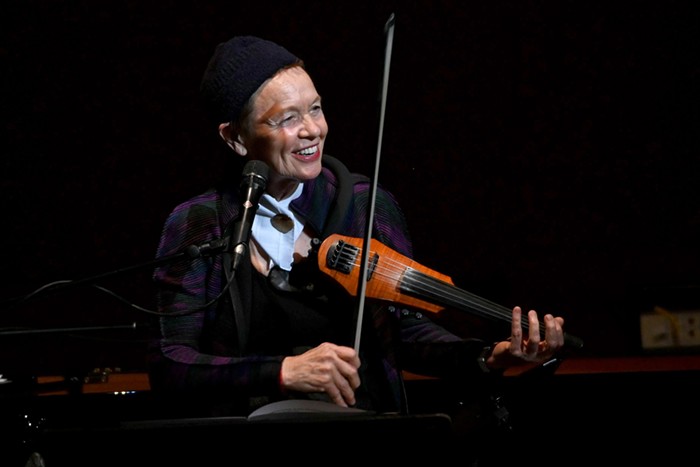

KRISTIN HERSH sums up her relationship with music like this: "It was beautiful, then it was a monster. Then it was a beautiful monster."

The 47-year-old leader of the long-running, ever-mercurial Throwing Muses is speaking in metaphors, but just barely. Hersh spent the better part of her life nearly possessed by sound. After being hit by a car on her bike at age 16 and suffering a double concussion, she began to be, as Pitchfork writer Katherine St. Asaph put it, "accosted by songs." Suffering from a strange form of dissociative identity disorder, Hersh would have fully formed tunes play on repeat in her brain, not letting up until she performed them.

It sounds like an ideal problem for a musician to have, but for Hersh, it was torture. And even though it was key to helping the Muses win critical acclaim and a sturdy fanbase, Hersh spent years searching for a solution.

She eventually found it in 2012, with a therapy called "eye movement desensitization and reprocessing" (EMDR), a process that involved focusing on the trauma of the accident while using external stimuli—a flashing light and vibrating electrodes—to help recalibrate the synapses in the brain. Effectively, the memory faded into the distance, and with it, the nonstop noise in her head finally came to an end.

Thankfully, it didn't mean the end of her 30-plus-year career writing songs. Instead, Hersh started building new creative muscles to push herself and her band forward.

"I sense songs and know what's right and beautiful for them," she says from her home in New Orleans. "Or what's ugly and fake, and I let them write themselves. But the music is no longer only sound, as odd as that seems. It's more like a will that I reflect in sound."

What that means for Throwing Muses is that, more than ever before, the trio of Hersh, bassist Bernard Georges, and drummer Dave Narcizo have connected the band's early, more barbed musical style with the cleaner punch of later albums like 1995's University and their self-titled 2003 effort.

Purgatory/Paradise, released last year, is a masterful work, sometimes placid but mostly roiling. Songs stop and start seemingly of their own free will; others adjust their tempos midway through. All are punctuated by Hersh's hard guitar strumming and the cracked glass of her vocals.

The album also offers Throwing Muses fans a glimpse at the four years it took to capture it on tape. A handful of songs are presented in their raw demo state, with the finished version appearing elsewhere on the album. And the music comes packaged with a book of essays and lyrics, complete with download options to retrieve the band's commentary on all the tracks.

It's indicative of the way in which our collective connection to recorded music has changed—something Hersh has been examining for years. She and Muses' manager Billy O'Connell helped found the now-Portland-based open-source nonprofit CASH Music, which offers tools for artists and bands to cut out the middlemen to get their tunes to the people. And she's maintained a subscription service that lets fans hear new songs as she churns them out.

"We aren't going to make any money or get famous," Hersh says, "so we have the freedom to work as little losers in the corner, which allows us to feel un-self-conscious."