According to the Portland Police Bureau (PPB), Quanice Hayes died because he had a gun.

“There was no doubt in my mind he had a gun,” PPB Officer Andrew Hearst told a Multnomah County grand jury in March of 2017. A month earlier, Hearst had fired three bullets at Hayes, leaving the 17-year-old African American dead. “I believed that he was going to pull that gun on us. And to defend myself and my coworkers, I knew I needed to fire my weapon.''

Now, nearly two years after Hayes’ death, a group of independent investigators say this reason alone wasn’t enough to justify a police officer’s use of lethal force.

According to an investigative report released Friday morning by the Office of Independent Review (OIR) Group, the four PPB officers who intercepted Hayes—after he committed a series of small-scale robberies while using a fake gun—should have better coordinated the orders they were yelling at Hayes, better protected themselves from anticipated gunfire, and slowed down their entire response to better calculate their actions.

OIR’s analysts found that PPB did not calculate these crucial factors—which could have greatly changed the outcome of the early morning encounter—into their follow-up review of the incident.

“Instead,” the report concludes, “[PPB] reached the fatalistic conclusion that Mr. Hayes’ actions drove the outcome.”

The report is clear: PPB’s process of reviewing fatal officer shootings does not adequately take into account potential officer errors in scenarios where it is assumed a civilian has a weapon

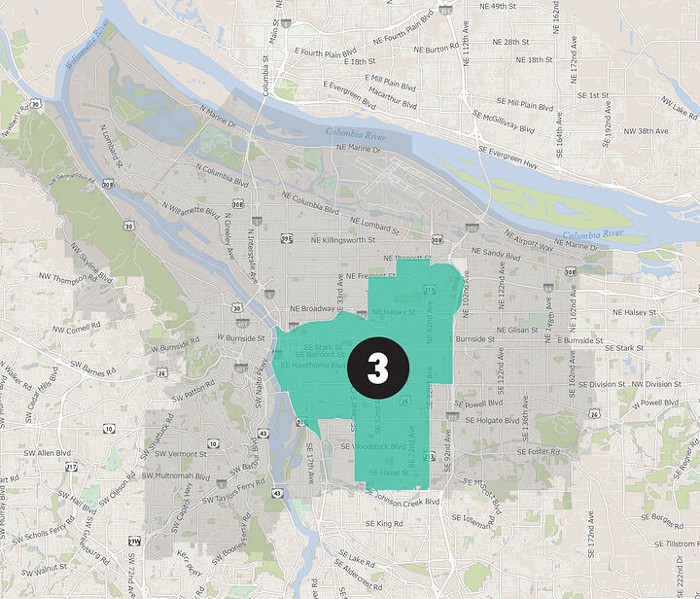

On February 9, 2017, Hayes was stopped by police in an alcove between a Northeast Portland house and a detached garage after a number of people called police reporting theft by a man with a gun who matched Hayes’ description.

Hoping to take Hayes into custody, officers directed him to exit the alcove—but, as OIR’s consultants note, there was little order to the process. According to the officers’ grand jury testimony, Hayes was told to “keep his hands up” and “crawl forward,” but cops later recalled Hayes telling them that he couldn’t do both at the same time. Multiple officers appeared to be yelling contradictory orders at Hayes.

“The statements from different witness officers painted a… confusing picture, with varying accounts of who was giving commands and when,” the OIR report reads.

That’s when Hayes reached down the front of his jeans—which officers say had been sagging—and Hearst shot Hayes three times with a semiautomatic rifle.

Only after Hearst shot Hayes did officers see a fake gun next to his body.

"[PPB] reached the fatalistic conclusion that Mr. Hayes’ actions drove the outcome.”

The consultants note that the confusion leading up to Hayes’ death underscores a “very significant issue.”

“If officers on scene have differing views of what the subject is supposed to be doing in order to demonstrate compliance, officers may develop different impressions of the subject’s level of cooperation and have correspondingly different reactions,” reads the OIR report. “And if the subject is confused about officers’ expectations, that creates another obvious set of problems.”

The PPB officers could have better coordinated their commands by simply “slowing the situation down,” note the consultants. This could have meant placing a cop car between the officers and Hayes, or instructing officers to retrieve and deploy bulletproof shields from the car—two tactics that would have “removed them from a vulnerable situation where they felt constrained to use deadly force.”

The report acknowledges that, at the time, officers had been chasing Hayes for several hours, and were probably eager to get him into custody. That may have rushed the officers’ decision-making processes.

“Upon discovering Mr. Hayes crouched in the alcove, officers almost immediately began giving him commands to crawl out,” the consultants write. “An alternative would have been to hold Mr. Hayes at gunpoint in the alcove while conferring with each other about a plan for taking him into custody.”

"It is imperative, consistent with the Bureau’s de-escalation policy, to conduct a more exacting review.”

The PPB review process that followed the 2017 shooting “did not sufficiently address these critical issues,” the OIR Group concludes. “It is imperative, consistent with the Bureau’s de-escalation policy, to conduct a more exacting review.”

The OIR report isn’t limited to Hayes’ death—it includes analysis on nine incidents over the past five years in which a Portland police officer shot a member of the public, and it offers no fewer than 40 recommendations for PPB to consider based on how the bureau handled and responded to each shooting. But the 132-page report pays particular attention to Hayes’ case, due to the considerable, long-lasting impact that the police shooting of a Black teen left on the Portland community.

The report acknowledges Portland’s history of racial inequality and displacement among its African American population.

“That long history of injustice understandably frames the public analysis of cases like the Hayes shooting,” the report reads. “This deep-seated distrust undermines confidence in… findings that excuse officers while providing neither consolation nor satisfaction to frustrated observers.”

The consultants leave PPB with a piece of advice: Don’t brush off valid criticisms of police shootings that leave African American Portlanders dead.

“Perhaps the best response police agencies can provide is to endeavor to build a reservoir of goodwill through honest dialogue, receptivity to feedback, [and] transparency,” the report reads.

"This deep-seated distrust undermines confidence in… findings that excuse officers while providing neither consolation nor satisfaction to frustrated observers."

The OIR’s recommendation couldn’t come at a more critical time.

Next week, Portland City Council will reconsider the 2017 firing of PPB officer who made a deeply racist remark after hearing public outcry related to Hayes’ death.

According to his termination letter, which was first made public Wednesday, Sergeant Gregg Lewis was fired after making a “joke” during a Central Precinct roll call that ended with the remark, “If you come across a Black person, just shoot them.”

Several of the 16 other officers present at roll call laughed nervously, the letter states. No one attempted to correct him. Lewis made this statement three days after Hayes’ was fatally shot by PPB Officer Andrew Hearst.

Now, with the the PPB’s union, the Portland Police Association (PPA), using the state’s arbitration system to legally challenge Lewis’ termination, the city is considering a settlement agreement that would erase Lewis’ termination, allowing him to retire with $100,000 worth of backpay. While Mayor Ted Wheeler acknowledges it’s an imperfect solution, he says the cost of losing an arbitration hearing against PPA—which could result in Lewis returning to PPB—is too high.

"If it was up to me, I’d say let's go to arbitration, let’s fight the good fight. Because even if we lose it, we send a very strong message that this is not acceptable.”

“If this goes to arbitration, we’re still going to pay the same amount… or maybe even more,” Wheeler said during a Wednesday city council hearing. “But what we lose in the arbitration process is that we make certain once and for all that this person will never work at PPB again.”

Commissioner Jo An Hardesty, however, isn’t satisfied.

At the Wednesday meeting, Hardesty said the two options presented by the city attorney “show that we are working within a broken system.”

“If it was up to me, I’d say let's go to arbitration, let’s fight the good fight,” said Hardesty, “because even if we lose it, we send a very strong message that this is not acceptable.”

It’s a message echoed in the pages of the OIR report.

In analyzing the response to Hayes’ death, consultants note that rebuilding trust between Portland’s Black community and the police will require “demonstrable willingness to evolve and improve.”

“Such efforts cannot preclude the possibility of future controversial incidents,” it continues. “They can, however, enhance confidence in the legitimacy and appropriateness of the Bureau’s responses—both systemically and in terms of individual accountability.”