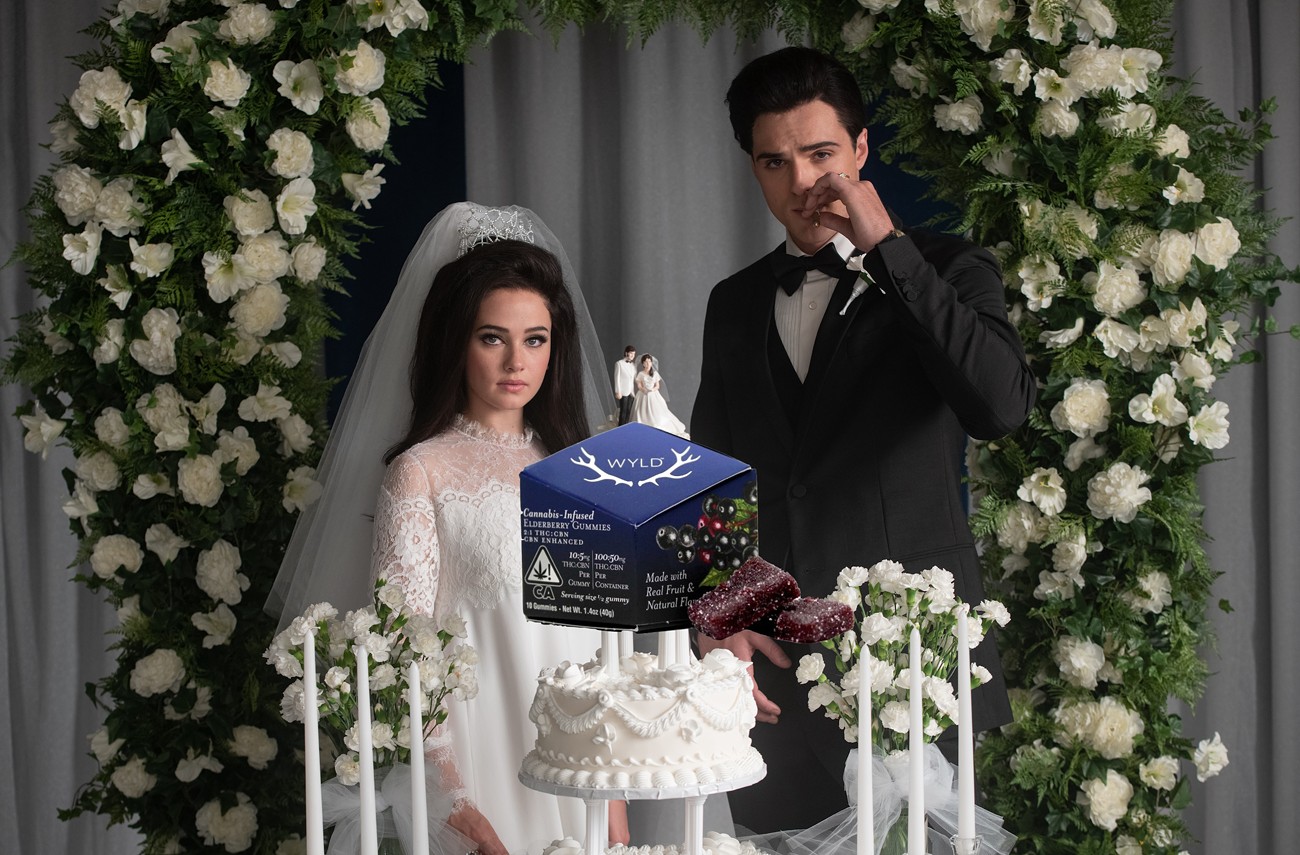

Priscilla, the new film by director Sofia Coppola, is atmospheric, expertly soundtracked, and lovely to watch. You don't have to be a razor sharp cinephile to see it represents 20+ years of Coppola's auteur style, woven into a soft focus portrait of young Priscilla Presley becoming a woman and the marriage that shaped her. You don't even have to be completely sober to see this—as it was all clear to me from the pillowy softness of an indica gummy high.

Over the years, Coppola has experimented with different cinematic tones, but she's best known for a narrative that wanders between wonder-filled haze and subdued melancholy. In a lightly toasted state, these transitions felt seamless, and I sunk into a visual bath of her particular approach to mise en scène.

[Dosage note: When I buy a box of 5 mg edibles, I cut them into thirds. I decide what I'm going to take, and I don't take more—I max out at around 3 mg. The cannabis industry's idea that a single serving should be 10 mg is bonkers—when it comes to edibles, less is more.]

With her first film, the 1999 Virgin Suicides, Coppola established a reputation as a stuff director. The overflowing vanity dresser of the five Lisbon sisters spoke loudly of young girls sharing an intimate space, forced into a stuffy codependence. Priscilla still works in Coppola's stuff oeuvre, but instead we watch Priscilla (Cailee Spaeny) unpack her makeup in Elvis' Graceland home after she moves in with him at age 17. Her lipstick seems to echo as she carefully sets it down. She is alone, in the great, grand place—playing at womanhood.

Montages of objects parade before the audience, signifying both the passage of and where we are in time. Coppola's missteps in Marie Antionette—another stuff-filled film about a woman growing up in a luxurious, but stifling environment—land here. It's not hard to imagine the director drawing from her own life, as the only daughter of massively influential director Francis Ford Coppola. Critics have called her films surface over substance, but in Coppola's view, surface is all that you can know. To suppose substance, or a view deeper into the subject, is pure hubris.

A downside to taking an edible before you see Priscilla is you can't know for sure if your version of the film is what everyone else experienced. And sure, you can't know that in general. If you love to argue, this could prove a great asset, as you will have plenty of things you remember slightly differently. For instance, there's at least one scene—where Elvis (a towering, complicated portrayal from Jacob Elordi) plays piano and sings "Hound Dog." Although pre-release coverage of the film touted no actual music from Elvis licensed for the film, it seemed like Elordi was overdubbed with the voice of another singer.

The person who saw the film with me claims this scene never even happened.

Unreliable narrators find themselves in excellent company at Priscilla. Even as Coppola weathers complaints about her nuanced portrait of the King of Rock and Roll, it's undeniable that she softened the source material of Priscilla Presley's 1985 memoir Elvis and Me, which was likely similarly softened by the author herself. Elordi's Elvis comes off as towering and manipulative, but a lot better than he could have, all things considered.

In this way, Coppola's portrait of the pair feels like an old Polaroid: It captures the moment, but with a soft focus glamor that presents everyone in an appealing light. It's a brief vision—a kind of truth—of a girl's dream and a woman waking up from it.

Priscilla is currently playing in wide release.